As with so many elements of civil immigration enforcement, electronic monitoring first took root in the criminal legal context, where it was envisioned as a “progressive alternative to imprisonment.”

Michelle Alexander, civil rights lawyer and author of The New Jim Crow, takes issue with this characterization. In in a 2018 op-ed titled “The Newest Jim Crow,” she wrote, “Many reformers rightly point out that an ankle bracelet is preferable to a prison cell. Yet I find it difficult to call this progress. As I see it, digital prisons are to mass incarceration what Jim Crow was to slavery.”

Alexander warned of “a system of ‘e-carceration’ that may prove more dangerous and more difficult to challenge than the one we hope to leave behind.” “E-carceration,” coined by activist and writer Malkia Devich-Cyril, is “the use of technology to deprive people of their liberty.” The term encompasses a whole host of technologies, ranging from license plate readers to risk assessment algorithms, but electronic ankle shackles remain the most familiar example. Through the lens of e-carceration, electronic monitoring is not an alternative to incarceration as much as it is an alternative form of incarceration.

The experiences of immigrants on ankle shackles bear this out. A 2021 study found that the effects of ankle monitoring mirror the effects of detention: physical harm, mental trauma, social isolation, financial hardship, and destabilized families and communities.

Many respondents to the study’s survey grappled with still feeling confined despite their release from physical incarceration. One individual summed it up: “I’m happy for my freedom, but I don’t feel free. I want to be free, free.”

For Zheng, the hardest part was the constant reminder that he might be deported. After being locked up for 21 years, he had looked forward to living as normal a life as possible. But while enrolled in ISAP, he did not feel free to plan for the future. Buying a car or a house seemed pointless when he was wondering if he was about to be “put on a plane.”

“E-carceration . . . is opaque. It represents in my mind a kind of slow violence,” Devich-Cyril reflected during a recent webinar discussion on the future of surveillance and mass incarceration. “It’s framed as humane but, to me, it’s the very mundanity of it—of these tools—that is actually so incredibly brutal.”

“I’m happy for my freedom, but I don’t feel free. I want to be free, free.”

The specter of choice, the abstractness of technology, and the isolation of its subjects all work to hide the harms of e-carceration—as well as those behind the harms. As Holper put it, unlike a detention facility, an ankle monitor is “not something you can stand outside and protest.” On the webinar, Devich-Cyril referred to this as “invisibilization . . . the invisible nature of this kind of coercive power and the danger of that.”

Another core feature of e-carceration, as Devich-Cyril conceptualizes it, is “this way [it] helps states become indebted to corporations and corporate power.”

Public-private partnerships, real and imagined, power e-carceration. In the immigration context, the state-sanctioned partnership is the contractual relationship between ICE and BI. Though Libre now clarifies on its website that it is a “private, for-profit organization,” the experiences of past and present clients reveal that the company has long traded on its mistaken affiliation with ICE.

It’s no wonder why corporations like BI and Libre have found their way to the ankle monitoring of immigrants. The profits are enormous. BI’s new $2.2 billion, five-year contract with ICE averages out to $440 million per year. Under the Trump administration’s draconian immigration policies, Libre’s yearly income doubled to more than $60 million.

The market structure is also ideal. BI, as the sole contractor running ICE’s primary alternative to detention, and Libre, which appears to be the only provider of its kind so far, face no competition in the niches they have carved out for themselves in this market.

As corporations, however, BI and Libre always have their sights trained on even more profit. And there are several ways to get there. To maximize their earnings from electronic monitoring, these corporations still have a stake in the increased detention of immigrants—so that more individuals overall can be considered for alternatives offered by BI or require bonding out by Libre.

Back in 2017, Libre CEO Donovan said he wasn’t concerned that President Trump’s plans to build more detention centers might hurt his business. For private prison companies also in the business of detention, like BI’s parent company GEO, this means that campaign contributions and lobbying expenditures made with an eye toward detention policies continue to serve them well.

