Stewards of Philanthropy

Nonprofit unions fight for workplace democracy in the nation’s least democratic sector

Tamara Shamir

November 12, 2023

The Southern Poverty Law Center Union was clear about its mission from the start: disrupt white supremacy, pursue equity, and build solidarity. What was less evident to those outside the Southern Poverty Law Center Union was why workers at an organization that prides itself for expanding worker’s rights and power needed a union at all.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) is one of the great liberal stalwarts of the South, renowned for calling out hate groups and expanding civil and labor rights in courts. However, a growing voice had a different story to tell, of an organization plagued by the same structural issues it was attacking in court. Employees described a racially stratified workplace, where white employees tended to hold higher-ranked and better-compensated positions and Black employees worked under-compensated jobs in administrative and support staff. Moreover, SPLC’s co-founder, Morris Dees, faced multiple sexual and racial harassment accusations. (SPLC’s internal investigation found no misconduct; the victims, bound by non-disclosure agreements, could not speak out.)

Although the old regime was eventually ousted—Morris Dees was fired in disgrace—the structural inequalities that enabled his abuse remained intact. “A lot of the issues—discrimination, sexual harassment, systemic racism—are still very much prevalent,” said said Lisa Wright, a member of the union’s bargaining committee who has worked at the SPLC for over 20 years. “They’re still huge issues, especially for the Black women within the organization.”

Talk of a union had preceded Dees’ resignation; after his departure, the conversation intensified. The workers who had rallied for new leadership believed they needed a union to enshrine and expand the protections they had fought for.

The union that would help catalyze a transformation of the entire nonprofit entire sector was planted in hostile soil. The SPLC refused to recognize the union, forcing the organizers to administer elections through the National Labor Relations Board. That started things off “on the wrong foot,” said Esteban Gil, a Program Associate and early organizer of the SPLC Union. But he wasn’t surprised: “A boss is a boss is a boss . . . whether they’re ‘progressive’ or not, they have interests that do not align with our interests as workers.”

“A boss is a boss is a boss . . . whether they’re ‘progressive’ or not, they have interests that do not align with our interests as workers.”

The SPLC’s Chief of Staff, Lecia Brooks, understood the “positionality in terms of power” across sectors, but still hopes that a nonprofit boss is different. “With social justice organizations, we didn’t want to enter into the traditional kind of adversarial [relationship]; we’re not Amazon…We hold our managers to the mission statement, that, you know, we’re fighting against injustice.” It’s been the “big sadness of going through the negotiation process,” Brooks said, to enter a frictive relationship with the workers. But staff and management, Brooks believes, are “moving back together.”

“Nonprofits are like faux-families, and those are real tensions,” Brooks said. “I regret a lot of it. That it was so tense and ugly, and that people felt bad, [that] lots of people left. It wasn’t what they signed up for.”

Despite this, Brooks maintains that the union benefitted the organization. In fact, she saw the SPLC’s unionization as inevitable. “That’s where the movement for workers was going,” she said. SPLC, which unionized in the winter of 2019, was “a little bit ahead of the curve.”

In fact, following in the footnotes of the SPLC, nonprofits have been unionizing at a remarkable rate over the past few years. The Nonprofit Employees United has unionized workers of 68 organizations since 2019, growing from 12 organizations in 2018 to almost 50 organizations and 1,500 workers today.

According to David Zonderman, who teaches labor and nonprofit history at North Carolina State University, as nonprofits shift towards corporate modes of governance—focusing on efficiency and optimization of labor output—workers have needed a response rooted in the corporate world.

“The older generations have this view that, you know, unions are for blue collar guys tying wrenches on the auto-assembly lines,” said Zonderman (He later referred to these unions as “pale, male, and stale.”) The majority of the workforce isn’t blue collar anymore, he added; it’s “lower white collar” or “pink-collar… More and more unions today are working in that reality.”

A few decades ago, “pink-collar” work—traditionally feminized care work such as nursing, teaching, or the type of community-facing work often found in direct service nonprofits—was not included in the class of workers normally associated with unionization. As workers move from industrial jobs into service sector jobs, unions have, at times reluctantly, caught up.

This new reality is a far cry from the origins of the union movement, which was dominated by an anti-Black, anti-women, and anti-immigrant sentiment and policy. To this day, the National Labor Relations Act excludes certain occupational categories with majority Black and majority female workers—most notably, agriculture and domestic care.

