But even as the use of boarding schools fell out of fashion, the methods of forced assimilation continued. In 1958, the Bureau of Indian Affairs funded the Indian Adoption Project, which purported to find homes for “forgotten” children who were “left unloved and uncared for on the reservation, without a home or parents he can call his own.” This program’s underlying principle was eerily similar to that of the boarding schools: removing children from their native families would provide a “better” life. The program lasted until 1967. By the 1970s, state welfare agencies – in tandem with private adoption agencies – became the primary entities responsible for unjustifiably removing Native American children from their homes. In that time, 25-35% of all Native children were removed from their homes by state welfare and private adoption agencies. Of those removed, 85% were placed outside of their families and communities.

Tribal Advocacy Leads to the Passage of ICWA in 1978

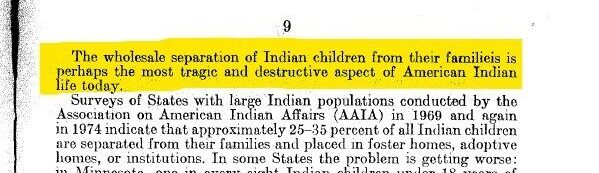

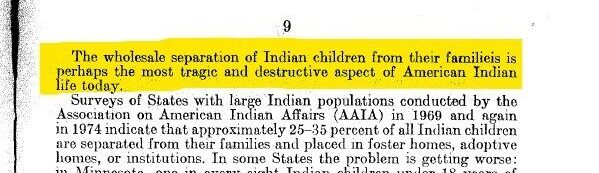

Tribes consistently appealed to Congress about the damage being done to their communities by outside actors removing children from their homes. In a series of Senate hearings in 1974, families recounted stories of children who were taken by the state without notice or court hearings, welfare agents repeatedly asking that mothers give up their newborns, and kids making plans to hide if child services showed up to take them away. Upon the completion of a Congressional investigation into these practices, Congress released a report acknowledging that “[t]he wholesale separation of Indian children from their families is perhaps the most tragic and destructive aspect of American Indian life today.”

An excerpt from the Congressional report on “Establishing Standards for the Placement of Indian children in Foster or Adoptive Homes, to Prevent the Breakup of Indian Families, and for other Purposes.” 2 H.R. Rep. No. 95-1386 at 9 (1978)

In response to Native American advocacy and testimony during Congressional hearings, Congress passed ICWA in 1978 with bipartisan support. The text of the law makes clear that protecting Native American children is “vital to the continued existence and integrity of Indian Tribes,” and acknowledged that “an alarmingly high percentage of Indian families are broken up by the removal, often unwarranted, of their children from them by nontribal public and private agencies and that an alarmingly high percentage of such children are placed in non-Indian foster and adoptive homes and institutions.”

“Families recounted stories of children who were taken by the state without notice or court hearings, welfare agents repeatedly asking that mothers give up their newborns, and kids making plans to hide if child services showed up to take them away.”

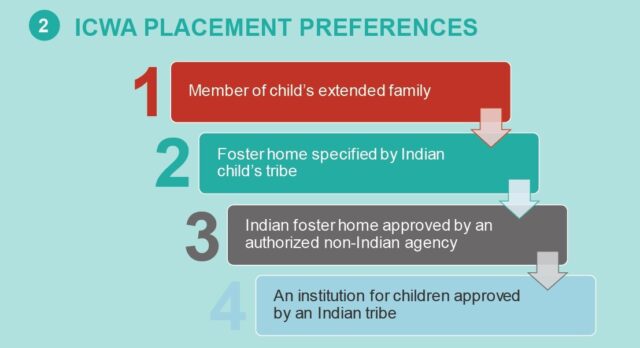

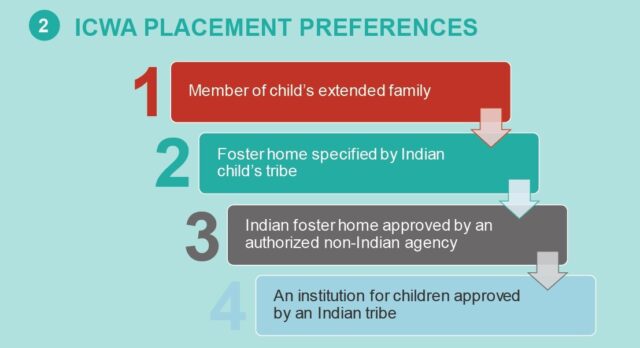

ICWA counters these practices by enshrining into law policies that prioritize kinship placement to keep Native families and communities together. First, ICWA requires states to make “active efforts” to keep Native children with their parents. If this is not possible, the state must first try to place the child with a member of their extended family; second, with another tribal member; and finally, with an unrelated Native American family. Only after these avenues have been exhausted may the child in question be placed into the state’s general adoption or foster care system. ICWA subverts the historical practice of removing Native children from their homes, sometimes without their extended family or tribe even being made aware the child was taken into the state’s custody. The process helps ensure that tribes, as sovereign nations, have jurisdiction over their own children.

Graphic from the National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) at nicwa.org.

ICWA has now been in place for more than 40 years and is supported by hundreds of federally recognized tribes and the nation’s top child welfare organizations. The Children’s Defense Fund and the Casey Family Foundation have called ICWA the “gold standard” in child welfare policy, due to its prioritization of kinship placements. The Casey Foundation describes ICWA as “ahead of its time,” and highlighted the law’s recognition of the “core values and principles of child welfare best practice by requiring active efforts to keep children safely in their homes and connected to their families, communities, and culture.”

