In contrast, section 8 units can receive repair and improvement services from their private landlords or management companies. As they receive payments from their tenants and the government through voucher subsidies, they are often able to receive market-rate rent and thus have the funds to make repairs when they are needed. Though it is not always the case that these repairs are made when needed, private owners are still in a better position to make necessary repairs and improvements than housing authorities that operate solely on their funding from HUD and the limited rent payments they receive from their tenants. Recognition of this distinction led to the start of a new approach to public housing operations in 2012.

RAD

The Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD), enacted as part of the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, is a federal housing program initiated by HUD in 2012 to “give public housing authorities a powerful tool to preserve and improve public housing properties.” It does so by providing a pathway to convert public housing units into project-based section 8 housing units. Under this program, housing authorities can access section 8 subsidies (which are comparatively better funded than public housing subsidies) and even outsource ownership and/or management of redeveloped units.

They are also able to access the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program (LIHTC) to fund redevelopment if they bring in a nonprofit or for-profit partner to manage the tax credits.

Perhaps most importantly, RAD allows public housing providers to access these resources without privatizing their buildings, meaning that housing authorities are not required to transfer their control to take advantage of the program. In fact, these conversions can lead to a variety of ownership structures, with some housing authorities retaining control or managing the buildings through nonprofit subsidiaries, others entering into joint partnerships with private entities, and the rest being fully transferred to private owners.

Regardless of the ownership structure adopted, tenants of RAD converted units are guaranteed the same protections that they enjoyed when they were public housing tenants. These include the right to participate in self-organized tenant associations, the right to pay no more than 30% of their adjusted income in rent, and the right to grievance procedures, all of which are retained after a conversion. Additionally, after living in the converted property for a certain period of time, a resident has the right to request a tenant-based voucher to move from the property and rent a unit elsewhere. This focus on tenant protections is a unique feature of RAD when compared to previous public housing revitalization efforts by HUD, such as HOPE VI which resulted in the displacement of tens of thousands of public housing renters.

“I consider RAD to be a stop-gap measure,” she said, “it’s what happened when HUD was trying to figure out what to do with the fact that Congress would not fund public housing sufficiently.”

While attitudes towards the program vary, a common sentiment is that RAD was the best achievable option for our public housing situation at the time of its passage. This seems to be the view expressed by Miriam Axel-Lute, co-CEO and editor-in-chief of ShelterForce, a nearly 50-year-old nonprofit publication that covers the worlds of community development, affordable housing, and neighborhood stabilization. “I consider RAD to be a stop-gap measure,” she said, “it’s what happened when HUD was trying to figure out what to do with the fact that Congress would not fund public housing sufficiently.” When asked about the factors she believed led to the creation of RAD in 2012, she responded:

“There was a real crusade from within the affordable housing community to do something [about the deterioration of public housing]. And … the first several proposals were much more concerning than RAD in terms of privatization. They actually were privatization in many ways. They didn’t have nearly as many protections as RAD did … At the time, it seemed like the drive was largely coming from folk’s saying, ‘alright, if you won’t fund public housing, what will you do? What can we do about this because these units are falling apart.’”

RAD and Funding

To proponents of RAD, the program is an efficient way to acquire the investments necessary to make desperately needed repairs. These advocates understandably believe that it is better for housing authorities to sacrifice the status of their buildings as public housing than to continue to allow their units to deteriorate. However, this viewpoint is silent on the most obvious solution to the backlog of repairs and improvements: provide more funding to public housing subsidies. While simple, this action would need to overcome an over 40 year trend of disinvestment in affordable housing.

In 1978, HUD’s budget was over $83 billion (in 2004 constant dollars). This level of funding reflected the federal government’s commitment at the time to building, maintaining, and subsidizing affordable housing. These priorities changed in 1981 when Ronald Reagan took office and began the process of dismantling social programs designed to assist the poor, including the federal funding of affordable housing production.

By 1983, HUD’s budget had fallen to little more than $18 billion (in 2004 constant dollars), barely more than one-fifth of its previous level. This dramatic reduction had a substantial impact on the work the department could perform, exemplified by the fact that in the 6 years between 1976 and 1982, over 755,000 new public housing units were built but in the 24 years between 1983 and 2007, only 256,000 units were built by HUD.

These cuts have only continued, leading to the construction of fewer public housing units as well as the continued deterioration of existing units. This consistent lack of funding has exacerbated the issues, as repairs that may have been relatively cheap to make when first needed have only gotten worse over years of waiting and may require invasive, expensive work today. Even when efforts are made to fund these repairs, such as the Build Back Better bill which would have provided $65 billion to address unmet renovation needs in the nation’s public housing stock, there never seems to be enough political will to adopt such proposals. As a result, the barrier to repairing our public housing stock has just grown more insurmountable.