Professor Sharon Block, the executive director of the Center for Labor and a Just Economy at Harvard Law School, believes a turning point was the Fight for 15 in the 2010s. The Fight for 15 started with a nation-wide fast food worker’s strike and expanded to home health aid, teachers, retail, and healthcare, eventually becoming a vast political movement for nation-wide minimum wage. This movement, Block said, “awakened the idea of collective action and concerted activity on a scale that was really different.”

National approval of unions reached a historical high last year, with 71% of the population broadly pro-unions, according to the Gallup poll—the highest number recorded since the mid-60s. This number includes a significant jump after the pandemic, which sharpened many workers’ concerns with workplace safety and job security. The pandemic, moreover, pushed a sheltered-in-place population deeper online, where BLM, #MeToo, and other progressive movements instilled young workers with a new political fervor.

“[The younger] generation has now been through the great pandemic and the great recession,” Zonderman said. “You’ve learned the hard way about economic uncertainty.” The new generation of workers are drawn to the collective action and countervailing power offered by unions; the type of idealistic and social justice oriented workers who enter the nonprofit sector might be especially motivated.

Despite the expansion of unions into new sectors—and the public consciousness—most nonprofit management claim that unions are incompatible with nonprofits. Nonprofit unions faced similar responses from management: that mission-driven nonprofit organizations have neither the adversarial labor relationship that necessitates a union nor the financial elasticity to accommodate its behest. Some managers told their unions that their boards and funders would refuse to pay for higher wages; some even went to the public to claim that unionization would raise their costs and allow them to serve fewer people.

SPLC, however, could hardly claim it lacked the revenue to meet the union demands—SPLC’s net assets and funds hover around $700,000,000. However, it still admonished the new union that SPLC and its workers had to be “good stewards of donor resources,” Wright recalled. The SPLC seemed concerned about the optics of inflating wages beyond industry norms—of being perceived as weak for capitulating to worker demands.

The SPLC’s Chief of Staff, Lecia Brooks, said that there was no concern about what donors would think of raising wages. Donors wanted management to settle with the union quickly, she said: “SPLC supporters and people who support social justice are in favor of workers rights.” When asked what pressures kept staff wages depressed, Books pointed to the workers’ placement in “low wage states” such as Mississippi and Alabama.

Professor Zonderman has little sympathy for nonprofit management’s reluctance to wage salaries regardless of what drives it. “I would say, take a real hard look at what top management salaries are in the nonprofit,” Zonderman said. “How about you sacrifice a little bit of your salary? Instead of saying we’re going to stop helping a certain number of people because we don’t have money?” (In 2021, Margaret Huang, the CEO of SPLC, earned $444,850; the top C-suite made close to a quarter million. Meanwhile, pre-union, one legal assistant reported living over 50 miles away from the Decatur, Georgia office to afford housing with a salary under 30K.)

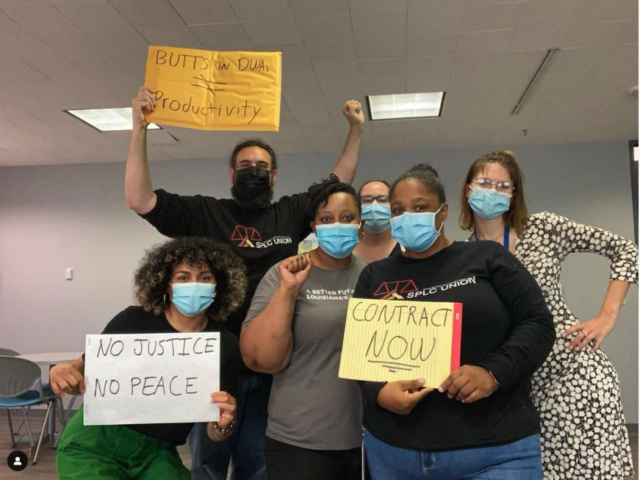

Image provided with permission from SPLC Union’s Instagram.

In an important sense, however, the funding and elasticity debates miss the mark. The idea that unions do not serve a purpose if revenues are too inelastic to raise wages is based on a misunderstanding of the project of unionization. As Sharon Block explained, nothing about the unionization process guarantees a wage increase or requires more revenue.

“What labor law promises employees is not an outcome but a process,” Block said. Unions create a forum for workers to communicate with management and a “mandate” of a minimum transparency for management—not a guaranteed income boost.

