Surveillance Advertising

How you are tracked, commodified, and sold, and what to do about it

Amer Mneimneh

April 4, 2023

This is a story about you. It is a story of how you are followed throughout your day, how you are bought, taken apart, sold, rebuilt, and sold again to the highest bidder- giving anyone, be it an advertiser, law enforcement, or political actor access to your recorded digital existence.

Surveillance advertising, known as ‘behavioral advertising’ by its supporters, is the systematic harvesting, marketing, and utility of digital surveillance through mechanisms such as cookies, advertising identities, and browser fingerprinting. The two most ubiquitous methods of identifying unique users are cookies and advertising trackers. A cookie is a small text file stored in your browser when you visit a website. It can perform helpful tasks such as reminding the site that you’ve already logged in, or that you left items in your shopping cart. However, because cookies almost always rely on a unique identifier to provide these services, they can also be used to track you. Furthermore, a website may choose to host third-party cookies, which don’t serve any direct purpose to their host site, but instead report back to another computer information about the user. For example, the Facebook Pixel is a 1×1 transparent pixel, or bit of your screen, that can be hosted on a webpage. When a user connects to the site, by default, their browser will request to load the Pixel, which installs a cookie on the user’s browser and informs Facebook of the user’s session not just on its own site, but across the internet at large.

Taken across the entirety of a user’s online experience, and combined with other data-harvest schemes such as search engines, e-mail services, and social media, these systems allow Big Data advertisers to determine a highly accurate, and surprising, picture of the subject’s life. One company, Acxiom, claims it can sort its advertising data by the following variables: household size, age, full date of birth, occupation, newspaper readership, probability to use the internet for gambling, probability to read news online, and age of youngest child. Another, Epsilon, sells access to consumers anchored in a “complete name and address validated by transactions,” promising minutiae such as hobbies, age, stage of life and income in their advertising materials.

Taken and Sold, but not Controlled

The default acquisition of this data is to take first then ask for forgiveness later. If like 120 million other Americans, you use Verizon Wireless, you are automatically enrolled into a program which collects your location and telecommunications data. Using an Apple or Android phone assigns a unique identifier to your device that must be disabled manually. According to Elea Feit, senior fellow at Wharton Customer Analytics and a Drexel marketing professor, “Most companies are collecting data these days on all the interactions, on all the places that they touch customers in the normal course of doing business … every time you interact with the company, you should expect that the company is recording that information and connecting it to you.” But that data doesn’t merely sit in the host’s data bases–though you may be satisfied by Facebook’s animated guide to privacy which characterizes this relationship as ‘Working Together’, and feel trusting of Facebook itself, your data may end up far beyond the social media network. Data is now a commodity, and can be sold and utilized by a third party without your consent. For example, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) reportedly purchased location data derived from mobile ads in support of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations. The Republican Party leaned on Cambridge Analytica, a British private intelligence firm using Facebook-derived marketing data, in targeting voters in swing states in the 2016 election. As early as 2013, Pam Dixon from the world Privacy Forum testified to congress about commercially available databases of rape victims, genetic disease sufferers, and people suffering from addictions, for as cheap as 7.9 cents a name.

Data can also be stolen by a third party as 533 million Facebook users discovered in 2019. Alternatively, partitions between data can become compromised, as when a hacker in 2020 made all DNA data on GEDmatch available to law enforcement, to include users who chose to opt-out of law enforcement access. When data is treated like a commodity, your data is only as secure as the weakest link in the commercial chain. You are always one disgruntled employee, unpatched server, or phishing email away from digital compromise. With so much of our individual privacy at risk with this system in place, it begs the question: why do we have it?

How Did We Get Here?

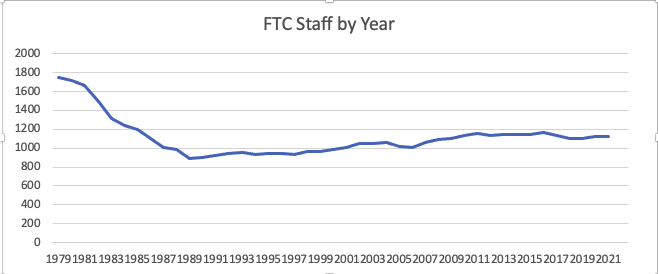

According to Calli Schoeder, Global Privacy Counsel at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, surveillance advertising has its roots in the ability of technology to outpace legislation. “There’s a real disconnect between the speed with which technology develops and the speed with which laws adapt to address that technology. Laws just can’t keep up in a lot of cases.” Whereas the European Union has the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a 2016 law that granted significant rights to data subjects and regulatory responsibilities on data processors, there is no single primary data protection legislation in the United States. Rather, there are hundreds of laws at both state and federal level, ranging from the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) charter to bring enforcement actions against unfair or deceptive practices, to California’s Consumer Privacy Act which empowers consumers to know when their data and to delete or opt-out of it, to Massachusetts’ data protection regulations which impose standards and penalties for poor data protection. When data matters are brought to congressional attention, it has often been the case that the data processors themselves explain what their products do, instead of a third party.

