Nowhere to Hide: A World Without Privacy

How data mining and surveillance capitalism will impact reproductive rights in the post-Roe abortion landscape

Jessica Grubesic

June 12, 2023

In his 2013 dystopian novel The Circle, Dave Eggers follows Mae, an employee of the lightly-fictionalized Google-analogue from which the novel derives its title. The plot centers on the launch and rise of SeeChange, a network of wearable cameras that broadcast their users’ every move to their online followers in a bid to advance the values of The Circle, which include Orwellian proclamations such as “secrets are lies” and “privacy is theft.”

Though it may seem horrifying, The Circle is a pale imitation of today’s surveillance capitalism, in which Google, Facebook, and Microsoft have effectively created a SeeChange program sans cameras. The terrifying truth is that even constantly-worn, constantly-broadcasting cameras are inferior to the tools now at big tech’s disposal, which include but are not limited to wearable tech. Instead, companies like Google have mastered the collection and use of data to both track and predict our every move. All the while, big tech claims they are only acting in our best interest, making life easier for us, one digital assistant at a time.

Digital Privacy Rights in the Age of Surveillance Capitalism

In order to understand how tech companies use data practices are endangering abortion providers and those seeking care, it is important to review digital privacy rights (or the lack thereof). In the digital context, it boils down to third party doctrine: individuals who give information or data to third parties no longer have a reasonable expectation of privacy and therefore forfeit their Fourth Amendment rights to the information revealed. Third party doctrine is derived from two 1970s Supreme Court decisions, yet it is the backbone of modern digital privacy law. In effect, any information obtained or maintained by a third party is not protected under the Fourth Amendment and can be obtained through the company’s voluntary surrender or via mere subpoena.

As plaintiffs’ attorney Eli Wade-Scott put it, “big tech’s business model is complete surveillance.”

It is worrying enough that everything stored in our Google Drives and iClouds, every Tweet or Instagram post, every “private” message sent through an unencrypted app is unprotected. But the information we voluntarily put online makes up a miniscule amount of the data big tech companies actually maintain on each of us. As plaintiffs’ attorney Eli Wade-Scott put it, “big tech’s business model is complete surveillance.” In other words, we are in the age of surveillance capitalism, defined by Harvard Business School Professor emerita Shoshana Zuboff as, among other things, “[a] new economic order that claims human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction, and sales.”

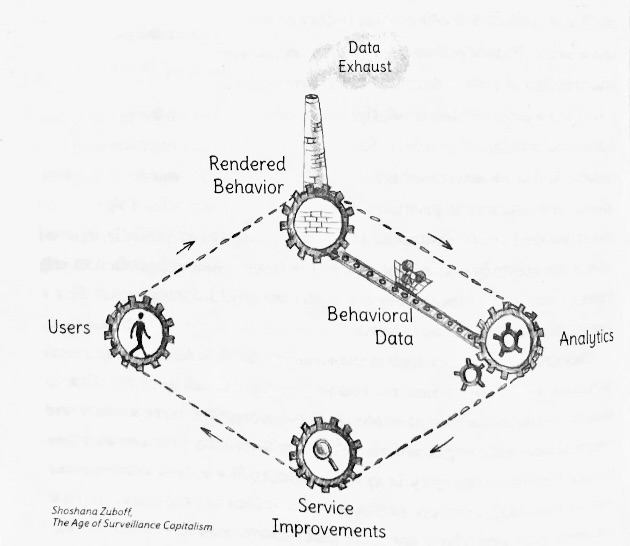

Before there was surveillance capitalism, there was what Zuboff calls the “behavioral value reinvestment cycle.”

Reproduced from Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism Figure 1, 70 (2019)

In the early days of Google search, Google’s algorithms learned from users’ search queries (including keywords, phrasing, spelling, punctuation, the amount of time spent on a page of search results and click rates for search results and ads) to generate more relevant and comprehensive search results. Google supported their work through licensing deals and revenue from sponsored ads linked to keywords chosen by advertisers.

