The Business of Probation

Missouri Outsources Justice to For-Profit Firms

Lucy Sun

August 23, 2025

On a late-night fast-food run in March 2013, Jason DeFriese was pulled over for speeding. The officer suspected the college junior had been drinking and asked him to take a breathalyzer test. Jason refused, remembering the advice from a family lawyer.

The officer arrested him on the spot, charging him with speeding and — because Jason had refused the test — an automatic DUI.

At Jason’s hearing in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, the court dismissed the speeding charge. He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor for driving while intoxicated, and the court placed him on probation under a “suspended imposition of sentence.” If he complied with the terms of his two-year probation, he would avoid jail time and leave without a conviction on his record.

Jason paid $418 in court costs and another $310 in assorted fees. As part of his probation, he was also required to abstain from drugs and alcohol, complete a substance abuse traffic offender program, perform 40 hours of community service, and install an ignition interlock device on his car for nine months — at a cost of just over $1,000.

But that wasn’t all. His compliance wouldn’t be monitored by the state. Instead, it was outsourced to Private Correctional Services, or PCS, a private probation company. Jason would have to report to PCS each month and pay them for periodic drug testing and whatever additional fees the company imposed.

A few months after his probation began, Jason graduated from college and moved home to St. Louis. He started working at a fitness center in the city. Despite the move, PCS required him to report to their office in Cape Girardeau. They refused to let him report to a local agency. Once a month, he drove two hours south to their office.

Photo by Jimmy Emerson. Source: https://flic.kr/p/Bhcmgp

Eight months into probation, PCS’s grip tightened. They administered a random drug test, and Jason tested positive for alcohol. Jason insisted he hadn’t been drinking. The trace amount, he explained, could easily be the result of exposure to alcohol-based cleaning solutions at his job or the alcohol-based hygiene items, like mouthwash, cologne, or hair gel, that he used. He pointed out that the level was so low that the state-run lab wouldn’t have flagged it as a violation.

The judge wasn’t convinced. He warned Jason that another violation would mean jail. Then, on the very day of his hearing, PCS demanded another urine sample. Jason tested positive again. He asked for another test. PCS refused. Alarmed, his father rushed him to a private lab for an independent retest. The results came back negative, but it didn’t matter.

Jason’s conviction went on his record. He served four days in jail, paying $90 in boarding fees and a $500 fine. For 90 days, he wore an alcohol-monitoring bracelet — installed and managed by PCS at $91 per week. Every week, he drove two hours back to Cape Girardeau so PCS could download the data. PCS also placed him in an intensive drug testing program, requiring him to call in every morning to see if he’d been selected for testing. If chosen, he’d have to make the same two-hour drive that day.

What was meant to be an alternative to incarceration becomes a long-term financial burden, where every drug test, ankle monitor, and check-in is another opportunity for profit extraction.

The constant call-ins and surprise trips made it impossible to hold down a job. Eventually, Jason resigned from the fitness center because he couldn’t keep asking for time off to take a drug test.

His probation finally ended in October 2017. Over its course, he took 68 drug tests for PCS, all negative. His family spent $10,801 on those tests.

Looking back, Jason wonders where he’d be if he hadn’t been forced to quit his job. But he knows he was luckier than most. He had his family’s support. “I was thinking about other people,” he said. “How would other people do it?”

Stories like Jason’s are not uncommon in Missouri. While the Department of Corrections supervises individuals on felony probation, state law prohibits it from supervising most misdemeanants. As a result, many local courts have turned to private companies to run their probation services. In fact, Missouri statute expressly authorizes circuit judges to contract with private entities to “provide probation supervision and rehabilitation services for misdemeanor offenders.”