“There’s a real disconnect between the speed with which technology develops and the speed with which laws adapt to address that technology. Laws just can’t keep up in a lot of cases.”

As Schroder says, data giants emphasize “one of those false dichotomies” presented to legislators, which couches these issues as privacy being the price the industry pays for innovation. What social benefit this innovation provides, besides billions in dollars to a select few, is both unclear and counterbalanced by the outsized role surveillance advertising has played in polarizing the nation and reinforcing social inequities.

Political Polarization

Have you ever opened a social media application, then closed it, then within moments opened it again? Have you lost long spans of time to endlessly scrolling your feed? Don’t feel bad- you’re the subject of a concentrated effort to grab onto and retain your attention. Your experience on a social media platform is designed to maximize your engagement with the service- the more time spent sharing, reading, or responding to posts and messages, the more data is generated, and the more time spent looking at advertisements. However, this addictiveness has a serious social drawback in the content it tends to prioritize. As one paper describes, content that is popular within your own ‘in-group’ on social media rises to the top of your feed, usually that which confirms your pre-existing beliefs, or which inspires fear and outrage. Rather than being exposed to moderate views outside your own, you are are shown the worst of ‘out-groups.’ Again- this is not an intentional aspect of the algorithm, but a byproduct of its viewership-optimization attempts. In an experiment, researchers at Facebook generated a test account: a politically conservative mother from North Carolina, who liked Fox News and Donald Trump. Within two days, “Carol” was being offered QAnon groups. Within a week, Carol’s feed was “full of groups and pages that had violated Facebook’s own rules, including those against hate speech and disinformation.”

Another study in 2021 found that Facebook’s algorithm limited audience exposure to novel or counter-attitudinal perspectives.

There is notionally a debate about whether social media, particularly Facebook, facilitates polarization and animosity. A wide range of experts from various institutions have highlighted the correlation between political polarization and the use of social media, and their opposition consists of Facebook insisting they, in fact, are not responsible.

Microtargeting and Society

Aside from their tendency to show the worst in others, social media platforms are enabled by surveillance advertising to serve you, specifically, you, misinformation from the highest bidder. The same mechanism that allows a budget hunting apparel manufacturer to target working class rural Americans interested in the 2nd Amendment allows politicians and foreign state actors to do the same.

Black Americans were targeted with voter apathy messaging, encouraging them to abstain from this election cycle.

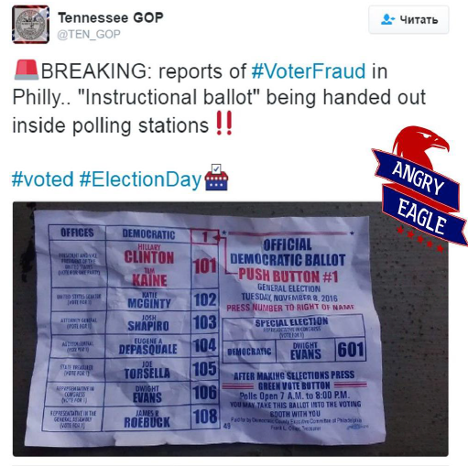

During the 2016 election, the Russian government-affiliated Internet Research Agency (IRA) targeted Americans along social fault lines for misinformation and political advertising with specific agitation goals in mind. For example, the IRA filtered their “Support Law Enforcement” Facebook pages, which featured some of the earliest attempts at a voter fraud narrative, to men starting at age 45. Some ads were far more specific, such as the “Stop All Invaders” IRA-run site, which targeted Alabama, Georgia, New Mexico, Arizona, and Texan users interested in the 2nd Amendment, the NRA, stopping illegal immigration, or Donald Trump for President. Black Americans were targeted with voter apathy messaging, encouraging them to abstain from this election cycle. The seeds of voter fraud allegations were also planted during this time, targeting GOP and right-leaning voters.

Examples of voter apathy memes used by the Internet Research Agency in the 2016 election.

Voter Fraud messaging used by the IRA in the 2016 election. Note the language in the top right corner. Credit: University of Lincoln – Nebraska.

