The pervasiveness of consolidation in our everyday lives should not stifle the ability to imagine a society free from domination and an economy emboldened by open markets. Just as the current monopolistic status quo was purposefully constructed, so too can it be deconstructed.

In the context of merger law, the Supreme Court’s 1963 consideration of structural presumption in United States v. Philadelphia National Bank can be revived. Though it has been weakened by the more recent conservative movement in jurisprudence, the holding that a horizontal merger resulting in a firm with greater than 30 percent of the market share is presumptively illegal has not been formally overruled.

In Philadelphia National Bank, the merger under scrutiny produced market shares well above twenty percent, leading the Court to establish that exceeding this lower threshold could also be presumptively illegal. This presumption is balanced by the defendant’s ability to show business justifications to move forward with the combination of the merging parties.

The re-assertion of this existent standard would function as both a cleansing force in its simplification and a deterrent force. A study of this form of structural presumption of illegality found that they are extremely accurate in identifying anticompetitive mergers even under the efficiency standard.

Conduct specifically carried out by dominant or near-dominant firms can also be subject to a presumption of illegality. Justice Antonin Scalia, a critic of even the most permissive interpretations of antitrust law, recognized that the activities of a firm with substantial market power ought to be examined through a “special lens.” Scalia wrote in his dissenting opinion in Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Tech. Servs., Inc., “[b]ehavior that might otherwise not be of concern to the antitrust laws—or that might even be viewed as procompetitive—can take on exclusionary connotations when practiced by a monopolist.”

While pricing below short-term costs and exclusive dealing arrangements may have a passive effect on markets when conducted by non-dominate small firms, the nature of these business practices are of a drastically higher order of concern when achieved by dominant firms. A presumptive rule requiring the dominant firm to provide business justifications for these actions can be applied by the courts. Such a presumptive rule would mirror the European Union’s Abuse of Dominance law which imposes a presumption of illegality to conduct with potentially exclusionary effects undertaken by a dominant firm.

Despite the abundant resources of pro-monopoly interests, movements to oppose the monopolization of America and reform the system that promoted the relentless consolidation of markets are building momentum. A window of opportunity has opened up in recent years in which the status quo is increasingly questioned and challenged.

For Sally Hubbard, this moment in antitrust reform is not fleeting nor is its light dimming, “because it developed in response to widespread recognition that America has a monopoly problem. Until that problem is fixed, the American people will suffer a variety of harms, and the movement’s momentum will continue.”

“America has a monopoly problem. Until that problem is fixed, the American people will suffer a variety of harms, and the movement’s momentum will continue.”

One school of thought has prominently emerged to carry out the original intent of antitrust laws. The New Brandeisian legal movement sets out to resuscitate these existent laws and replace pro-monopolization dogma with an empirically informed project to build more fair and open markets. According to Miller, the new movement

“is against the centralization of economic power . . . . Our view is that we need to aggressively decentralize economic power to maintain checks and balances both within our economic system and between the private sector and the public sector. At the root of our vision is a robust innovative network of smaller, medium-sized businesses in markets in which there is a functional, competitive environment such that they are not competing on predatory terms but on terms that are more productive for society.”

The Biden Administration has welcomed scholars and lawyers that represent both a break and maintenance of the status quo, bringing hope that meaningful, tangible change can be enacted. While Biden’s appointment of Lina Khan to head the FTC was applause by anti-monopoly advocates, her leadership was also met by concerned Wall Street Journal editorials and fear-mongering from pro-consolidation forces.

Initially stymied by a gridlocked FTC with two commissioners appointed by Democrats and two appointed by Republicans, Chair Khan now has a newfound majority with the confirmation of Alvaro Bedoya. One example of the effect of this majority is in the shift in votes on the question of pharmacy benefit managers. In February 2022, the FTC voted 2-2 on initiating an investigation into whether pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are contributing to the decline in independent pharmacies and increased drug prices, meaning the investigation could not move forward. With the addition of Bedoya, tides shifted, and in June 2022, the FTC voted to launch the investigation.

Although the FTC has challenged mergers and acquisitions for their concentration harms upon which such dealings were abandoned, the expectation for impact and reform has increased now that Chair Khan leads a majority.

Biden’s appointment of Jonathan Kanter to lead the DOJ’s Antitrust Division established an anti-monopoly ally for Khan as well. Under their leadership, the FTC and DOJ are more inclined to provide updated merger guidelines to reform how the judiciary view cases involved mergers and signal to consolidated markets that further concentration will be scrutinized.

For Sarah Miller, revised merger guidelines are a priority among others because, “Corporations primarily amass market power through mergers, so revising and changing the guidance that the FTC and the DOJ developed is an important step to really putting a stop to the merger waves.”

In addition to new merger guidelines, Sandeep Vaheesan wants the FTC to “recognize that its power under Section 5 [of the Federal Trade Commission Act] is broader than the Sherman and Clayton Acts.” In practice, this “would mean a revival of norms of unfair competition then aggressively targeting things like below cost, pricing and tying, and exclusive dealing” as well as taking positions and articulating rules that impact workers more directly.