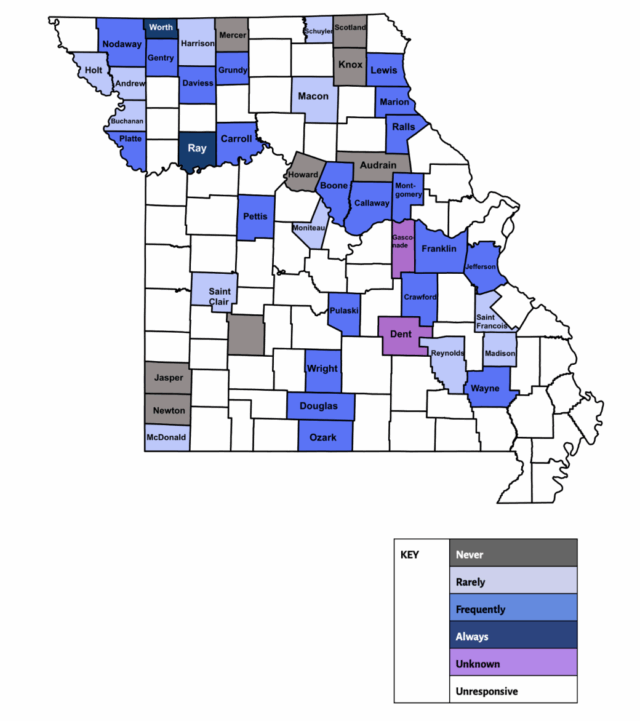

Missouri is one of at least a dozen states that allow private probation. But because of its decentralized and opaque local court system, it’s not clear exactly how many of Missouri’s 37,000 probationers are under private supervision. What seems quite clear, however, is the pervasiveness of this arrangement across the state. In a 2022 statewide survey by Empower Missouri, 35 of the 45 responding Circuit Court Clerks reported contracting with private companies for misdemeanor supervision. Over half acknowledged relying on their services “frequently” or “always.”

“Private Probation Practices by Frequency of Use Across Missouri Counties.” Map by Empower Missouri.

It’s an attractive arrangement for these courts. They receive a portion of the supervision fees paid by probationers without expending a single resource of their own. Local newspapers regularly publish judges’ solicitations for proposals from private probation companies. These solicitations don’t go unanswered. “You’ve Come To The Right Place,” one such company proclaims on its website. “The purpose of Supervised Probation Services is to provide supervision of misdemeanor offenders[,] giving a court sentencing alternatives without burdening the clerical staff.”

It’s also an attractive arrangement for companies like Supervised Probation Services. Beyond pocketing most of the monthly supervision fees, they can require probationers to submit to random drug tests, electronic monitoring, and other so-called “compliance” services — all of which come with additional fees that go straight to the company.

Rather than invest in reform, however, state and local governments devised ways to make the system pay for itself.

But this arrangement comes at a steep cost — not for the courts, and not for the companies, but for the probationers. For people like Jason, the charges add up fast, and so do the consequences of potential violations. What was meant to be an alternative to incarceration becomes a long-term financial burden, where every drug test, ankle monitor, and check-in is another opportunity for profit extraction.

Those caught in the system’s greatest depths — people without financial resources or support — find themselves in a cycle of debt and surveillance far more violating and punishing than their original offense ever warranted.

This is the private probation system in Missouri today: a sentencing alternative that now serves the courts’ convenience, corporate profits, and little else.

A Period of Proving

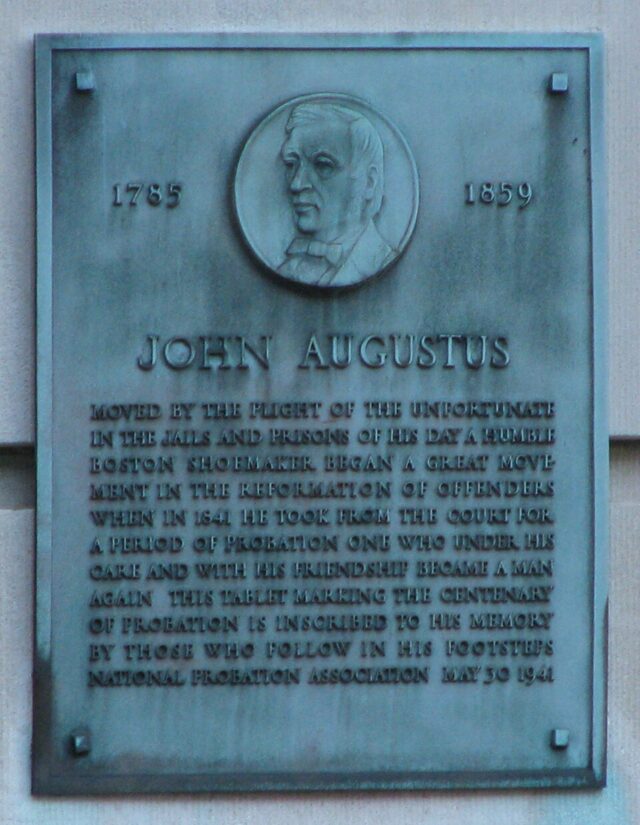

The American concept of probation is said to trace back to a summer morning in 1841, when Boston cobbler John Augustus watched a ragged man brought before the court for public drunkenness.

Something in the man’s earnest pleas moved Augustus. He persuaded the judge to release the man into his custody for three weeks.

When Augustus returned with the man for sentencing, his transformation was remarkable. According to Augustus, the change was so profound that no one in the courtroom recognized the man. The judge, impressed, imposed only a fine of one cent plus court costs.

“The man continued industrious and sober, and without doubt has been by this treatment, saved from a drunkard’s grave,” Augustus later wrote.

Encouraged by the man’s transformation, Augustus went on to bail out nearly 2,000 men, women, and children. It became a practice in the court that people charged with public drunkenness could be released under supervision, and if they demonstrated reform by the end of the period, their penalty would be reduced to a symbolic fine.

