But while Dolovich hypothesized that this psychological distress would “tend to subside the farther away from [Harvard Law School] people get,” that does not seem to be the case. While at least one study has suggested lawyers may not be any more unhappy than anyone else—perhaps more of a condemnation of our society rather than an acquittal of the legal profession—researchers and industry stakeholders have repeatedly sounded the alarm, suggesting that American legal profession is facing a well-being crisis.

For example, in Massachusetts, a 2023 study commissioned by the state’s Board of Bar Overseers found that among the Massacchusetts lawyers surveyed, 77% reported work-related burnout, along with anxiety (26%), depression (21%), suicidal ideation (7%), and unhealthy alcohol use (42%).

“We also identified an alarming gap between lawyers who reported anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and hazardous or unhealthy alcohol use and those who sought care,” the researchers wrote in their report. “The largest perceived barriers preventing lawyers from seeking care include concerns about stigma, including loss of dignity, embarrassment, injury to pride, not acknowledging their own need for care, or family, friends, or colleagues finding out.”

At the same time, emerging trends in organizational studies seem to suggest corporate professionals more broadly are increasingly experiencing the impacts of a psychological phenomenon known as “moral injury.” Which leads us to two questions: when it comes to lawyers’ mental health and wellbeing challenges, is moral injury playing a role? And, if so, is that something law students should factor into their career decision making?

Moral injury refers to “the lasting strong cognitive and emotional response that is caused by performing, witnessing, or failing to prevent an action that violates one’s own moral beliefs and expectations.”

Although the term can be traced back to at least the 1990s—often attributed to Department of Veterans Affairs psychiatrist Dr. Jonathan Shay—it remains a developing concept; one of which “acceptance … has outpaced scientific knowledge.” In comments to the Military Times in 2023, Brett Litz, Professor of Psychiatry and Psychology at Boston University School of Medicine and a leading expert of moral injury, suggested that this could be down to moral injury’s intuitive appeal, as people “understand from personal experience that [morally injurious events] can have lasting existential impact.”

In 2022, an international group of moral injury researchers—among them Professor Litz—undertook the task of defining moral injury, ultimately producing the first standardized assessment, the “Moral Injury Outcome Scale.”

In investigating the parameters of moral injury, Litz et. al. identified associations between experiencing a “potentially morally-injurious event” (PMIE) and certain symptoms typically linked to PTSD and depression—such as re-experiencing the event(s) in question through flashbacks or nightmares, avoidance in terms of thinking about the event(s), hopelessness and loss of joy or pleasure.

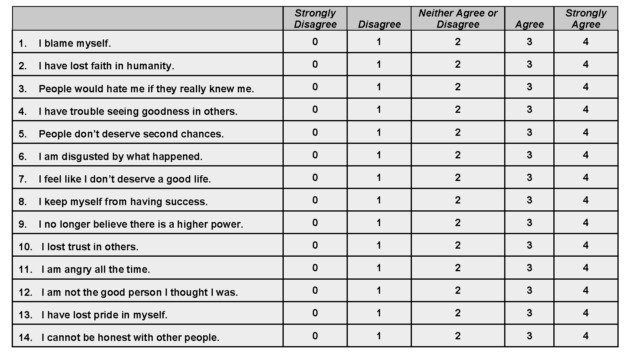

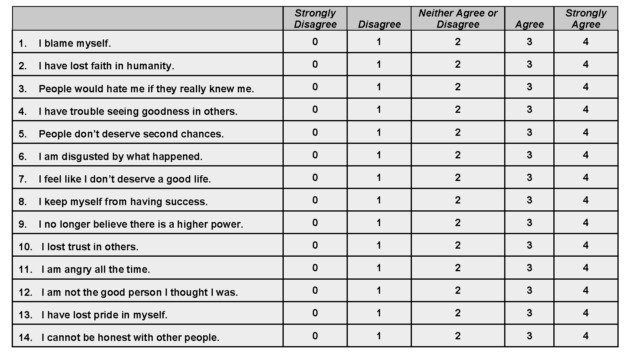

The Moral Injury Outcome Scale itself, meanwhile, asks patients to scale their response to various statements related to feelings of shame or violation of trust, including: “I have lost faith in humanity,” “I am not the good person I thought I was,” or “I am angry all the time.”

Source: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

At the same time, though, some scholars, writing in the context of climate-related distress, have argued moral injury is not necessarily itself a pathology—but rather a “painful reality” that “represents the best of humanity, our ability for kindness and care, and is therefore something we should strive for.”