Part of the appeal of RAD is that it doesn’t require any additional direct investment into the housing programs. It is “revenue-neutral,” as it just converts the kind of subsidy being used and could thus be employed without requiring a change in funding practices.

Though this model may create issues down the road as more units rely on section 8 subsidies and more funding is required to ensure that the program can adequately meet the needs of its constituencies, it currently allows HUD to fund its unit repairs without having to rely on the minimal public housing budget. In this way, Congress can continue to avoid providing additional funding to affordable housing while saying that they are doing something to address the deterioration of public housing.

Why Do We Fund Section 8?

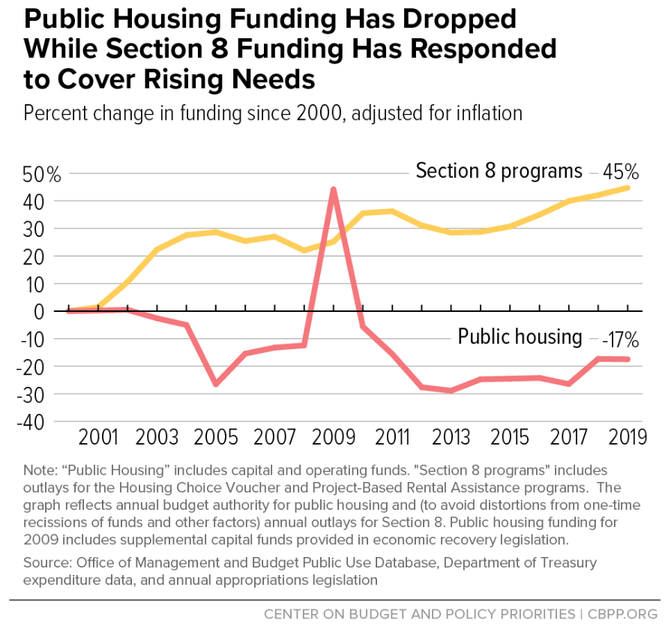

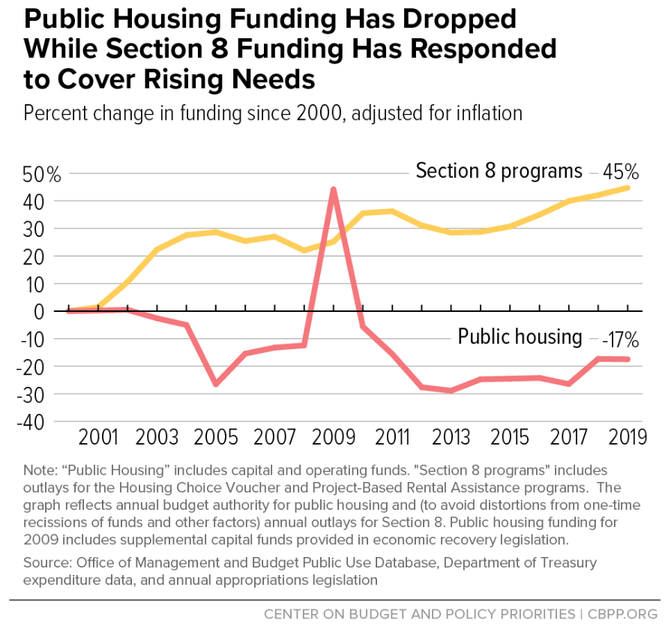

The main reason RAD works is Congress’s consistent funding of section 8 subsidies. Though far from what is needed to tackle the affordable housing crisis, section 8 voucher programs generally receive the lion’s share of HUD’s yearly budget allocations and have for a number of years. According to data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, from 2000 to 2019, funding for public housing dropped 17% in inflation-adjusted terms while section 8 funding increased by 45% in inflation-adjusted terms within that same period. If both subsidies are meant to provide assistance to low-income tenants, why is there such a gap?

Public Housing and Section 8 Programs Percent Change in Funding Since 2000

Alex Schwartz, a professor of public policy at the New School, attributes the difference in part to who relies on the programs. “Public housing doesn’t have the constituency of project-based section 8, it doesn’t have private developers who will be going into default [if payments aren’t made] and the banks that would have trouble…. [I]n public housing, [underfunding] just leads to decline and crumbling of the physical structures and suffering on the part of the tenants.” In other words, when public housing is underfunded, the only ones harmed are the tenants, whereas when section 8 is underfunded, there is a whole network of mostly private entities that may be affected. This dependence has been enough to ensure that section 8 subsidies receive relatively adequate funding, at least compared to their public housing counterpart. The subordination of tenant’s interests to those of private developers and the banks that lend to them seems to reflect a prioritization of business interests in Congressional funding policies that further explains the discrepancy.