For Vaheesan, such positions include the FTC banning non-compete clauses and the FTC could restrict or prohibit some of the contractual methods of control used by new and old gig economy franchise models which would force companies like Uber to make a decision: either it treats its drivers as genuinely independent workers or it controls them as employees and also gives them the rights and benefits that come with employment.

Generally, anti-monopolists argue progress can be made if the DOJ and FTC articulates clear norms of unfair competition through policy statements, amicus briefs, and rule makings.

Hal Singer, managing director at Econ One Research and expert in antitrust has testified before Congress on various matters related to competition and antitrust enforcement. Singer sees the deficiencies in antitrust jurisprudence purposefully created to favor the accused corporation: “I learn about gaps in antitrust law when I see cases that I’m involved in fail and for no good reasons, but only just because a judge thinks that she’s hamstrung by existing precedent.”

“I see cases that I’m involved in fail and for no good reasons, but only just because a judge thinks that she’s hamstrung by existing precedent.”

For Singer, there are many “roads to reform” that can address these gaps: “one is that you bring new cases and you hope that you can get better law. The problem is that you have this installed base of judges who have been indoctrinated into the consumer welfare standard.”

The other avenue, the path Singer is advocating for is targeted, surgical legislative strikes. According to Singer, “The Court is not going to fix itself. If you want to fix it, you got to have a legislative strike.” Whether it is a “surgical strike that would put workers on equal footing to consumers under the law” or legislation that instructs the court to consider innovation harms or a bill to address the “clear gap in monopsony cases for no poach [agreements],” Singer views targeted legislative strikes as an essential road forward to reform. Critically, Congress can pass legislation nullifying that case law which has subverted the original intent of antitrust laws based on the inaccurate historical accounts and hollow economic theories.

Singer has testified before Congress in favor of a series of surgical legislative strikes targeted at dominant tech companies, including the issue of self-preferencing. He is a vocal advocate for the American Innovation and Choice Online Act, a bipartisan bill sponsored by Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa).

The legislation is targeted to only apply to the most dominant companies in tech. The bill would ban Big Tech firms from preferencing their products on their platform over the products of another business selling on their platform, prohibit the use of sales data of smaller companies operating on their platform to improve the sales of their rival products, require the platforms to be more interoperable, and curb excessive additional fees charged to smaller companies using these platforms.

Through the bill, the FTC and DOJ are provided a new tool to address anticompetitive practices committed by Big Tech. The bill has not yet received a vote from the full Senate. Singer argues that the agencies still ought to bring suits and provide new merger guidelines, but the law needs to change to adapt to contemporary challenges and improve the likelihood that such suits are successful.

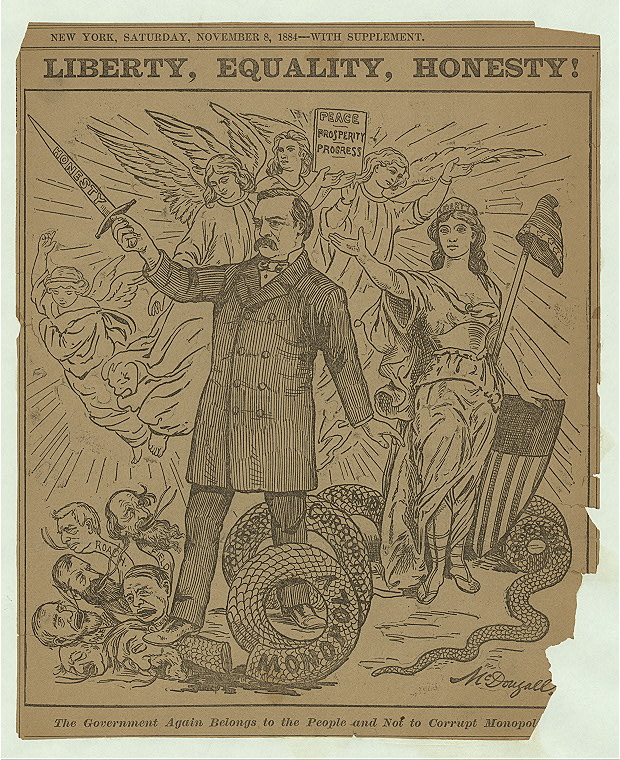

While contemporary technology and business practices would require contemporary solutions, much of the monopolization and resulting societal woes are subject to existent, yet subdued laws and jurisprudence. The once dormant antitrust agencies can be awakened to again function in their full capacity “like a court of equity,” prohibiting “not only practices that violate the Sherman Act and the other antitrust laws, … but also practices that the Commission determines are against public policy for other reasons.” Antitrust laws can once again be true to the egalitarian intentions of those who originally crafted them.

