Dr. Mara Grujanac, an elected trustee for the Village of Lincolnshire, Illinois (population: 8,000), is one of those lawmakers.

“The blinders came off as a public official,” said Grujanac of her unintentional run-in with ACCE.

In December 2015, Grujanac was the only trustee on the six-member board to vote no on an ordinance to make Lincolnshire a “right-to-work” municipality. Right-to-work laws forbid labor organizations and employers from entering into union security agreements, which require all employees—not just union members—to pay union dues. These agreements are intended to solve the free rider problem that can arise when a union must represent an entire workforce, but only a portion of the workers contribute to the cost of that representation. The anti-labor movement has fought for decades to ban union security agreements, with success in at least 22 states.

Their next target? Local governments.

Grujanac said she was and is personally opposed to anti-union laws. What troubled her most about the 2015 ordinance, though, wasn’t the content of the proposal—it was the “backdoor politicking” that surrounded its passage.

A few weeks prior to the official introduction of the right-to-work ordinance, Grujanac started hearing murmurs about an upcoming vote; the purpose and motivation of the law were left vague. Other players in the Lincolnshire local government tried to convince her it was just another ordinance.

“It was slightly touched on, but sort of like baloney. You know, like it’s nothing,” said Grujanac. “But I had been on the Board long enough to know: I think this is not going to be a baloney thing.”

“The takeaway for me, all these years later, is that we got busted doing shady things,” said Grujanac. “The Village of Lincolnshire tried to do all sorts of shady stuff and got busted. And I think it was right.”

Leading up to the monthly Village Board meeting at which the ordinance would be debated and voted on, Grujanac was told in private that the right-to-work law was intended to court a “big corporation” which was looking to site its headquarters in Lincolnshire—but when she asked for more information on the corporation and the alleged deal, she was refused.

“It was this whole secret, like, ‘I can’t tell you,’” said Grujanac. “And so that was off-putting.”

According to Grujanac, the Village of Lincolnshire is no stranger to catering to commercial interests: The area is home to a number of corporate headquarters, drawn in by the municipality’s business-friendly policies as well as its celebrated public high school, where Grujanac works. That this particular deal was taking place off the record, however, Grujanac thought was unusual.

Before the vote, Grujanac took things into her own hands. “I start to do a little bit of digging behind the scenes,” she said. “I do some homework on it, and I realize this is a union-busting vote.”

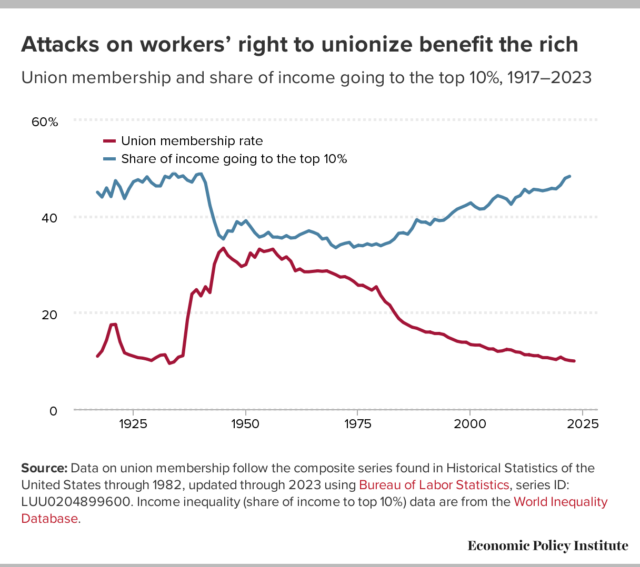

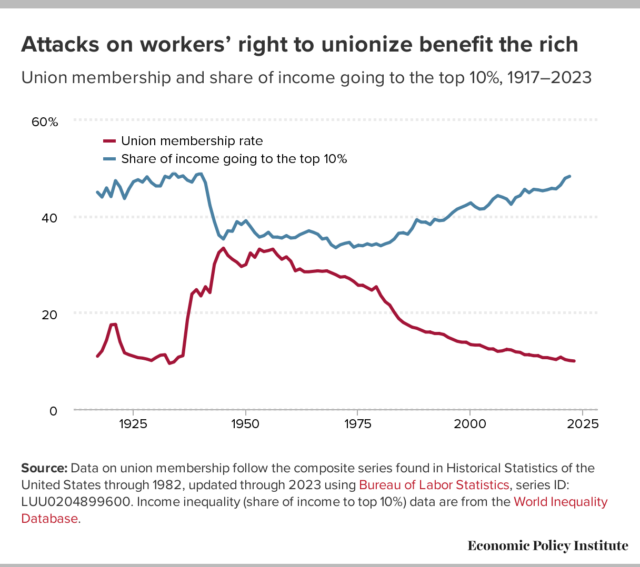

Higher rates of union membership are correlated with reduced income inequality; anti-union policies like right-to-work laws suppress worker wages and widen that gap. Used with permission of the Economic Policy Institute.

Local labor unions and workers caught on, too—when Grujanac arrived at the Village Board meeting that night, an inflatable rat was set up in the Village Hall parking lot, and dozens of people had lined up to speak in favor of and against the ordinance.

