Backed by what seemed like almost everyone, the body camera industry boomed. In 2014, President Barack Obama asked for $263 million in body camera and training funding as part of his plan to restore trust between communities and police ($75 million of which would go directly to outfitting police departments with body cameras), with an additional promise to purchase 50,000 body cameras for law enforcement agencies in three years. The Justice Department eventually handed out over $23 million in funding to over 70 law enforcement agencies for a body camera pilot program.

The President of the Washington, D.C. Police Foundation claimed that body cameras would become ubiquitous in the world of policing after Ferguson. He was right. By 2016, 80% of large police departments had acquired body cameras for officers. This movement to turn body cameras into a regular feature of policing was the “largest new investment in policing in a generation” and cost millions.

Body Cameras Help Police, Not Victims of Police Brutality

This generational investment hasn’t been all that. A recent ProPublica investigation uncovered that police have been keeping body camera footage to themselves, killing the accountability revolution in its cradle. Despite pouring millions to equip police with body cameras, policymakers failed to establish a robust control mechanism for the evidence that the cameras produced. Police departments were left to decide who could access the body camera recordings and how and if to release the recordings to the public. Departments often do not release video footage at all, even if they tout the cameras as transparency tools. For example, the NYPD often denied record requests of body camera footage, released edited videos, or falsely claimed that the footage did not exist.

And even when the footage is released, it paints a picture very favorable to police. Alec Karakatsanis, founder and Executive Director of Civil Rights Corps, notes that body camera footage is often shot from the officer’s chest. The outward-facing, lower angle and police movement and jostling of the camera makes the footage appear chaotic. “The perspective makes everything feel more urgent and more rushed.”

These chaotic videos make it easier to conclude that the police had no choice but to use force in the way they did. A New York Times article makes this point by comparing footage recorded by a body camera against that recorded by a bystander—in each of the comparisons, the body camera footage looks more chaotic and threatening than the bystander video. When determining whether or not an officer’s use of force was reasonable, chaotic body camera videos taken from an officer’s perspective will color the court’s interpretation of the event in favor of the officer. When we view video from someone’s perspective, “we tend to adopt an interpretation that favors that person,” a phenomenon known as “camera perspective bias.”

Some departments take advantage of this bias to use body camera video in a different way—as propaganda. Shakeer Rahman notes that, after shootings, the LAPD releases body camera footage as a highly edited, narrated, carefully produced video (just as the Fontana PD did with Mr. Kinard’s death). The videos, he says, are often misleadingly edited, leaving out key moments in favor of the most favorable views. It’s not disclosure—it’s propaganda.

Further, body cameras have not accomplished the policy goals of adjusting police behavior or leading to more accountability. A 2019 study in Criminology & Public Policy reviewed body camera literature and found that the use of body cameras did not have any statistically significant effects on officer behavior or citizen opinion of police. A Department of Justice review admitted that “[r]esearch does not necessarily support the effectiveness of body-worn cameras in achieving those desired outcomes.”

Some departments take advantage of this bias to use body camera video in a different way—as propaganda.

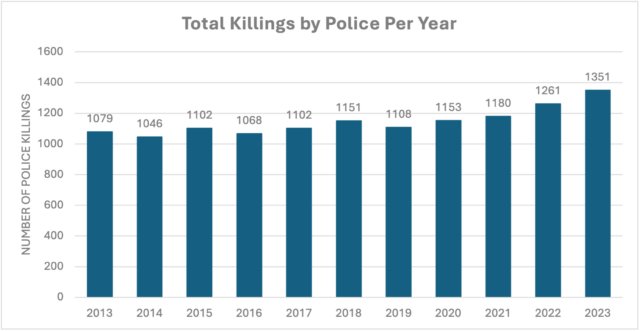

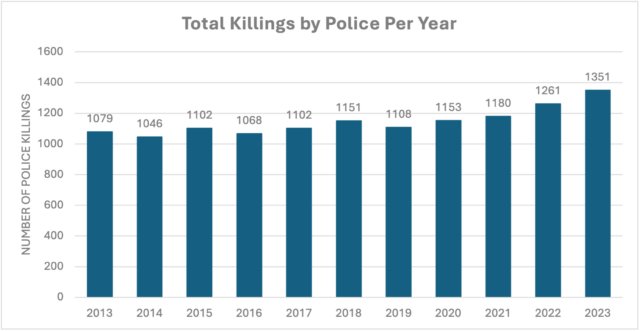

Nor have body cameras had any noticeable change on the total number of people killed by police—since their explosion in 2016, deaths by police have only risen. Even after George Floyd was murdered in 2020, police killings consistently rose. According to the data, body camera “accountability and transparency” have not affected the number of people the police kill.

Graph created by author, data sourced from Mapping Police Violence.

