Private Investment in a Public Good

A look at the Intersection of Water Law and Corporate Law

Grace Summers

June 19, 2024

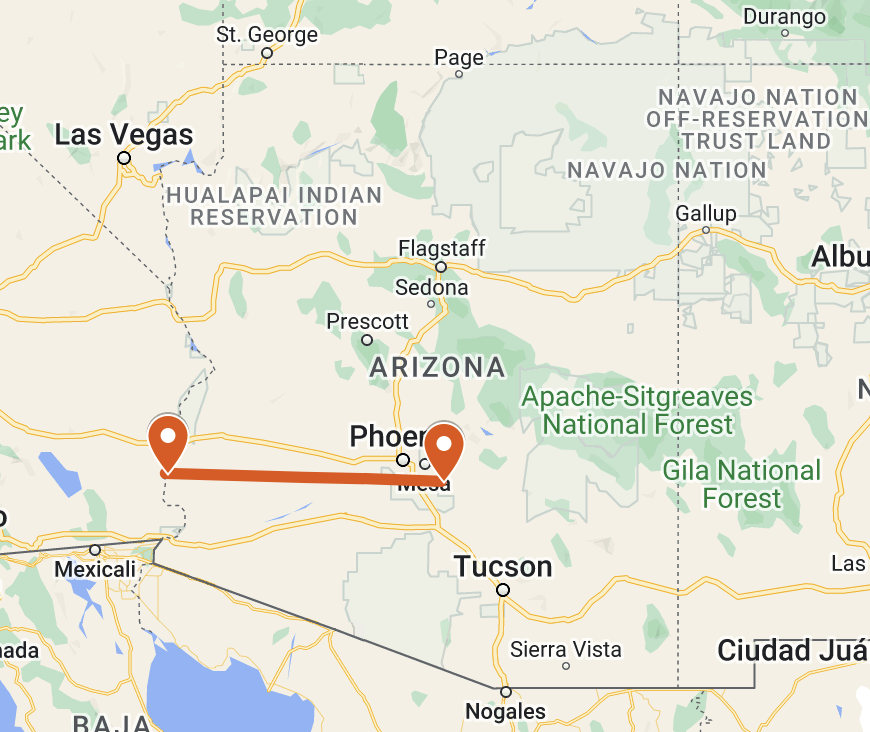

The vast fields of vibrant green growing stark against the surrounding desert landscape of southwestern Arizona were more than just eye-catching. In April of 2023, the fields of alfalfa also caught the attention of national news outlets when they uncovered a story eight years in the making: a Saudi Arabian company was pumping groundwater in Arizona, and they were pumping a lot of it. Fondomonte, a subsidiary of a massive Saudi dairy company Almarai, had been using thousands of acres in La Paz County, Arizona to grow alfalfa as cattle feed. After harvest, Fondomonte was shipping the crop all the way back to the Arabian Peninsula for consumption by Almarai’s 195,000 head of cattle.

The story made headlines for several reasons. First, and most obvious, Arizona is not particularly known for its abundance of water. Moreover, alfalfa is an unusually thirsty crop, requiring an estimated five acre-feet of water per acre of crop. Almonds, another notoriously water-intensive crop, require roughly 4 acre-feet of water per acre of crop, and the average American household uses less than half an acre-foot of water per year. Despite the limited availability of water, Fondomonte did not have any restrictions on water use on its Arizona farms.

Media attention brought outrage and increased scrutiny, and ultimately Arizona declined to renew the company’s land leases. But for 8 years Fondomonte was able to profit off unlimited groundwater pumping in Arizona, with little to no costs.

Fondomonte, however, is not the only corporation that has been eyeing opportunities with water in the western United States. Private investment firms have their sights set on profiting off water, and to do so, they have begun to purchase water rights in Western States. But to understand the growing interest in water rights, and how an investor can be profitable in the face of drought, it is helpful to understand the arcane water law that governs the American West.

As early settlers made their way west in the United States, they found a landscape very different from the lush East Coast and Midwest. Water was no longer plentiful, and the legal doctrines imported from a similarly wet England, where water rights were tied to land alongside rivers and streams, made little sense. With limited surface water sources, people had to dig ditches or otherwise pump water from afar to make land arable.

To govern this new landscape, a new legal regime sprouted from the roots of mining law in the 1800s: the first to claim the surface water and put it to use would gain a property right in the water. Given the amount of work required to divert water from a source and move it to a tract of land, the courts and state governments ultimately supported this new legal approach in hopes of encouraging western land development. This system, called Prior Appropriation, is one based on seniority, giving rise to the phrase “first in time, first in right.” As more users appropriate water from a given source, the new surface water rights established are more junior to the rights of those who had come before them.

Water law, however, continues to be haunted by the settlement and development focus of the 1800s. In times of scarcity, senior appropriators have their full water rights fulfilled before more junior appropriators receive any water, rather than some form of proportional diminishment. Water rights are also subject to a “beneficial use” standard meaning the water must be put to an appropriate use. Otherwise, an appropriator might lose a water right via “abandonment.” In other words, “use it or lose it.” Non-use for modern conservation efforts is generally not recognized as a beneficial use.

For similarly archaic reasons, groundwater is also treated differently under the law. At the time western water law was developing, groundwater was not scientifically well understood. Although modern science now recognizes the connection between surface water and groundwater via the hydrologic cycle, the law developed separately, treating each source of water as distinct and unconnected from the other. Historically, groundwater rights were associated with land ownership and landowners could pump however much water below their land as they wanted. While states eventually developed more nuanced groundwater doctrines and implemented groundwater regulations and permitting requirements as groundwater use increased in the twentieth century, the legal division between surface water and groundwater remains.