Augustus sheltered many of these individuals in his own home. He secured work for them and guided their rehabilitation. Among his first 1,000 cases, he reported just one bond forfeiture. He called his approach “probation,” derived from the Latin “probatio,” — a period of proving.

Plaque honoring John Augustus in Boston. Photo by Tim McCormack.

Massachusetts enacted a statute that formalized Augustus’s practice in 1878. It was the first to use the word “probation,” and it authorized the mayor of Boston to appoint a probation officer as part of the police force. Other states soon followed Massachusetts’ example. By 1956, every state had passed legislation authorizing probation as an alternative to incarceration.

Rise of Private Probation

For more than a century after Augustus, probation remained firmly within the public sphere. But by the 1970s, the country’s criminal justice systems were buckling under the weight of the era’s “tough on crime” policies. As prison populations soared, so too did the number of people under correctional supervision.

“These people needed supervision, and there wasn’t anyone supervising them,” said Associate Circuit Judge David C. Mann. It was 1992, and he was responding to scrutiny over his new arrangement with a bail bondsman who had established a private probation service, rent-free, in a space leased by the judge.

The peculiarities of Judge Mann’s deal aside, his comment reflected an underlying reality: a system that was overwhelmed and underfunded.

By the 1970s, government reports had already labelled probation a “system in crisis.” The National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice found probation services nationwide “not adequately structured, financed, staffed, or equipped with necessary resources.” And the Comptroller General warned bluntly, “If no action is taken, probation systems will continue to be overburdened and will deteriorate further, increasing the dangers to society.”

Rather than invest in reform, however, state and local governments devised ways to make the system pay for itself.

They unleashed a barrage of surcharges on defendants: fees for arrest, processing, clerk services, jail boarding, even applications for a public defender. In Cape Girardeau County, Missouri, for example, judges routinely extracted $150–$300 from misdemeanor defendants for the “Cape County Law Enforcement Restitution Fund.”

As budget constraints tightened, a number of states and local governments also turned to fines and fees for minor offenses and traffic violations. Some went further, implementing mandatory penalties that eliminated judicial discretion entirely.

This practice was on clear display in Missouri. In 2015, the small town of Pagedale came under fire when residents sued, alleging the city’s dependence on fines and fees violated their constitutional rights. In 2013 alone, Pagedale’s municipal court — serving just around 3,000 residents — heard 5,781 cases, an average of 241 per court night. Residents were fined under local ordinances for “not having curtains on their basement windows, having mismatched blinds, having more than three people at a barbecue, and having a basketball hoop in the front of their house.” These fines had become the town’s second-largest source of revenue.

Naturally, this reliance on an “offender-funded” model isn’t limited to traffic tickets and local code violations. The same logic — shifting the costs onto those caught in the system — had already begun to reshape probation decades earlier.

The idea of outsourcing probation to private companies swept through courthouses in the 1990s. An owner of one such company in Georgia explained to the Atlanta-Journal Constitution that, “Most cities can’t afford their own probation department. There is no cost to the city or taxpayers. So far it’s paid off. We keep a lot of judges happy.”

Another in Chatham County, Georgia, told the newspaper that his firm “should save $365,000 a year in expenses, and it may even bring more revenue into county coffers.” Both he and county officials agreed that “because the financial livelihood of the private company depends on the collection of fines,” the company “will be more aggressive and successful in collecting fines than state and county officials have been.”

Around the same time, Missouri legislators similarly embraced the cost-saving and possibly profitable scheme. The state codified private probation into law, granting circuit judges the authority to enter into contracts with private companies for misdemeanor supervision.

The statute passed with little fanfare, and in another context, its impact might have been limited. But several factors may have created ideal conditions for privatization to take root and spread throughout Missouri.

To begin, the state’s Board of Probation and Parole is statutorily barred from supervising most classes of misdemeanor offenses. This prohibition, shaped in part by long standing budgetary concerns, leaves courts to manage supervision without state support.

In rural areas, the lack of alternative services only deepens the problem. “For people that are struggling with criminal justice involvement in rural counties, there’s nothing, except maybe a faith-based recovery center if you’re lucky,” says Gwen Smith-Moore, Criminal Justice Policy Manager at Empower Missouri. “Those courts don’t have the same ability to partner with local agencies to offer services that cities do.” Without support from the state or other resources, judges turn to private companies to fill the gap.

But it’s not only what Missouri law prohibits — it’s also what it fails to regulate.

Oversight of private probation companies is minimal from the outset. Just three statutes govern the contracting process. One directs judges to consider a company’s qualifications, including experience in supervising, financial capacity, “and other factors as the judges deem necessary and relevant.” Another bars judges from contracting with companies in which they or their relatives have a “material financial interest.” And the third outlines basic procedures for soliciting proposals and sets a minimum contract term of three years.