When public housing is underfunded, the only ones harmed are the tenants, whereas when section 8 is underfunded, there is a whole network of mostly private entities that may be affected.

Another reason often cited for this funding gap is the stigma surrounding public housing. While most Americans favor efforts to address housing insecurity and believe that Congress should prioritize legislation to grow the housing supply and make housing more affordable, their support tends to waver when such developments are proposed in their communities. A phenomenon colloquially referred to as NIMBY, or “Not In My Backyard,” people’s attitudes towards affordable housing developments can change dramatically when they occur in their local area. These sentiments, and the oppositions to affordable housing developments they inspire, have been said to be based on the “assumed characteristics of the population that will be living in the development,” with common arguments asserting that these developments will bring “increases in crime, litter, theft, violence and that property taxes will increase.”

The sources of these assumptions implicate a number of other racial and socio-economic biases that are deeply rooted in our nation’s housing history, but in their current form they have the effect of producing a clear stigma against public housing tenants and the buildings in which they reside.

As a result of this stigma and the characterizations that accompany it, public housing residents can experience a form of social and economic isolation that signals their differentness from “normal” society and makes it easier for others to ignore their struggles. In Axel-Lute’s view: “We hate public housing in this country so much because we’ve racialized it and we’ve isolated it. It’s the thing into which we pour our guilt about treating the poor badly and not having a good housing system.”

All of this is not to say that section 8 subsidies have no stigma attached to them, but the decentralized nature of voucher recipients and the complexity of governmental voucher programs is often helpful in shielding the program from the same kind of negative assumptions. “People don’t even know what [section 8] is,” says Schwartz, “even though it’s a bigger program than public housing in terms of total units, it’s pretty obscure and in the weeds and bureaucratic.”

Thus, when legislators are allocating funding to governmental housing programs, they are more likely to fund the program that their constituents don’t stigmatize as strongly and that has the benefit of supporting the interests of private entities.

Concerns with RAD

While fulfilling their role of providing funding for necessary repairs and improvements, RAD conversions bring their own issues into the subsidized housing market. One of these issues relates to the rights of tenants in RAD converted buildings.

As previously mentioned, resident’s rights as public housing tenants are supposed to be retained when their units are converted to section 8.

However, there is concern that the lack of housing authority oversight of private management companies that take over some buildings can lead to violations of these rights. In support of this view, advocates have pointed to preliminary evidence showing rising evictions in New York City Housing Authority units after their conversions. At this point, it is too early to draw conclusions about the general influence of conversions on eviction rates, but this data is worth considering.

Another concern often raised by tenant advocates about RAD conversions is that they open the door for private management companies to eventually convert these section 8 units to market-rate units at the end of their contracts. This is a common practice among owners of existing section 8 units and one that RAD attempted to avoid by requiring that converted units enter 20-year contracts that automatically renew for another 20 years at the end of the term.

Since RAD began in 2012, none of these units have yet reached the end of their contracts, but the concern is that once the first term ends, owners may want to pull out of the program due to market changes or other factors. Were this to happen, it is uncertain if the renewal provision of the contracts would be held to be enforceable and the stock of affordable housing may plummet even more.

Housing authorities are increasingly converting their public housing stock to section 8 units, funding is likely to continue growing for these subsidies and falling for public housing.

An argument could be made that these issues only apply to converted units that are no longer managed by a public housing authority and could thus be avoided by encouraging these housing authorities to continue managing these properties. While this is true to an extent, the use and growth of RAD conversions, even by public housing authorities that retain control, presents a more systemic problem.

If housing authorities are increasingly converting their public housing stock to section 8 units, funding is likely to continue growing for these subsidies and falling for public housing. As a result, public housing buildings would be pushed to convert if they wanted to access adequate funding and the remaining public housing stock would consist of buildings that could not be converted because their conditions are so bad that not even section 8 subsidies or tax credits could attract developers to address their needs.

In a previous interview, Schwartz analogized this to the health insurance pool “where all the healthy people leave, and then you’re just left with those who have the most expensive health needs.” Left unchecked, these factors could lead to the end of modern-day public housing and the establishment of a system where affordable housing is almost entirely a private realm.

![[F]law School Episode 7: Profit Over People](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Housing-Podcast-Episode-hero-image-640x427.webp)