And yet, the government and law enforcement agencies continue to pour millions into this ineffective solution. In 2023, the Bureau of Justice Assistance (housed under the Justice Department) awarded 52 grants totaling over $20 million to local governments, housing authorities, and school districts under its “Body-Worn Camera Policy and Implementation Program to Support Law Enforcement Agencies.” The same program awarded $20 million to 35 law enforcement agencies in 2022.

Axon Manipulated a Police Brutality-Weary Public by Advertising Body Cameras as the Solution to Police Accountability and Transparency Issues

While the public was reeling from the death of Michael Brown, Axon stepped in to market body cameras as a technology that would record civilian-police interactions, making it easier to hold police accountable and increase police department transparency with the public.

A different spokesperson for Axon called Michael Brown’s death at the hands of police a “massive awareness campaign” for body cameras.

At the time, Rick Smith framed the problem as a distrust between communities and police and said that “[Axon] believe[s] wearable technology — like body-worn cameras—is the future for communities to relate to those entrusted to protect them.” He described Michael Brown’s death as a tipping point for the “concept of using wearable cameras to provide a foundation of transparency.” This was the same man, who, just two years ago, had described body cameras as a way to help reduce the amount police departments had to pay to settle civilian complaints about police brutality. Axon had changed its narrative.

A different spokesperson for Axon called Michael Brown’s death at the hands of police a “massive awareness campaign” for body cameras. The spokesperson acknowledged that Axon’s body cameras were not a panacea, but that they were “about as close as you can get right now.”

This was Axon tapping into America’s desire for an easy solution to the issue of racist and deadly policing. Seth Stoughton, a professor of law at the University of South Carolina claims that the country has a draw to quick, easy fixes—he calls it “silver-bullet syndrome.” Axon, it seems, knew what the country was thinking.

Investors also seemed to sense that Axon’s tides were turning, as Axon’s stock almost doubled in the four months after the shooting, to its highest point in years. In an earnings call just two months after the shooting, the company’s CEO, Rick Smith, said that Axon was feeling phenomenal.

Axon dominates the body camera market right now. It made $1.56 billion last year and expects to make between $1.88 and $1.94 billion this year. It controls the majority of the body camera market (with its closest competitor being Motorola), a market which is projected to grow to $7 billion by 2026. It’s total addressable market (meaning the revenue opportunity for a particular product) is a whopping $65 billion. As of 2022, it sells products to over 95% of state and local law enforcement agencies in the United States. Axon’s marketing strategy was a major part of its success, but so were its relationships with law enforcement and government and its lobbying efforts.

Axon cultivated relationships with police department and local government personnel. The company covered airfare and hotels for law enforcement personnel who spoke at Axon’s promotional conferences and hired recently retired chiefs as consultants (sometimes very soon after the company sold the chief’s police department its products). Axon has offered chiefs gifts. It paid the Memphis mayor’s campaign manager $800,000 at the same time it signed a $9.4 million body camera contract with the city. A lawsuit filed by a competitor outlined over 10 cities whose body camera contracts were directed by government officials who were financially tied to Axon. Some of Axon’s relationships with officials prompted investigations to ensure that ethics laws had not been violated. The company’s close relationship to police chiefs and other government officials is worrying and implicates Axon’s capture of all sorts of law enforcement agencies and municipal governments.