Yet many nonprofits seemed unwilling to engage with the process that unions promise workers. Nonprofit organizations resorted to costly anti-union efforts to avoid coming to the bargaining table, such hiring specialized “union avoidance” law firms, mandating captive audience meetings with anti-union messaging, and delaying the bargaining process by offering inadequate negotiation times.

“[Nonprofits have] gone and hired some of the leading union thugs with briefcases,” said Zonderman. “It’s like, what happened to your mission statement about saving the world? If you believe that, shouldn’t you walk the walk?”

Wright and her colleagues tried to convey to the SPLC that its support staff—low-income workers, majority Black and Brown, subject to anti-union tactics, legally vulnerable to sexual and racial harassment—deserved the same solicitude that the SPLC offered to those outside the organization. “We’re also part of the community and you have to also take care of us,” Wright said.

SPLC, however, appeared unwilling to apply its labor policies internally. Despite its public commitment to redressing “anti-union laws,” “weak…labor protection,” and “low wages,” it offered the workers only two hours a week (rather than the longer consecutive sessions workers asked for) to slow the bargaining process.

Initially, the SPLC hired a private law firm that specialized in union avoidance strategies called Hunton Andrews Kurth. According to Brooks, the attorney was not chosen because of roots in an anti-union firm, but because the interim president, the first Black and female president of the SPLC, wanted a Black and female lawyer, and failed to vet her properly. “When we learned that they [Hunton Andrews Kurth] were management-side, union-busting law firms, we changed course, we let her go,” she said. In her place, the SPLC hired a labor-side attorney.

However, according to Halyley Brown, President of the Nonprofit Professional Employees Union, nonprofit hostility towards unions is not an accident or aberration, but a product of the sector’s very structure. The nonprofit funding system, Brown explained, is structured to incentivize “pil[in]g workloads” and “hav[ing] as many people as you can agree to work for the lowest wage.” There is a finite pool of foundation and donor resources: to get contracts with foundations or popular support, each nonprofit must edge out its peers in its ability to to keep costs low and please its donor base. Often, they need to show a certain number of clients served through their grants. The money, moreover, typically comes with specific conditions, leaving management unable to use it for PTO or employee benefits.

The SPLC’s reputation may grant it a certain freedom, but the basic facts of the sector remain. To preserve their funding, nonprofits must constantly prove that they’re operating in an efficient and output-maximizing way—even at the expense of their employees. Nonprofits may not be competing in the market, but they are still trapped in a fierce and competitive race to outperform and undercut—a perpetual race to the bottom.

Nonprofits may not be competing in the market, but they are still trapped in a fierce and competitive race to outperform and undercut—a perpetual race to the bottom.

According to Brown, the current model for nonprofit labor is similar to research assistants at universities: pay young and idealistic people very little as a “stepping stone to graduate school” or higher-paid work elsewhere. “But if you think something is important, why would you expect it to be done solely by volunteers?” Brown asked.

The SPLC Union agreed. At the bargaining table and in public, they pushed for the SPLC to apply its labor politics to its own staff. The union remained ambitious. “We’re thinking about a world where everyone is safe,” Wright said of the union. “We’re thinking about a world where everyone is valuable.”

Slowly, the SPLC Workers union took small steps towards this world. They negotiated a contract enshrining protections against sexual harassment and discrimination and prohibiting NDAs for sexual and racially discriminatory misconduct. Eventually, they secured raises of up to 65% for SPLC’s support staff.

For Wright, the greatest moment was getting to call her coworkers to share the pay raises and increases in benefits. Before the union contract, people were working a second job to survive, Wright said. They were living off their credit cards. Now, they could subsist on one salary. As part of a unionized workforce, moreover, SPLC’s workers gained access to grievance and arbitration processes. They created a collective voice on public platforms to call out management (and frequently do).

“It feels different now,” Wright said of working in a unionized workplace. “But we still have a lot of work to do. Is it the safest place? No. But is it safer than when we first started? Absolutely.”

Esteban Gil, left, and Lisa Wright, right, early organizers of the Southern Poverty Law Center Union. Images provided by Esteban Gil and Lisa Wright.

Her colleague, Esteban Gil, agreed: “Workers at SPLC are organized and talking to each other. They’re not alone. They’re engaged in a collective experience of workers in struggle. And that—just our mere existence—shifts the power dynamics.”

This countervailing power, while radical, was still not enough. The union had set out to “make workplace democracy a reality,” Gil said. But the union’s vision—one where power was transparent, justly distributed, and shared with workers—remained out of reach.

