Minor Crimes, Major Consequences

Arrest as a Revenue-Driving Strategy — An Examination of Failure-To-Pay Arrest Warrants

Arzu Singh

May 28, 2024

Ashley W., a single mother of two young children working full-time and living below the poverty line in Austin, Texas, was washing her car at the park when she was arrested for unpaid traffic tickets. She did not even know she had an arrest warrant for her nonpayment. Despite being frantic about leaving her children, she was taken to the local jail where she was not given an opportunity to make any calls. She was unable to tell her boss she would be gone longer than expected, tell her landlord she would be late with rent, or arrange childcare for her children. Daniel M., a 23-year-old plumber and father of two, was arrested for unpaid traffic tickets, booked into jail, and not told how long he would be detained. He was unable to take his daughter to her first day of school, and his family’s home was robbed while he was in jail. Michael C. received five traffic tickets from Waco, Texas over a decade ago and has been to jail more than 20 times for those tickets. He still owes thousands of dollars due to all the fines and fees that have compounded over time. Lionel E. was arrested on a warrant for owing a total of $1,209 from three unpaid traffic tickets. While in jail, he experienced a seizure and by the time EMT got to the cell, he had passed away. Lionel was 23 years old.

Like millions of other Americans, Ashley, Daniel, Michael, and Lionel’s lives have been deeply impacted by the insidious American misdemeanor system that operates quietly but relentlessly in the shadows of the criminal legal system. Because society considers misdemeanor offenses––like traffic violations, jaywalking, petty theft––“minor,” these cases receive negligible public attention, legal resources, or scrutiny as to whether defendants are afforded due process of law. But these fine-only offenses nonetheless have profound consequences on individuals’ lives, especially when people are unable to pay the fines imposed by the courts.

Over the past few decades, state and local governments have increased the scale and magnitude of fines and fees imposed for misdemeanor offenses, such as traffic violations and “quality of life” crimes (which can include things as minor as biking on the sidewalk, being in a park after closing, “loitering,” and more). Because low-income communities of color are disproportionately policed, both on the roads as well as in their communities, this system of fees and fines creates “a regressive system of taxation… now entrenched in virtually every state, and in municipalities large and small across the country.”

These monetary sanctions on people with limited financial means and communities of color effectively creates a two-tiered system of justice where those who cannot pay are trapped in a cycle of poverty and punishment. Misdemeanor fees and fines are an example of what some scholars have termed the “criminalization of poverty”: the idea that the American criminal legal system punishes people simply for being poor. This racially discriminatory and profit-driven approach to law enforcement is enabled by the collaborative efforts of local government, police, and courts.