Western water law has not adapted well to growing scientific knowledge, both in understanding the connections between surface and groundwater and in the recognition that scarcity conditions require different management standards.

Investors, however, have recognized a potential for profit within this system. Water rights in both surface water and groundwater function as property rights, and these rights are transferrable. Some of these property rights are also more valuable than others. Very senior surface water rights guarantee water delivery, even in years of drought. Similarly, groundwater rights with limited or even no restrictions provide access to an underground water source that is less dependent on changing weather patterns. While demand for water continues to grow, water itself grows more scarce, increasing the value of water rights in the West. To take advantage of the potential increasing value, investment firms have been targeting and acquiring water rights in Western States.

One oft-cited firm makes its goals clear, titling itself Water Asset Management. But other prominent investors are also joining this new world of water investment. Michael Burry, famously depicted in The Big Short for his foresight of the 2008 mortgage crisis, noted that one of his major focuses moving forward is trading in water as an investment vehicle. And even Harvard University has begun buying up farmland rich with water rights in California.

Water rights in both surface water and groundwater function as property rights, and these rights are transferrable.

While there are a variety of ways to invest in water, a typical investment takes the form of purchasing agricultural land with strong associated water rights. For surface water, this means the water rights associated with the land are more senior on the priority list. Although groundwater investments will differ depending on the state’s individual groundwater law, investments are likely to be associated with land overlying strong aquifers or groundwater basins. Harvard, for example, targeted vineyard farms overlying one of the largest aquifers in the western United States.

ImageFX by Google, AI Generated Image

After a firm invests in water rights, however, the water use doesn’t immediately change. “People want to paint this as a Wall Street hedge fund that is buying up Arizona’s water, ruining agriculture,” says Grady Gammage, Jr., an Arizona-based lawyer who has represented one of these firms in water investment deals. “In fact, what they have done is buy farmland and farm it.” A Colorado water lawyer, James Eklund, echoed these sentiments, noting “the investors I’ve worked with in private equity are leasing the farms back to the families to keep the land in ag production.” In the short-term, investment firms maintain ongoing agricultural activities.

While part of the reason behind continued farming is the need to put the water to “beneficial use” to maintain the water right, this also makes a deal more appealing to farmers. Farmers receive potentially significant purchase prices but can remain on the land and continue to farm in the near-term. Additionally, it presents a lucrative retirement plan for small, generational farms. “Agricultural folks that I’ve spoken to, they have sons or daughters that aren’t interested in continuing farming anymore,” says Mohave County Supervisor Travis Lingenfelter who serves a region with a number of agricultural communities in Arizona. “These corporations come in and they make them an offer that’s just too good to refuse.”

Proponents of investment in water also believe that outside investment will encourage a more robust water market that could help solve water scarcity issues in the West. But water market advocates also recognize that buying and selling water is often viewed negatively by the public. Eklund describes how an average person might react to the idea: “If you asked the average person, ‘hey, do you think we should let private companies own water?’ They’d say, ‘No way.’ But if you explain, ‘Well actually we’ve operated a system of water use as a property right capable of private ownership in the West since before statehood, just like real estate,’ they’d say ‘oh, ok, well if it has been functioning like that, I guess I wouldn’t want someone limiting what I can do with my assets.’”

In some sense, there has always been some kind of market for water; water rights have always been able to be sold and transferred to other users. Historically, however, water markets haven’t been explicitly targeted for profits by investors. Instead, water transfers have taken place when new users enter a system, or old users leave.

Proponents of investment in water also believe that outside investment will encourage a more robust water market that could help solve water scarcity issues in the West.

“Demand for water has changed and evolved over time,” says Ellen Bruno, an agricultural and resource economist at University of California-Berkeley, “and the historical assignment isn’t going to be right today.” As water demands change, water rights can be transferred to meet the needs of today. This, economists note, is a good thing. “The benefit of allowing the trade of water is so that we can achieve some sort of allocation that we think overall is a better use of that water” says Bruno. For example, as populations grow in western cities, it is helpful that those cities can acquire more water rights to meet their citizens’ needs.

But just as the demand-side has changed, so has supply. As Andrew Ayres, an environmental economist at University of Nevada-Reno, notes, water markets perform an important function in “enabling our society to be able to move water around effectively as scarcity conditions dictate.” As the supply of water in the West fluctuates, water markets allow users to sell or buy water as they see fit.

As scarcity increases, Ayres sees another benefit of water markets: “conflict reduction.” Because water markets make clear who has water and thus who another party can negotiate with to purchase more water, “that reduces conflicts in terms of bringing together parties collaboratively instead of having them compete in a political arena for access to water.”

Investors, however, are a different and new type of player in water markets. Unlike other stakeholders whose interest in water is putting it to use, investors who purchase farmland are not interested in the agricultural use of water. “Their principal motivation is not long-term farming, but it is the value of the water,” Gammage says of investors. Although investment firms will often lease land back to farmers after the initial purchase, over time water rights will likely increase in value and eventually be sold or leased to the highest bidder.

Some who work in the water space view investors as positive additions to western water markets by helping solve some of the existing problems in the marketplace. “Transaction costs are really high in water markets,” notes Professor Ayres. “Investors are another entity alongside traditional water users who are in a position to invest in overcoming transaction costs, whether that’s building infrastructure, stoking collective action to change rules around moving water, or just doing the fact-finding and market-making that is necessary to find buyers for sellers of water.”

Modern complaints about western water markets, including pricing discrepancies and lack of conservation, are rooted in how water was historically allocated and how the law works. Agriculture and mining were the two original sources of western development, and many of the original water appropriators of the west were farmers who cultivated the arid landscape. Vast amounts of water rights, especially senior rights, have remained in the hands of farmers and irrigation districts. Today, over 80% of western water is allocated for agriculture.