Historically, much of the academic research into moral injury has documented its prevalence among military members and veterans. Moral injury has recently received increasing attention among frontline health care workers in Europe and the United States, in relation to, for example, the Covid-19 pandemic.

“We need to start with honesty, and with clarity that what many are now calling ‘burnout’ is actually moral injury.”

However, there has also been increasing interest in the psychological and spiritual harm that can arise from experiencing potentially morally injurious events in corporate settings—which, in the U.S. context would, of course, actually implicate health care workers.

Indeed, shortly before the Covid-19 pandemic arrived in Europe and the United States in January 2020, Dr. Wendy Dean, a former practicing physician and co-founder of the non-profit The Moral Injury of Healthcare, wrote for WBUR: “We need to start with honesty, and with clarity that what many are now calling ‘burnout’ is actually moral injury.”

More recently, in the 2023 book If I betray these words: Moral injury in medicine and why it’s so hard for clinicians to put patients first, Dr. Dean and her co-author, surgeon and Harvard Medical School Professor Dr. Simon G. Talbot, tracked how economist Milton Friedman’s doctrine of shareholder primacy has in fact created a moral injury epidemic among mission-driven health care workers.

“At the heart of nearly every conversation we have had with clinicians in the last five years is some version of ‘this wasn’t what I signed up for,” a nagging sense that the covenant between physicians and their employers is broken,” they write.

Moreover, even beyond particular corporate-captured fields such as health care—where, arguably, employees are distinctively mission-driven—the Harvard Business Review in 2022 proclaimed that even in more traditional corporate contexts, “employees are sick of being asked to make moral compromises.”

Meanwhile, Robert Prentice, a professor of business law and business ethics at the University of Texas at Austin, speculates: “If much of your career has involved hiding debt for Enron, creating fake customer accounts for Wells Fargo, manipulating LIBOR for Deutsche Bank, creating software cheat devices for Volkswagen, or saddling minorities with sub-prime mortgages for Countrywide Financial, you might well feel moral injury.”

These hypotheses are starting to be borne out in recent academic literature—including in legal contexts. For example, in one recent study from the United Kingdom published in the Journal of Business Ethics in February 2024, British researchers Karina Nielsen, Claire Agate, Joanna Yarker and Rachel Lewis undertook a novel, qualitative examination of moral injury in business settings.

“employees are sick of being asked to make moral compromises.”

“Moral transgressions in business settings may not entail life or death situations as in healthcare and military settings,” the authors explained, “Yet they may significantly impact on those whose moral beliefs are transgressed.”

Through interviews with workers across professions—including law—the authors found that in corporate contexts, potentially morally injurious events might, broadly speaking, fall within two categories.

The first category involved ongoing moral transgressions that threatened the reporting worker’s identity as a “good person who would do the right thing”. The second concerned participants being asked to do something against their moral values—whether as “part of daily business in the organisation” or “related to a specific role or responsibility.”

Reflecting on the latter, the authors quote one lawyer interviewed for the study, whose words might sound familiar to many in the legal profession.“It doesn’t matter what I personally believe about whether this person was racist, or sexist, or what about trans rights,” that lawyer said. “My job is just to defend this claim to the best of my ability and that’s what I’m getting paid for.”

Similarly, in U.S. corporate law, one can imagine how moral injury might arise in the context of being involved in, or adjacent to, the representation of controversial clients. However, say a corporate lawyer spends their days facilitating the corporate processes and formalities necessary to immunize a corporation from veil-piercing—in other words, the shielding of shareholders’ assets from claims against a corporation found liable for wrongdoing. Or perhaps their role frequently involves invoking cases like Graham vs. Allis-Chalmers, In re Caremark or In re Citigroup to protect corporate directors from liability in the face of significant corporate harms.

“My job is just to defend this claim to the best of my ability and that’s what I’m getting paid for.”

Indeed, in those kinds of situations, one can also easily imagine a lawyer who considers themselves to be—as Nielson et al describe—a person who “would do the right thing” experiencing an ongoing, morally injurious transgression arising via participating in, and thus legitimizing, corporate law—a doctrinal system that places shareholders (a euphemism for, as Jessica Graham argues, profits) above all else.

If the hypothesis that lawyers are experiencing moral injury is in fact onto something, the question then becomes: how should lawyers respond? Beyond the notion of law students self-selecting out of corporate law—or certain firms—altogether, climate crisis activism in Europe offers an early example of responses from lawyers already established in the profession.

![[F]law School Episode 8: Selling Harvard Law Students](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Screenshot-2024-09-08-at-9.59.54 AM-640x427.png)