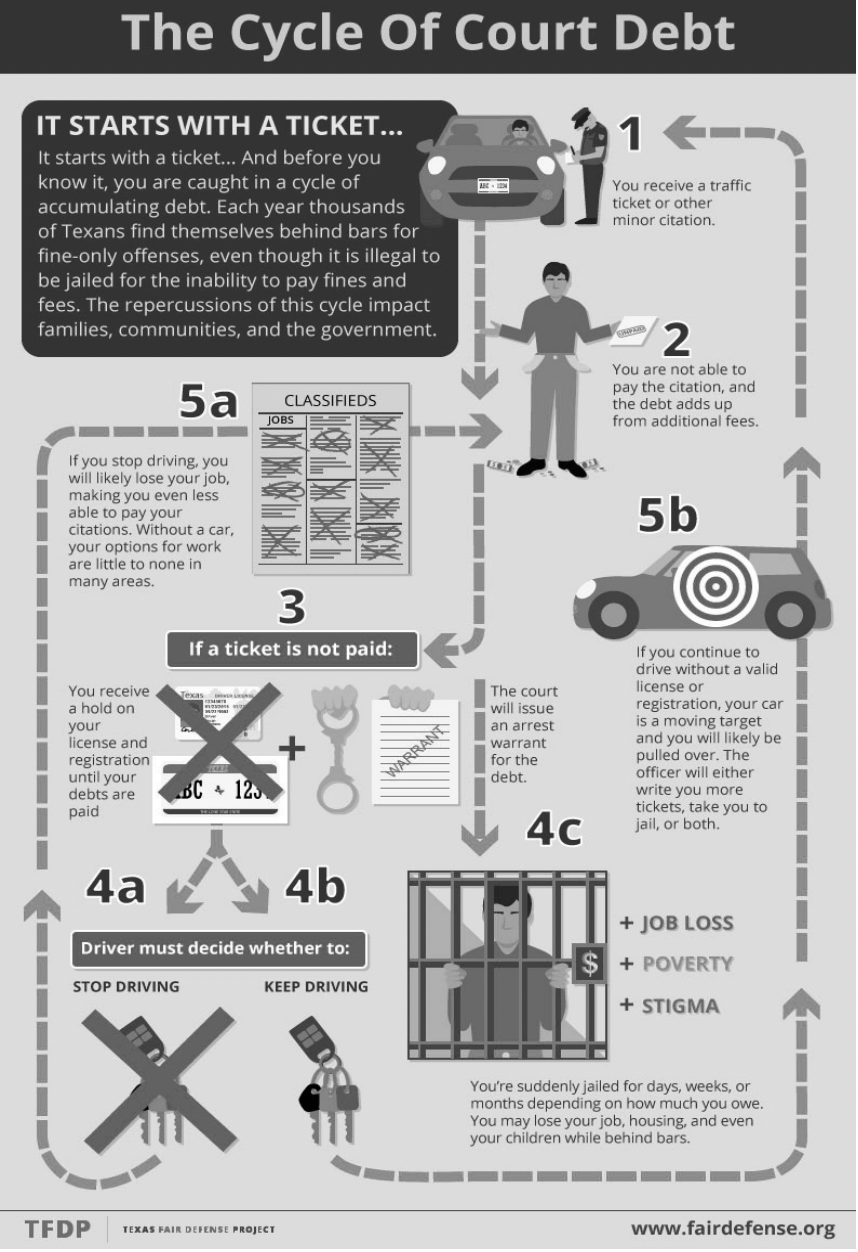

When individuals cannot pay their fees and fines, also called “legal financial obligations” (LFOs), courts employ various punitive tools of the state to coerce payment or punish people for nonpayment––namely, arrest warrants and incarceration. Fine-only offenses can lead to arrest warrants in two situations. The first, known as a “failure-to-appear” warrant, can be issued when a person fails to show up for a court date. The second, known as a “failure-to-pay” warrant or capias warrant, can be issued when a person fails to satisfy fines or fees. Ironically, these warrants often come with their own additional fees.

In Texas, when a court issues an arrest warrant, it adds a $50 warrant fee to the individual’s original ticket. In Oklahoma, it adds a $250 dollar warrant fee––equal to the original fine owed by the average Oklahoma debtor. When someone is arrested on a warrant for a fine-only offense, she is typically booked into the local county or city jail until she is brought in front of a judge who will assess her “ability to pay” the fines. Typically, imprisonment is treated as a substitute for repayment where court debtors earn a certain amount of credit—often $50 to $100 a day for each day they sit in jail.

Source: Texas Appleseed/Fair Defense

The scale of capias warrants being issued is tremendous. Between 2012 and the end of 2018, for example, Texas municipal courts issued 4.9 million capias warrants. In 2015 alone, Texas municipal courts issued approximately 688,000 capias warrants in fine-only misdemeanor cases. This means that millions of Texans are living with an active warrant for their arrest and are subject to being booked in jail at any time for fine-only offenses.

The resulting imprisonment from these warrants is substantial, too. A 2023 study conducted by scholars at the University of Texas Southwestern found that between 2005 and 2018 approximately 38,000 residents of Texas and around 8,000 residents of Wisconsin were jailed each year on failure-to-pay warrants. Although half of those arrested were jailed for a day or less, the “average” individual spent 2.1 days in jail in Texas and 6.2 days in jail in Wisconsin. In a 2015 survey of 95 New York public defenders and defense attorneys, 79% of attorneys who had represented defendants arraigned on warrants for unpaid fines said that those defendants spent time in jail.