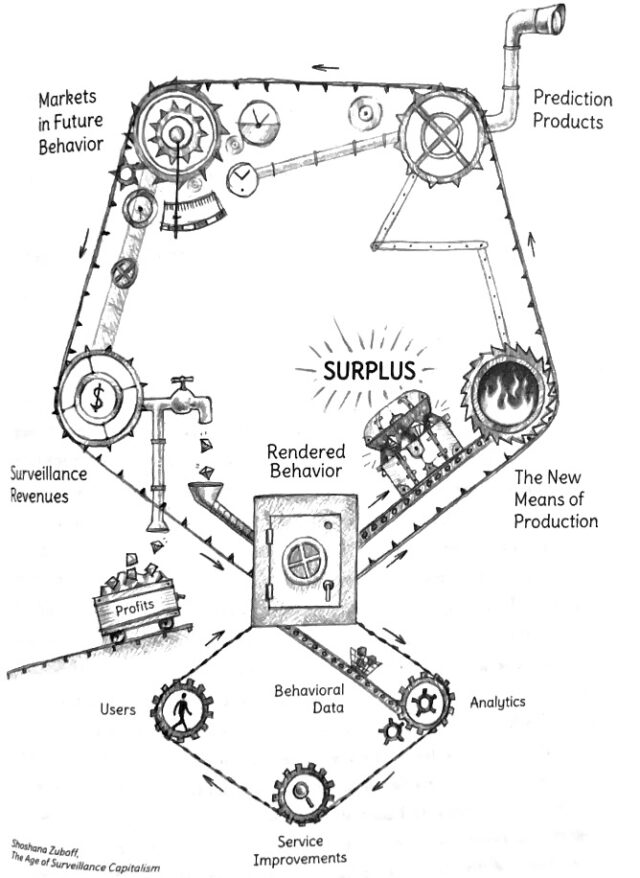

When the dot-com bubble burst, Google survived by innovating: they realized they could monetize the data gathered from their search engine by using it to target ads to individuals. Instead of allowing advertisers to choose keywords for their sponsored ads, Google would target ads to specific individuals based on user data gathered through Google search and refined into user profile information (UPI) by Google’s machine learning classifiers (or artificial intelligence). The data, so refined, becomes a predictor of behavior—including the likelihood a given user will click on an ad and purchase the corresponding product. Using targeted advertising, Google increased its revenues by 3,590% between 2000 and 2004.

Targeted ads proved enormously profitable and virtually every big tech company followed suit in implementing the practice. Because high prediction accuracy requires both a large quantity of data and a wide variety of data, big tech began scraping more and more of our data, using location data and smart devices to monitor not just our online behavior and friendships, but also where we go, who we spend time with, even what we say and how we say it. As our online and offline lives have become increasingly intertwined, tracking capabilities have increased. Now, we are tracked everywhere we go, by our phones, by other’s phones, by apps, by Wi-Fi networks, even by medical devices such as breathing machines used for sleep apnea, blood glucose monitors for diabetes, and apps used to track periods. As the world becomes ever-“smarter,” retaining any semblance of privacy grows further from our grasp.

Zuboff dubs the predictive signals derived from such data “behavioral surplus.” Where collateral data had previously been used to improve search engine performance in service to the user, behavioral surplus is now used in service of higher ad revenue, continued monopolization, and even behavioral modification.

Reproduced from Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism Figure 2, 97 (2019).

Everything from search terms and punctuation, to user location to purchases, to brain waves, is valuable. Google and other surveillance capitalists (for example, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft) are insatiable in the pursuit of digital and real-world data and the profits it can generate, making improvements to search engines and platforms not to serve their users, but to keep them coming back so that they will continue generating the data that serves as raw material for the true product: predictive capabilities sold in “behavioral futures markets.”

Because behavioral surplus is so valuable for precise ad targeting, engineers have made it virtually impossible to opt out, by making tracking systems unresponsive to users’ permission settings, making the product virtually nonfunctional if tracking is not enabled, or simply by ignoring opt outs and lying to consumers. State legislatures and attorneys general have fought back, settling a recent lawsuit against Google for $392 million. That amounts to a slap on the wrist, as Google’s annual revenue in 2021 was over 600 times as large as the settlement amount (and had grown by 41% since the previous year). As a result, companies like Google, Facebook, and Amazon are now capable of learning our daily routines and of applying that knowledge to predict and influence our behavior.

![[F]law School Episode 5: The Business of Boredom](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Reed_1-640x427.jpg)