In practice, these sparse requirements offer courts little guidance, leaving them to develop their own standards. When asked about Judge David C. Mann’s decision to partner with a local bail bondsman for probation services, the bondsman responded, “What’s he supposed to do, hire somebody he doesn’t know? Somebody he doesn’t like?”

And once a company secures a contract, it operates with virtually no transparency. Unlike states such as Tennessee, Missouri doesn’t have an independent oversight board to enforce professional standards or monitor these companies’ practices. Nor does it maintain a public list of providers, as Georgia does. In fact, Missouri has never even conducted a systematic accounting of how many private probation companies are operating in the state. It’s as if a private probation system doesn’t exist at all.

Rural Missouri. Photo by Jimmy Emerson. https://flic.kr/p/dRJ9Tj

The Business of Violating

Behind the veil, however, are real people caught in cycles of debt, surveillance, and even incarceration. It’s the inevitable result of an industry that must extract money to survive.

This is precisely what makes private probation so troubling. Beyond the lack of regulation and transparency, its business model creates a perverse incentive structure. Companies generate revenue when they collect fees from probationers. Every person who completes probation is a lost source of revenue. As a result, these companies need a supply of probationers, and they need them to stay in the system.

The revenue-generating process begins with a simple first step: secure a steady supply of clients. Some private probation companies embed themselves directly into the courtrooms to do just that. As Tony Messenger of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch observed in Dent County: “Everyone who appears before [Associate Circuit Court Judge] Baird and bonds out of jail or pleads guilty ends up on a form of probation with the privately operated MPSS. [Private probation officer] Blackwell isn’t elected, but she has her own chair in Baird’s courtroom, right next to the prosecutor.”

In other places, the client-acquisition tactics may take more covert forms. Smith-Moore recounts an interview with a judge from another county. The judge described private probation companies offering incentives to attorneys for client referrals: “Refer your clients to us and we’ll give you Cardinals tickets.”

Once companies secure these clients, the revenue stream begins. While Missouri caps the monthly supervision fee at $60, there’s a whole slew of other fees companies can collect.

“They can make you take drug tests every week, they can make you do 250 hours of community service, they can make you wear, maybe, electronic equipment. In other words, probation can make you do things and restrict movement and activity.”

For example, a court may order a defendant to complete an anger management course as a condition of probation. The private probation company overseeing her case will then require her to enroll in their course, all at her own expense. This might cost up to $800, with no clear limit on how many sessions she must attend.

It’s also not uncommon for courts to require defendants to submit to weekly or biweekly drug tests as a condition of probation, even when the underlying offense had nothing to do with substance use. In that case, the private probation company provides the drug tests at a cost of $30 each.

Testing positive, missing a test, arriving late, falling behind on payments, or failing to comply in a multitude of other ways can be deemed a probation violation — and that, too, is a profit opportunity. In Missouri, private probation companies receive payment for violations issued, creating an incentive for companies to closely monitor probationers’ every move.

As one state probation officer described, “There is a limit, but how they get around it . . . let’s say for example a guy is on probation for petty larceny. What private probations do, they say okay . . . you have to do drug screen, and you have to do drug screen through us. And they add on all these additional services that the client is responsible for. And if the client doesn’t partake in that stuff then they’re in violation of their probation. And the next thing you know, they’re going back to court.”

Once back in court, the private probation officer may testify to the violations. The judge, perhaps following the officer’s recommendations, may then extend the probation period and impose new conditions. These new conditions may conveniently require more classes, more tests, and more fees.

Recall Jason, who refused a breathalyzer test and was arrested. After failing a drug test administered by his private probation officer — a test the officer refused to let him retake — the court adopted the officer’s recommendation: 90 days with an ankle monitor, installed and managed by the same private probation company, at a cost of $91 per week or $1,183 total. And that pales in comparison to the $10,801 his family paid for the 68 drug tests the company required under its intensive drug testing program, another consequence of the violation.

Alternatively, the court may send the probationer to jail. Perhaps under the recommendations of the private probation company for “shock time.” Even there, the company can continue to extract fees

That’s exactly what happened to Jerry Swartz. After being charged with a DWI in 2014, the court placed him under the supervision of private probation company American Court Services. Under Missouri law, ankle monitors are reserved for people with multiple DWI convictions. Schwartz had no convictions. Nonetheless, he was required to wear one. When he was later jailed for alleged probation violations, he was ordered to keep the device on — paying the company for its use while behind bars.

“Private probation companies are trying to violate their clients,” Swartz said. “That’s their business model.”

However, Swartz and Jason both acknowledge they were more fortunate than most. They paid, and they could afford to do that. For many others trapped in the system, getting out seems impossible.

![[F]law School Episode 12: The Body (S)camera](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/POOKKULAM_HERO-e1728232922783-640x427.jpg)