In a large nonprofit, according to Brooks, it’s just not possible to create a full democracy. “You can’t have almost 400 people in a democratically run workplace.” However, workers have been given a larger voice through committees and task forces modeled on the worker’s bargaining team that help determine the strategic direction of the SPLC itself.

Gil did not feel that the SPLC implemented significant power-sharing. “Anytime we were asking for more power, anytime we’re asking for more accountability and decision making for more of a seat at the table is when we ran up against difficulty and intransigence,” he said. With a leadership system too opaque to even pinpoint who was calling the shots and how to hold the decision-makers accountable, it was almost impossible to get workers’ “hands on the steering wheel.”

According to Professor Benjamin Sachs, a professor of labor law and relations at Harvard Law School, unions provide a response to the endemic power asymmetry between management and workers. These inequalities “don’t stop at the factory door,” he said. “Unions are about labor. And this is labor.”

The project of workplace democratization is needed in every sector: however, it faces unusual barriers in the context of nonprofits, where power is not only concentrated at the top, but also hidden out of sight and often out of reach—in the Board, major donors, and foundations. Nonprofit unions must contend with a source of power more layered, opaque, and slippery than their counterparts in the for-profit world.

The project of workplace democratization is needed in every sector: however, it faces unusual barriers in the context of nonprofits, where power is not only concentrated at the top, but also hidden out of sight and often out of reach—in the Board, major donors, and foundations.

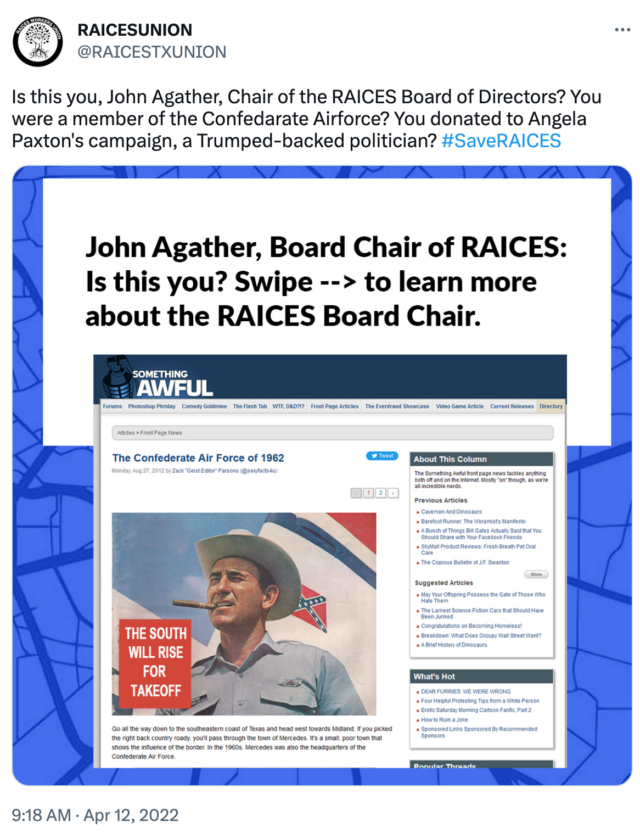

One of the fiercest struggles against this elusive power—and the story most revealing of both the urgency of nonprofit unions and the limits of their power—is the controversy-laden unionization of the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, better known as RAICES.

In the mid 2010s, RAICES staff were at-will employees facing a series of punitive and retaliatory firings. Employees did not have full health insurance, with some paying four digits out of pocket for their monthly coverage. Salaries were low, especially for legal assistants and support staff.

Then, around 2017, money began to pour in. As outrage over family separation brought immigration policy to the forefront of the national consciousness, donors and foundations alike channeled their indignation into concrete financial support. Overnight, RAICES transformed from a small community service organization to a well-funded organization with a national presence and a large legal staff. Its revenues jumped from $6,944,849 in 2017 to $56,263,200 in 2020. It hired 137 new employees and opened new offices in San Antonio, Houston, and Dallas. Its Twitter following grew from 2,000 to 76,000.

“I think there was a sense on staff that there was this influx of cash, right. And we could see people up at the top of the organization benefiting from that,” said Kate Richardson, a staff attorney at RAICES and one of early organizers of the union. While RAICES offered its non-managerial employees some gestures of goodwill—what Richardson described as “sporadic and uneven” salary increases—it declined to use its new wealth to create any systemic improvements for its workers.

“Everyone could see the money,” Richardson explained. But the decisions on how to wield it were “made in a little black box.”