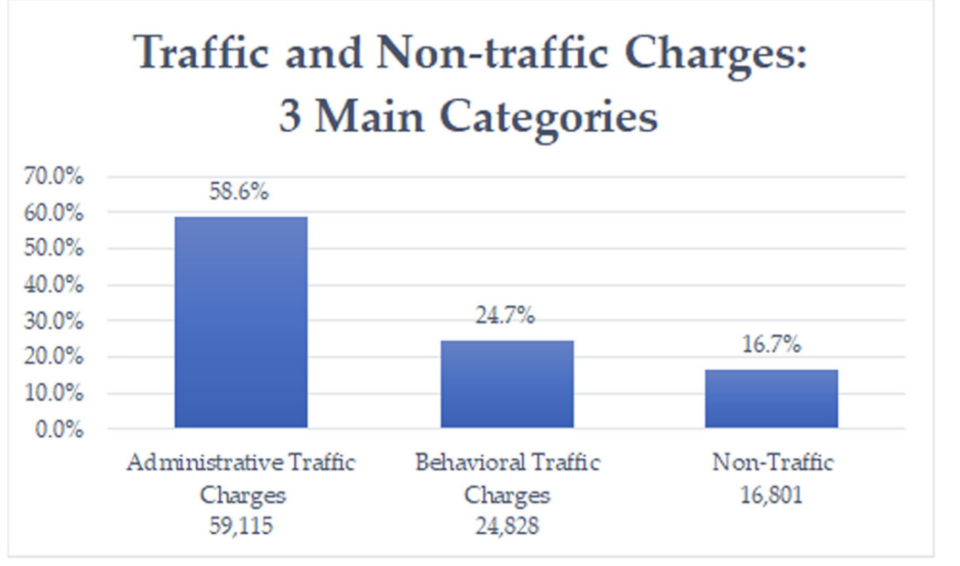

The Façade of “Public Safety”: Predatory Cities

Most of these paid fines and fees come, perhaps surprisingly, from traffic offenses. In Texas and Oklahoma, for example, 64% of associated charges for failure-to-pay warrants issued were traffic-related. A study that looked even more granularly into arrest warrants in Nevada found that most traffic violations that led to warrants were not “moving” violations, but were administrative violations, such as the inability to pay for insurance, driver’s licenses, or vehicle registration. This data tells the story that courts do not: enhancing public safety is not the motivation behind these fines, even those related to traffic offenses.

Source: Costs and Consequences of Traffic Fines and Fees: A Case Study of Open Warrants in Las Vegas, Nevada

What is driving these fines and their corresponding capias warrants, then? In large part, generating funds for local police systems and courts. In the first decade of the 21st century, there were nationwide cuts to court funding due to the macroeconomic conditions of the 2008 recession. Legal publications from these years noted that “[a]cross the country, courts are being asked to do more with less,” “[t]he current fiscal crisis is provoking budget reductions so deep they threaten the basic mission of state courts,” and “[t]he courts of our country are in crisis.” Courts, suddenly hollowed of their funds, were asked to function more like profit-producing corporations than institutions serving the public.

Around that time, the National Center for State Courts generated a comprehensive list of “revenue generation strategies, including enhanced collection of uncollected fines, penalties and surcharges.” Courts rapidly increased their reliance on monetary sanctions as a source of financial support, with little attention to the disparate impact these policies would have on low-income communities.

Through these extractive monetary sanctions, many cities have become “predatory cities”: urban areas where public officials systematically take property from residents and transfer it to public coffers, in violation of residents’ rights.

Through these extractive monetary sanctions, many cities have become “predatory cities”: urban areas where public officials systematically take property from residents and transfer it to public coffers, in violation of residents’ rights. These cities are charging low-level offenders to extract fines and fees, in order to turn the money around to fund the very courts and jails that processed the offenders. Even though Texas law technically prohibits requiring a judge to collect a certain amount of money through fees and fines, many judges still feel pressure to raise revenue. One anonymous Texas judge said a city council member repeatedly threatened to replace her if she did not meet projected revenue goals; another Texas judge resigned because of the constant pressure from city officials to collect on speeding tickets and called the city’s municipal court a “cash cow.”

Are Capias Warrants Even Constitutional?: Doctrinal Background

A series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1970s created the doctrinal backdrop that, while creating some “limitations,” has protected the practice of arrests based on unpaid monetary sanctions.

In 1970, in Williams v. Illinois, Willie Williams was convicted of petty theft and received the maximum sentence of one year imprisonment and a $500 fine. But because Williams could not afford to pay the monetary sanctions, the court ordered him to remain in jail to “work off” the debt at the rate of $5 per day—more than 100 days beyond the maximum period of confinement for the crime itself. The Supreme Court held that this violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, as the imprisonment resulted in “impermissible discrimination that rest[ed] on ability to pay.”

A few years later, in Tate v Short, the Court reiterated that courts could not convert traffic violation fines into jail time for indigent defendants without the resources to pay. A decade later, in Bearden v. Georgia, the Court held if an individual cannot pay despite making genuine efforts, she cannot be imprisoned if there are alternative measures adequate to meet the state’s interests. The Court held that “a sentencing court must inquire into the reasons for the failure to pay” and first exhaust all other methods to punish and deter criminal behavior short of incarcerating someone.