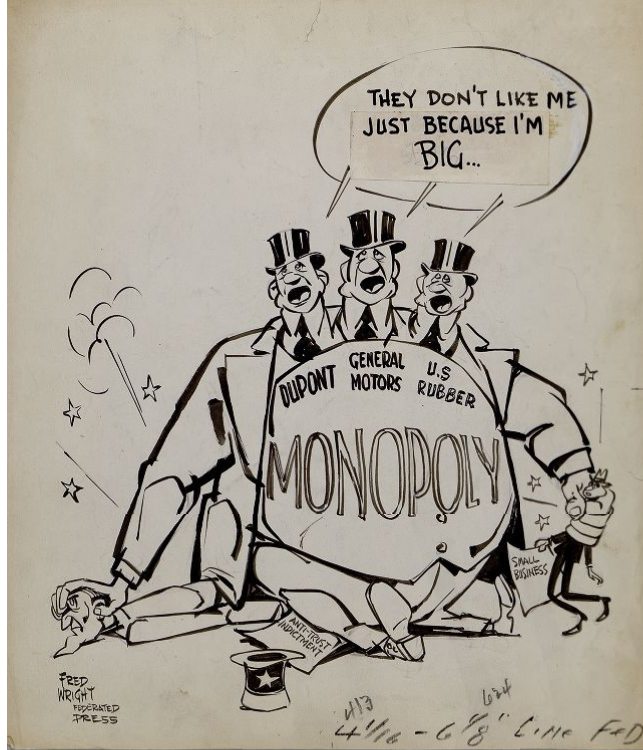

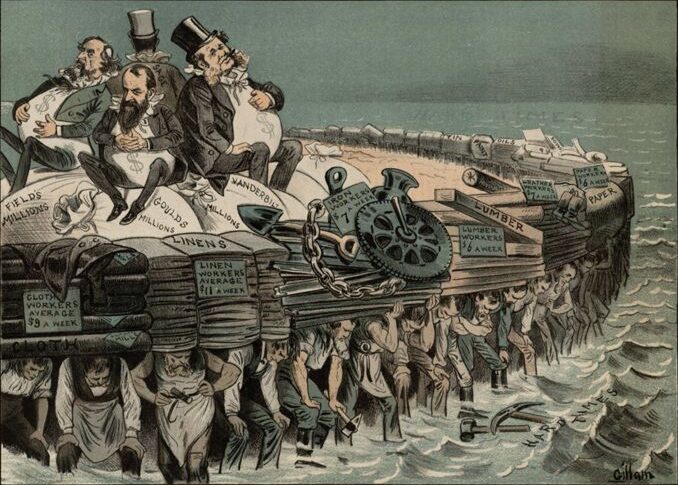

The pressure to act is mounting. A survey of American Economics Association members shows growing consensus and strong agreement that antitrust laws should be “enforced vigorously.” A majority of Americans now support aggressive antitrust enforcement: parents who were desperate and unable to buy baby formula; farmers who are being pushed to the edge of extinction by big agriculture; entrepreneurs; small business owners whose home-grown business failed after their products were replicated by Amazon and sidelined by the platform’s self-preferencing; stifled entrepreneurs and STEM PhDs who will opt to join a dominate firm rather than grow a high-tech, high opportunity start up; the working class being paid 20 percent less in a concentrated labor market which hinders their economic freedom.

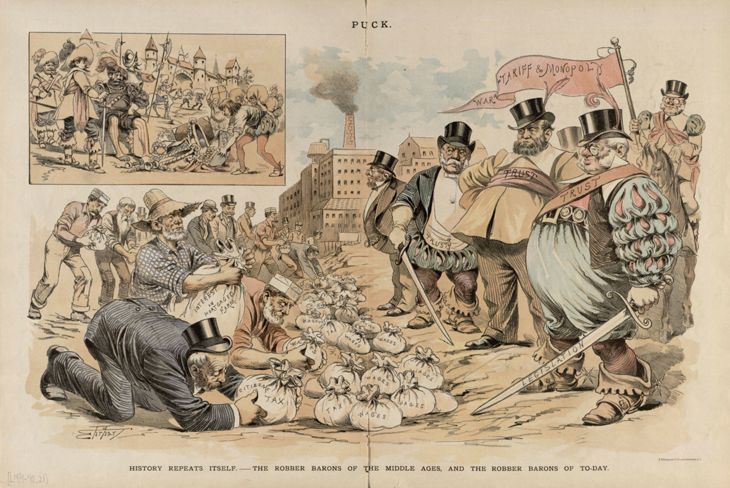

In the fragility of our supply chains, baby formula crisis, price increases, poor working conditions, threats to our democracy, and every cable, health, and grocery bill, the public may soon recognize the costs of monopolization and grow weary from bearing the burden of autocracy in our economy. As Senator Sherman said in 1890, “If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation and sale of any of the necessaries of life.”

“As Senator Sherman said in 1890, “If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation and sale of any of the necessaries of life.”

Antitrust enforcement establishes a system of political economic checks and balances such that the citizen is centered in the economy and free of economic domination. We need only to choose to employ it. Our present condition is simply the result of an absence of will in the face of democratic and economic erosion. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote, “We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot have both.”