Surveillance advertising has also been accused of manipulating elections outside of America. Trinidad and Tobago’s electorate largely votes along ethnic lines, split between Afro and Indo-Trinidadians. In 2010, Cambridge Analytica sent messaging targeting Afro-Trinidadians, discouraging them from voting in the upcoming Parliamentary elections. The Indo Trinidadian party won the 2010 election. In a brochure by Cambridge Analytica’s parent company, Strategic Communication Laboratories Group Elections, it also claimed to have used ethnic tensions to interfere with the elections of Latvia in 2006, and Nigeria in 2007. Although Cambridge Analytica has since been shut down, its founders have moved on to form new consultancy firms.

Digital Redlining

Because microtargeting allows advertisers to discriminate on which demographics they advertise to, it also allows these advertisers to reinforce social inequities and transfer their own prejudices. If you are Black, advertisers may choose to target, or not target you based on your race. Even without targeting your race, advertisers can ride on the social inequites formed during redlining to effectively target your race by targeting your zip code. ‘Redlining’ was the practice of denying loans to potential customers based on their zip code, almost always coded to target low-income households, racial, and ethnic minorities, independent of their ability to pay.

Digital redlining, or, as the ACLU specifies, algorithmic redlining, is the use of digital technologies to entrench discriminatory practices against already marginalized groups. In one current case, Opiotennione v. Bozzuto Management Company, et al., the plaintiff, a 55-year-old, alleged he and other older people were excluded from receiving housing advertisements based on their age. A related concept, reverse redlining, is when inferior services are intentionally targeted minority populations. One case, Vargas v. Facebook, currently in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, a Latina plaintiff was shown different housing opportunities on the defendant’s website for the same search as her Caucasian friend. A recent case in Florida, Britt v. IEC Corporation, featured a Black man who was targeted on Facebook by Florida Career College, a for-profit vocational school. In an ad which emphasized Mr.Britt’s poverty, asking “Are you tired of working minimum wage jobs?” and featured Black models, Mr.Britt was offered instruction as an HVAC technician. However, after taking on immense debt to pay for the education, he found the education he received to be subpar, and was unable to find employment after his course. According to data from 2018 and 2019, FCC in Tampa had a rate of 85% Black or Latino enrollments, a graduation rate of 44%, and a net cost of $33,049. According to the Predatory Student Lending project at Harvard Law School, FCC Hialeah had a 55% Black student enrollment in a city with a 2.5% Black population. The FCC case remains in arbitration, while its former students remain liable for their student loans.

Undermining Public Health

Microtargeted ads were also used to spread misinformation during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. While you were stuck inside your home, awaiting the news of a vaccine or end to the pandemic, you may have grown more reliant on social media and news websites for information. If you were targeted by malign actors, you may have seen messaging claiming the virus was non-existent, or calls to defy lockdown orders. In March 2020, COVID misinformation started to overwhelm fact-checking organizations, as the pace of misinformation exceeded the ability of human moderators to remove it. Even when posts were flagged as false, they would often remain on the social media platform with no further action- for example, 59% of posts flagged by fact-checkers on Twitter remained without any warning labels. One study noted the rapid growth of the World Doctors Alliance, an anti-vaccine group which rose sharply in popularity in 2020. Another experiment intentionally submitted misinformation ads to Facebook, which were approved for use until Consumer Reports messaged Facebook administration. These ads included claims like ‘Coronavirus is a HOAX’, and ‘Social distancing doesn’t make any difference AT ALL, it won’t slow the pandemic, so get back out there while you still can!”

Content moderation is handled by the social media platform. These processes are often opaque and self-regulated within the organization. Advertising on social media platforms is meant to produce as much money as possible for the platform, so much of the content filtering relies on automatic detection of key words (‘COVID,’ ‘Democrats’) and advertisers self-reporting if their content is political. If an ad can escape these two filters, it can reach its targeted demographic with ease.

But the algorithms are not enough. Facebook offered to advertisers people interested in the topics “Jew Hater,” “How to burn Jews”, and “History of why jews ruin the world.” The ‘pseudoscience’ advertising demographic on Facebook was linked to ads which claimed 5G towers were responsible for the Coronavirus.

Both advertising groups emerged algorithmically- meaning that the social media platforms automatically generated them in observation of how content was used on the platform. Both groups were also only eliminated when the media brought them to Facebook’s attention. This presents the critical weakness in content moderation on social media platforms: the current system is akin to a game of Whack-A-Mole, with a handful of players and hundreds of millions of moles. In such a poorly regulated system, microtargeting allows the most malign actors with a modest budget almost unfettered access to their target populations.