The Innocent Victims of the Dopamine Economy

How corporations use children’s developmental vulnerabilities to create life-long consumers.

Gauri Sood

July 7, 2025

A Neanderthal returns from his hunt to express an unspoken pitch. He tosses the catch at the feet of his family, then grunts with pride, raising it to the firelight, and then gesturing toward its size. From these moments, a primitive form of marketing was born, composed of early humans exchanging goods and favors. In those kin-based communities, the “consumer” was intimate and familiar, and the stakes were survival, reputation, and belonging.

But by the 1920s, the stake of appeasing a population increased, as rapid industrialization raised the sheer amount of public consumption of corporation-produced goods. An increase in “consumer-oriented businesses,” or corporations targeting their products for specific populations, was the side effect of this booming, innovative economy. Corporations now no longer knew their customers personally, but still needed to persuade them.

Advertising Across the Decades

Corporations began investing their resources to intimately get to know their audiences, and advertising skyrocketed. To do so, they moved beyond simply matching their consumer preferences, and started trying to actively shape them. Advertising progressed rapidly from a tool that reflected the people’s desires, to an instrument that influenced and changed them.

Corporations hired psychologists and other experts in an eager hope to better understand the behavioral mechanisms of their consumer base. When companies began this behavior-focused marketing race, obtaining and keeping their users’ attention became of utmost importance, and marketing became more about manufacturing the user’s demand instead of solely meeting it.

In the 1920s and 1930s, General Motors (GM) overshadowed Ford’s dominance within the American car manufacturing industry. This automobile takeover by GM, led by Alfred Sloan at the time, was a clear example of the sharp increase in targeted advertising. During the Great Depression, the consumer base for cars was significantly poorer. GM recognized and capitalized on that knowledge by allowing consumers to utilize car financing and by shifting its production to Chevrolet, a high-volume affordable brand.

As neuroscience and psychology research into dopamine and its connection to pleasure grew, the marketing industry shifted forever, now tailored to not only our behavioral mechanisms but also our neural processes.

The end goal for the corporation was, as always, profit maximization. And by building a base of loyal consumers, GM established the promise of lifetime customers, rather than one-off sales, guaranteeing decades of profits.

Fast-forward 100 years to today’s economic landscape, where advertising finds its consumer-targeted success in neuroscience, a field intertwined with parts of psychology. “Anticipation is marketing gold — and dopamine is the currency that leads to a richer bottom line,” writes a columnist at MarTech, a digital publication on marketing technology. As neuroscience and psychology research into dopamine and its connection to pleasure grew, the marketing industry shifted forever, now tailored to not only our behavioral mechanisms but also our neural processes.

The Function of Dopamine

The rush of dopamine is a familiar feeling; a normal surge of pleasure, joy, perhaps intense excitement. You might anticipate meeting someone; look forward to exciting weekend plans; or are surprised by a promotion you didn’t think you would get. These moments of unexpected reward stem from this neurotransmitter, one of the few that powers the positive emotions emulating from our brains.

Dopamine does more than drive our happiness. It’s the backbone of our reinforcing behaviors. And the slope between reinforcement and addiction is a slippery one. As discovered and researched by Dr. Roy Wise, now a Senior Investigator at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, dopamine plays a central role in anticipation and motivation to seek rewards. This dopaminergic-driven motivation is the root of all addictive behaviors, including gambling, substance abuse, tobacco consumption, and most recently, technology use. The brain’s all-encompassing focus on the anticipation of drugs, or other rewards, is a “hijacked brain,” taken by the motivating drive for more and more and more.

Social Media, Variable Rewards, and Addiction

Social media has now been scientifically proven to engage the same dopaminergic circuitries as cocaine, though one is a criminalized substance, and the other flows freely. Surely, for social media companies to understand the presence of this neurotransmitter and its related processes is not enough to hook a user. And indeed, technology giants like Meta and others have moved past a thorough understanding of what kinds of mechanisms can grab adolescent consumers, and into what will keep them addicted.

Social media platforms share a technique with slot machines — the mechanism of variable rewards. These are uniquely unpredictable, which creates a sense of anticipation within the user. Indeed, companies manufacture intermittent rewards by waiting to send through a user’s notifications at all before releasing several at one time. This increases the strength of the reward, fueling the consumer’s dopaminergic reinforcement system.

By refraining from releasing all of the user’s reward all at once — the likes, comments, and views — the unassuming consumer remains eagerly waiting, frequently checking their phone, repetitively reactivating the same networks that light up when they pick up their device. Meanwhile, subtler mechanisms, such as endless scrolling opportunities, auto-play on Netflix and YouTube, and the ability to “tag” friends on platforms work to increase constant engagement and simultaneously decrease the ease of exiting an app.

Recent statistics show that these tactics are working. Over 33 million Americans, or roughly 10% of the U.S. population, report feeling addicted to social media. Teenagers and young adults (between ages 18-22) make up roughly 40% of this group. Yet, an even larger percentage of addicted individuals are also the most vulnerable; over one-third of girls ages 11-15 reported feelings of addiction.

There is a scientific reason as to why children report greater levels of addiction, and that isn’t merely the inextricably tight link between technology and the everyday lives of younger generations. In fact, the reason extends beyond even the growing presence of youth-targeted media, or the large amount of time they spend on Snapchat, Instagram, and other social media apps. Instead, it is precisely in the neuroscience of the developing brain.