After just an hour of discussion, though, Lincolnshire Mayor Elizabeth Brandt cut off public comment. Grujanac remembers asking questions at the meeting, all of which went unanswered. The Board proceeded with the vote, and the ordinance passed 5-to-1.

“I wanted to see if she was going to come out in public and say something,” said Grujanac of the mayor, “because I felt that it was politically motivated. I just felt that we were not doing this for a real reason. We were doing this because someone tried to talk someone else into it.”

“I know in Maine you must register as a lobbyist if you are before the Legislature or the Executive Branch,” said Cushing. “There is not, for most communities, a requirement that you are registered per se to lobby at the local level.”

As it turns out, Grujanac was probably right. Local “right-to-work zones” were a core agenda item for then-Governor of Illinois Bruce Rauner, whose administration had close ties to the Lincolnshire government: Brandt served as campaign chair for Rauner’s deputy governor, Leslie Munger, during Munger’s run for state comptroller.

Lincolnshire was the first and last Illinois municipality to follow Rauner’s advice. Within weeks, a number of labor groups had sued the Village of Lincolnshire in state and federal court, arguing that the ordinance was unlawful and that Brandt prevented union members from speaking at the Village Board meeting. The Village agreed to settle the state suit for $10,000 paid by the Liberty Justice Center, the conservative Chicago-based litigation group representing the Village, which would go on to back the plaintiffs in a landmark anti-labor Supreme Court case barring union security agreements for public employees. A federal court struck down Lincolnshire’s law in 2017.

For good measure, the Illinois General Assembly followed up with a state law banning local right-to-work ordinances, and Illinois voters approved an amendment to the state constitution in 2022 which barred right-to-work across the state.

“The takeaway for me, all these years later, is that we got busted doing shady things,” said Grujanac. “The Village of Lincolnshire tried to do all sorts of shady stuff and got busted. And I think it was right.”

Grujanac learned later that the “big corporation” looking to set up shop in Lincolnshire had decided to locate elsewhere. Grujanac never knew, however, that the ordinance hadn’t originated in the Village of Lincolnshire—or even in the Governor’s office. In fact, the text of the right-to-work ordinance was almost identical to a model policy published by ACCE in January 2015.

ACCE’s fingerprints had been wiped from Lincolnshire’s ordinance, a common feature of “copy-and-paste” or “copycat” legislation originating from outside organizations and marketed to legislators across multiple bodies of government. State and federal policy is often similarly untraceable, but disparities in openness and access to resources are even more pronounced at the local level, making it harder for people to figure out who is drafting their community ordinances.

For these same reasons, local lobbying is often easier for corporations and organizations to hide; most citizens aren’t even aware they should be on the lookout for private influence.

At a fundamental level, not all states define “lobbyist” the same way—sometimes an individual must spend a certain amount of money or time on lobbying to be an official “lobbyist.” All 50 states have laws which require state government lobbyists (and sometimes the entities that employ them) to file registration paperwork, but local government lobbyists aren’t always covered. Some municipalities, like the City of Boston, have their own lobbying regulations altogether, but some have none at all.

The information lobbyists must disclose on this paperwork varies widely from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and on top of it, statutory filing and disclosure requirements aren’t always clear. As a result, the agencies responsible for reviewing these disclosures have broad discretion in determining whether a lobbyist is in compliance.

Indeed, even Cushing—the director of a nationwide organization which publishes model ordinances, hosts conferences of local officials, and facilitates relationships between corporate interests and municipal governments—doesn’t need to register as a lobbyist to do his job.*

“I know in Maine you must register as a lobbyist if you are before the Legislature or the Executive Branch,” said Cushing. “There is not, for most communities, a requirement that you are registered per se to lobby at the local level.”

Apparently, there might not be such a requirement at the state level, either. ALEC and its subsidiaries are a 501(c)(3) organization, which according to the IRS “may not attempt to influence legislation as a substantial part of its activities”—meaning it isn’t technically a lobbying group. That designation has, understandably, raised eyebrows. As insurance, ALEC has managed to secure exemptions from at least three separate states allowing it to avoid registering or disclosing its lobbying expenditures, and it has created a sister 501(c)(4) organization, the Jeffersonian Project, which can (and does) lobby more openly.

This complicated collage of local, state, and federal laws means that a lot of activity—from ALEC, ACCE, and other, lesser-known interest groups—falls through the cracks. What’s worse, even properly reported lobbying can be tough to monitor. Following the death of the local paper, people receive little help in keeping tabs on their local governments—unless, of course, you’re a public affairs professional (or a lobbyist) with access to cutting-edge and costly local policy tracking software.

When it comes to local lobbying, this ease of concealment was at one point outweighed by the difficulty of reaching hundreds, if not thousands of discrete municipal government bodies. Decentralization used to cut both ways: Corporate interests could target local officials to evade state lobbying schemes, but only with a lot of money and time. Rather than meet with a handful of representatives, lobbyists had to convince city and county governments piecemeal to elect business-friendly officials or enact ordinances protecting corporate interests.

Technology is starting to erode these practical safeguards.

“It is easier to lobby municipalities than it’s ever been. Anybody could do it,” said Tierney, citing social media and videoconferencing as means by which an out-of-town lobbyist can reach voters in towns across the country without ever leaving their corner office.

![[F]law School Episode 10: Mass Incarceration, Inc.](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/RICHARDS_PHOTO_Protest2-640x427.png)