Together, Williams, Tate, and Bearden create a clear rule: the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits imprisonment for failure to pay monetary sanctions without a prior hearing inquiring into the reasons for the failure to pay and considering alternatives to imprisonment where the failure to pay is not willful. What these decisions don’t prohibit, however, is issuing arrest warrants for individuals who have not paid their fines and jailing those individuals until they receive an “ability to pay” hearing. Nor do these cases address what equitable methodologies should be employed in an “ability to pay” hearing.

Injustice in Practice: “Ability-to-Pay” Hearing after a Capias Warrant Arrest

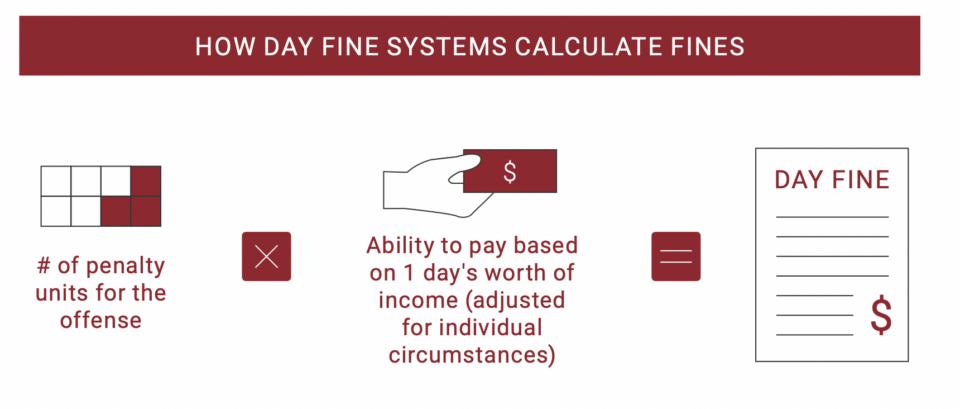

Court records reveal the egregious inadequacy of hearings that take place after arrest on a capias warrant. Judges often don’t inquire about income and financial dependents, the two questions most fundamental to ability to pay, and court documents for people committed to jail commonly indicate that they are unemployed or homeless. Sometimes courts use preprinted forms with no space to record the basis for their findings and without any indication of whether or not the person was able to pay.

Even when a judge formally evaluates a debtor’s ability to pay, the standards required to be deemed unable to pay are often impossible to meet. In New York, one defendant admitted that he had bought a pack of cigarettes in the time since the sentence was imposed and was found to be in willful violation of the fine requirement. Some judges require debtors to get the money from family members or “to use Temporary Aid to Needy Family checks, Social Security disability income, veterans’ benefits or other welfare checks to pay their court fees.” Judge Robert Swisher, a judge in Washington, explained that he made decisions based on his own personal perception of the debtor: “They come in wearing expensive jackets…or maybe a thousand dollars’ worth of tattoos on their arms. And they say, ‘I’m just living on handouts.’” If the debtor explains that the jacket or tattoos were a gift, he says they should have asked the giver for the cash to pay their court fees instead. The bottom line: most of these hearings fail to assess individuals’ “ability to pay” in any meaningful way.

Injustice in Practice: Racial Disparities in Capias Warrants

While “ability-to-pay” hearings are clearly fraught with injustice and discrimination, the process is deeply discriminatory in its earlier stages, too––including at the stage of capias warrant issuance. Data collection on failure-to-pay warrants is decentralized and alarmingly sparse. However, in all municipalities where data is available, the data tells a consistent, clear story: Black people are far more likely to have an arrest warrant issued for their failure to pay LFOs.

According to an investigation of the city of Ferguson conducted by the Department of Justice, Black individuals were at least 50% more likely to have their cases lead to an arrest warrant and accounted for 92% of cases in which an arrest warrant was issued by the Ferguson Municipal Court in 2013. The scale of warrants being issued was gargantuan: the city averaged three warrants per household; “fines and fees became almost-universal experiences for poor, black residents.”

According to Las Vegas Municipal Court open warrant data from 2012–2020, the individuals most commonly impacted by warrants were between the ages of 18 and 34 (47.1%), male (65.7%), from the poorest ZIP codes (58% from median income and below), and much more likely to be Black than any other ethnicity (44.7%). Similarly, in the city and county of San Francisco, Black residents make up 5.8% of the population but are 48.7% of the arrestees for failure-to-appear and failure-to-pay traffic court warrants.

![[F]law School Episode 12: The Body (S)camera](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/POOKKULAM_HERO-e1728232922783-640x427.jpg)