The Vulnerabilities of the Developing Brain

Dr. Judith Edersheim, the Founding Co-Director of the MGH Center for Law, Brain, & Behavior, explained that children are particularly susceptible to addictive behaviors and reward-driven engagement due to differences in three main brain areas.

“There are gray matter changes, there are white matter changes, and there are neurotransmitter changes,” she noted. The limbic system of our brain is focused on emotion and reward, and during adolescence, it is a highly developed system. This means our tendency to seek rewards is in sufficient operation throughout adolescence. However, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and overall frontal lobe, which are areas involved in executive functioning, decision-making, and emotional regulation, are underdeveloped.

Dr. Judith Edersheim, the Founding Co-Director of the MGH Center for Law, Brain, & Behavior, explained that children are particularly susceptible to addictive behaviors and reward-driven engagement due to differences in three main brain areas

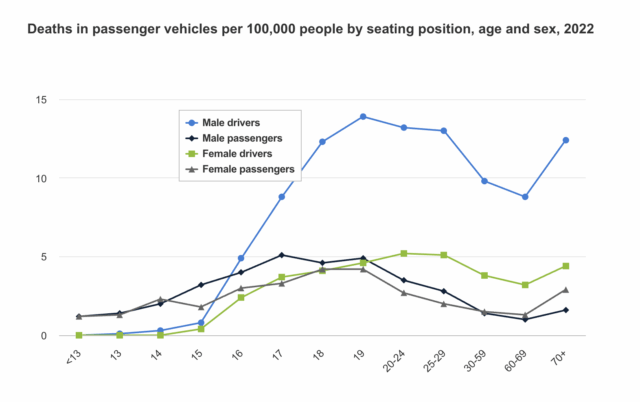

The PFC is essential for most of the aspects of higher-order functioning and the inhibition of impulses. This makes its underdevelopment a key player in the heightened frequency of freak accidents amongst adolescents, such as car crashes and drownings. Teenagers between the ages of 16-19 have a fatal crash rate close to three times as high as the rate for drivers ages 20 and above. Data from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) displays a massive increase in deaths in passenger vehicles for male drivers between 16 and 19 years of age.

Data on deaths in passenger vehicles by age and sex by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS).

“In the prefrontal cortex, between those ages of about 13-25, there is a 17% reduction in the volume of gray matter,” explained Dr. Edersheim. “And so you would think, okay, why would less be more?” The answer, she detailed, is that this reduction is needed for the effective linkage between areas of the brain. The brain really only has so much real estate, so this neural pruning increases the efficiency of our computation capability.

The second change is in the white matter, which makes up the “communication superhighways” of the brain, linking information from one place to another. White matter increases in adolescence, speeding up the connections that the reward network has with the executive functioning system.

And the third and final change occurs in the dopaminergic system itself. “Teenagers and emerging adults have the greatest circulation of dopamine and dopamine receptors of the whole lifespan. You’ll have more as a teenager than you’ll have as a grown-up,” she detailed. “Everything will be more salient, and the drives will be for novelty and rewards,” she explained.

The instant gratification we feel when experiencing a dopamine rush therefore feels even stronger in teenagers and young adults. And they aren’t to blame, or to be paternalized, as the law often does to young people. Teenagers and young adults have no say over the amounts of dopamine in their systems or their heightened susceptibility to addiction.

The Social Media Epidemic and the Corporate Response

The excessive usage of social media — precisely what big technology corporations foster, through the knowledge of children’s susceptibility to addiction, and targeted mechanisms to bring in users — is inextricably linked to a variety of negative outcomes, disproportionately so for younger individuals.

Spending more than three hours online correlates with adolescents internalizing their problems, and social media has been studied to latch on to our innate tendency to compare ourselves with others. These comparisons can often lead to decreased self-esteem, particularly in adolescents, who have a heightened level of care for others’ opinions of them. In turn, low self-esteem is correlated with suicidality. One in three teenage girls considered death by suicide in 2021. These phenomena are inextricably linked to the excessive usage of social media; in fact, research shows that reducing our social media usage significantly improves body image, which is a large part of one’s self-esteem.

Meanwhile, corporate actors, well-versed in developmental neuroscience, use this information to systemically target their consumers and shape their profit maximization strategies. In 2018, Meta conveyed a rather dehumanizing statistic in their internal correspondence: the lifetime value (LTV) of a young user was cashed in at $270 in profits for the company. As part of the email, the company noted, “you do not want to spend more than the LTV of the user,” warning corporate employees to be mindful of their cost-benefit analysis.

In one of the few public rebukes, CEOs from Meta, TikTok, X, Discord, and Snapchat were grilled in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee in January of 2024. The CEOs, unmoved by multiple Senators describing the overabundance of suffering caused by their platforms, went on to rattle out meaningless statistics expounding the safety of their respective corporations.

In 2018, Meta conveyed a rather dehumanizing statistic in their internal correspondence: the lifetime value (LTV) of a young user was cashed in at $270 in profits for the company

In this hearing, Zuckerberg faced many families whose children faced pain, some of whom passed away, at the hands of Facebook. He publicly apologized to these individuals, but also repeatedly rejected any link between mental health and social media usage, ignoring the wide swath of existing research linking the two. At one point, he stated, “it’s important to look at the science, and the bulk does not support that.”