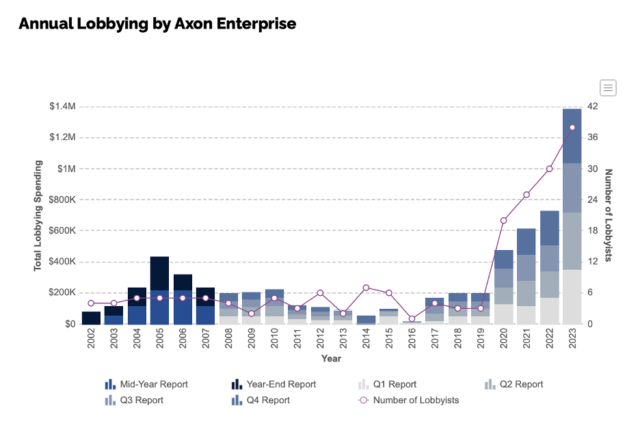

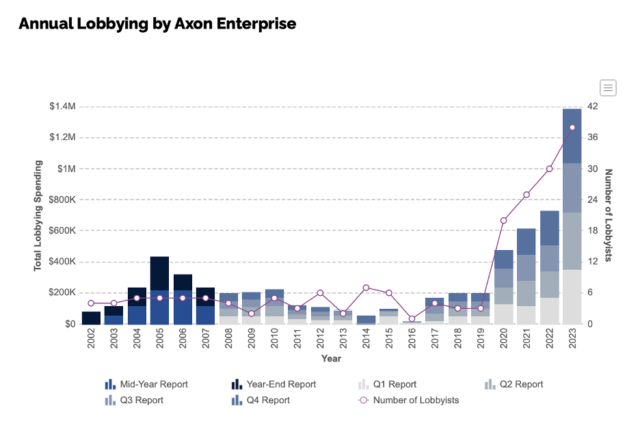

Axon also spends millions on lobbying the federal government. Axon more than doubled its lobbying efforts (in terms of dollars spent) between 2019 and 2020, likely in response to George Floyd’s murder and the renewed interest in police accountability and transparency that his death and subsequent Black Lives Matter protests sparked. And since then, Axon has only spent more and more.

Last year, the company spent about $1.4 million (about double what it spent in 2022) to lobby for various bills that proposed pouring more money into purchasing body cameras for law enforcement agencies. For example, much of the company’s lobbying energy went into the Law Enforcement Innovate to De-Escalate Act. Axon’s lobbyists advocated for the bill to include funding for body cameras and the accompanying evidence management tools. The company also lobbied for such funding to be included in the National Defense Authorization Act, Homeland Security appropriations, and Defense appropriations.

Behind all of this activity is the knowledge that body cameras are not working in the way that Axon advertises. Axon’s moonshot campaign acknowledged that police killings have risen in the past six years, years in which its cameras have been on the market and used by many agencies and departments. It had contracts with the Minneapolis Police Department (which employed George Floyd’s killer) and the Louisville Police Department (which employed Breonna Taylor’s killer) before the events of 2020. The world found out about George Floyd through video captured by Darnella Frazier, a witness to his death, not police body camera video. In Breonna Taylor’s case, the cops involved either were not wearing their body cameras at the time or did not turn them on. The inconclusive research regarding the effects of using body cameras is also publicly available.

And yet, Axon continues to advertise itself as a “force for good.” In a statement in response to George Floyd’s killing in 2020, Rick Smith made a moving promise: To build technology that “helps eradicate racism and excessive force in the justice system.” In its 2023 report, the company congratulated itself on “usher[ing] in greater potential for a less-lethal future,” “expanding Axon’s connected ecosystem to help save lives,” and “[m]aking the right things easier and the wrong things harder” through product development.

Axon is all-in on its branding strategy as a company that protects life. But it is, at its core, a weapons and law enforcement technology company. And its eyes are turning to the next great frontier of body cameras: expanding the surveillance state.

Body Cameras Strengthen the Surveillance State

In addition to not delivering on its promise of transparency and accountability for police, the body camera actually increases the power of the state to surveil poor communities and communities of color. Tying body cameras to police accountability has provided them a veneer of legitimacy. Where before, the public would have balked at body cameras’ ability to surveil us, now, we think of them as protecting us from police violence. We pour more money into this technology, which is then used to invade our privacy and collect evidence against us.

Body camera footage is evidence and has been used as such in the prosecution of private citizens, not just police officers. According to a 2016 study from George Mason University, nearly all (92.6%) prosecutors’ offices in jurisdictions that use body cameras used the evidence to prosecute citizens. According to the same study, almost two-thirds of prosecutors believed that body camera footage would be more helpful to prosecutors than the defense and “would improve prosecutor’s overall ability to prosecute cases.” Axon actively advertises its evidence platform to prosecutors as a way to simplify evidence sharing with law enforcement.

The body camera actually increases the power of the state to surveil poor communities and communities of color.

Body cameras are ubiquitous and mobile surveillance devices that record all sorts of public and private activity (including faces), which is then stored for years. Police enter and investigate private spaces often in response to calls. When they do so, their body cameras pick up video and audio of citizens engaging in private, domestic activity. Police also record the public spaces they routinely patrol (which are most often communities of color). This data is all collected and stored in places like Axon’s digital evidence management systems indefinitely. This footage can then be “algorithmically analyzed, converted into metadata, and stored in searchable databases.”

The rise of AI (which Axon is currently incorporating into the package of services it offers) and facial recognition technology dramatically increases the state’s surveillance capabilities. Perhaps sensing the amount of money to be made in making state surveillance easier, Axon recently acquired Fusus, an AI surveillance company whose product brings private and public security camera footage into one live feed. This footage can come from doorbell cameras, drones, fixed private security cameras, helicopters, police body cameras, and cameras in schools or churches. The product then adds AI to the cameras and allows them to detect vehicles, clothing, objects, and people. Axon’s body cameras and drones are already capable of feeding into this system. As these systems sell for $25,000 to $100,00 per year, Axon is set to make a pretty penny off of this acquisition.

![[F]law School Episode 12: The Body (S)camera](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/POOKKULAM_HERO-e1728232922783-640x427.jpg)