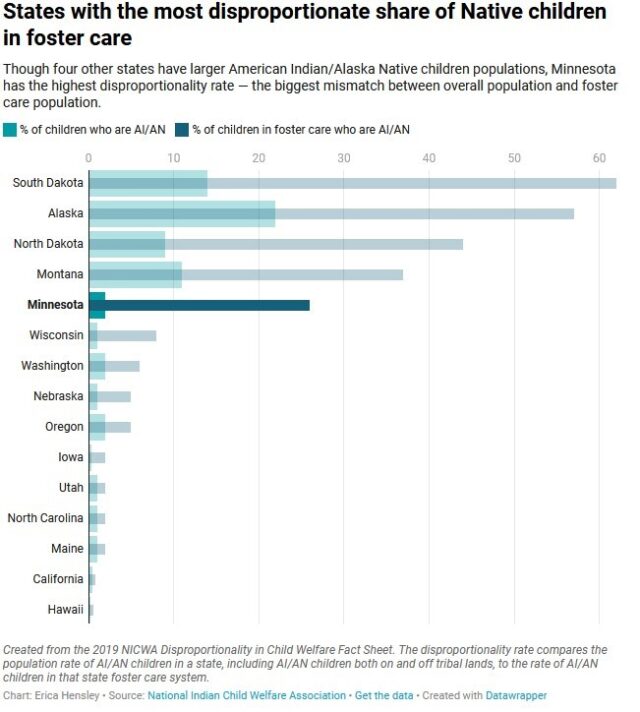

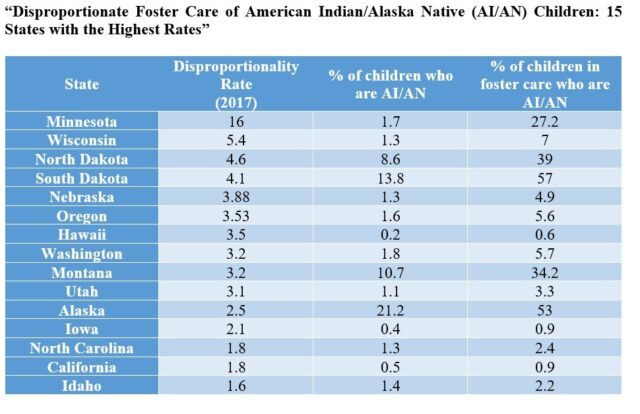

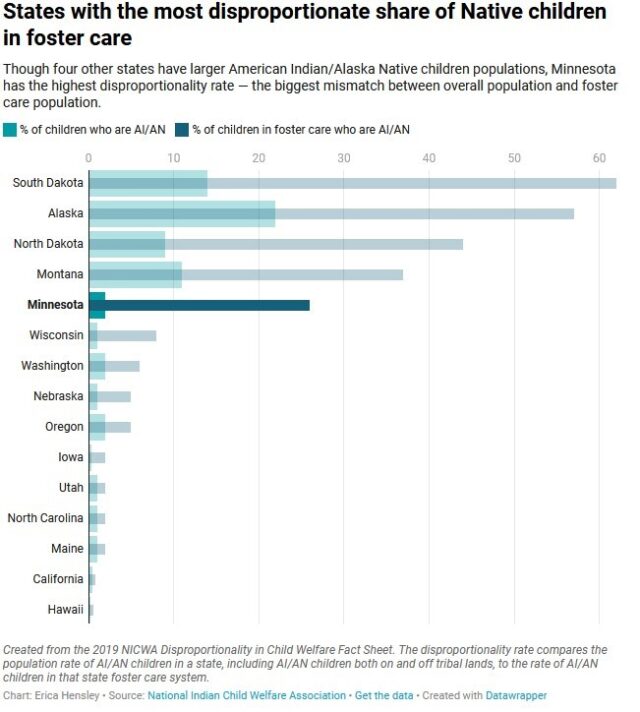

Unfortunately, many states have worked to get around ICWA’s protections, or have simply failed to follow the required steps. These actions have continued to create situations where Native children are disproportionately removed from their homes. According to the National Indian Child Welfare Association, more than half of adopted Native children in the United States today are placed outside their families, communities, and tribes. In 2011, NPR investigated and found that, despite the availability of licensed Native foster parents, 90% of Native kids in foster care in South Dakota were still placed in homes with non-Native families. Between 2010 and 2017, more than 1,000 Native children from one South Dakota county were taken from their families in placed in non-Indian homes. After intervening, the ACLU discovered that the child-custody and removal hearings often lasted fewer than five minutes with the state prevailing “100 percent of the time.” In 2020, the Minnesota Department of Human Services found that Native kids were found to be nearly 17 times more likely than non-Native kids to be removed from their parents.

Source: Mother Jones – In Minnesota, Native children account for more than 25% of the children in foster care, while only accounting for less than 5% of the state’s child population.

In response to these realities, tribes and child welfare organizations have advocated for ICWA’s protections to be strengthened and for more federal and state enforcement of ICWA’s processes. Advocates have advocated these reforms to state governments and to Congress in an effort to bolster the law’s protections. But since ICWA’s beginning, a growing consortium of powerful organizations and interests have been working to do away with the law entirely. Their financial motivations have been masterfully disguised behind their purported concern for the wellbeing and welfare of Native American children. Their efforts are beginning to pay off. The fate of ICWA now hangs in the balance, potentially resulting in the undoing of half a century of celebrated child welfare policy and reopening the door to harmful policies that could “return Indian children to the arbitrary and discriminatory whims of state courts and state agencies, unfettered by the centuries-old trust obligations this nation owes to Indian tribes and Indian peoples.”