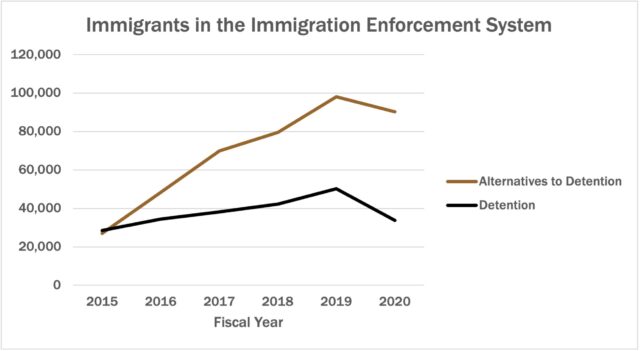

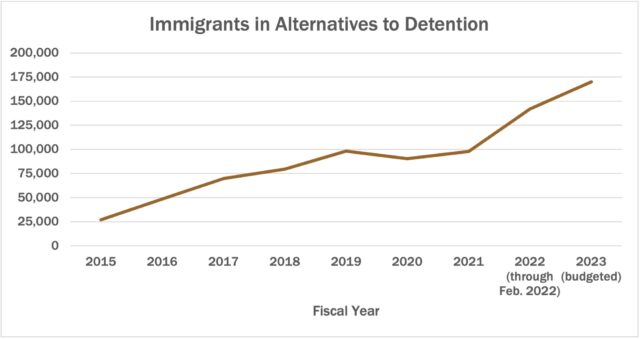

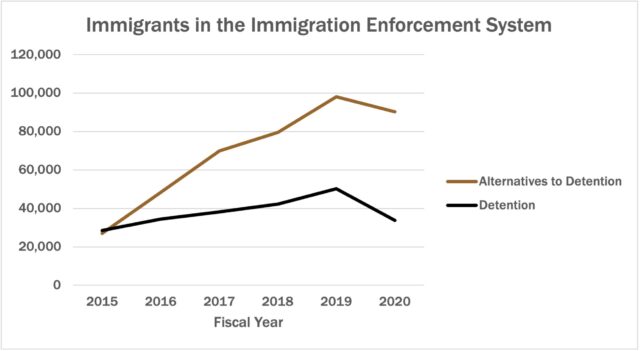

As it turns out, they can have the best of both worlds. Though advocates of alternatives to detention—including the Biden administration—maintain that such alternatives will shrink the population of detained immigrants, a comparison of the available data shows that, at least prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the very opposite had been true.

The average daily population of immigrants in alternative-to-detention programs, compared to the average daily population of immigrants in detention, between fiscal years 2015 and 2020. The decline in both in FY 2020 is largely attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic. Sources: American Immigration Council (citing DHS statistics); ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (FY 2020).

Any fluctuations in the number of immigrants in detention have paled in comparison to the rise in the number of immigrants enrolled in alternatives. Instead of replacing detention, electronic monitoring has offered a way for ICE to track immigrants who would have never been detained in the first place. This expansion of the pool of candidates for so-called “alternatives to detention” has led to rapid growth in the use of electronic monitoring—and the profits available.

During the early years of ISAP, ICE enrolled only immigrants who fell within specific, selected categories:

(1) [those] who are in removal proceedings but have not yet been issued final orders of removal and may be at risk to flee; (2) [those] who have been issued final orders of removal and are considered dangerous, but who cannot legally be held in custody any longer; and (3) [those] with final orders of removal who have been released from custody on general orders of supervision, but who have violated their orders by committing crimes or otherwise failing to comply with release conditions.

And in 2009, the first year of ISAP’s nationwide expansion, ICE issued policy guidelines stating that an immigrant should be released entirely from detention if “[their] identity is sufficiently established, [they] pose[] neither a flight risk nor a danger to the community, and no additional factors weigh against [their] release.”

Now, however, these “low-risk individuals,” including asylum seekers with extensive community ties and mothers released from family detention, are routed into ISAP.

Lobbying could explain this shift. In 2021, BI’s parent company, GEO Group, disclosed $3.6 million in lobbying expenses, focused on “promoting the benefits of public-private partnerships” not only in “the delivery of support services in secure correctional and detention facilities” but also in “electronic and location monitoring services.”

Libre’s founders are themselves former lobbyists on behalf of the bail bond industry. They now hire their own lobbyists. CEO Donovan told The Post that his company is pushing for immigration reform “that would put [Libre] out of business.”

But in a country that has failed time and time again to pass comprehensive immigration reform, his solution centers not policy proposals but business development: “What we’re going to end up with is internment camps along the Southern border, and people wasting away in them. And I know that we are the only hope that a significant number of those people will have. . . . So I’ve got to figure out a way to grow our business to serve more of them.”

Libre and BI’s profits further depend on the length of time an immigrant is being monitored. “They try to keep the ankle monitor on as long as they can,” Zheng said. “They’re not trying to get it off of you.”

There is no formal limit on how long an immigrant can be sentenced to an ankle shackle in the civil immigration system, but the criminal legal system has embraced lengthier and even permanent ankle monitoring. Some Libre clients are shackled for so long that their total fee payments have surpassed the amount of their original bond.

This of course also has to do with the high fees set by Libre, another avenue to increasing profit. The federal government currently pays BI for the costs of electronic monitoring. However, electronic monitoring in the criminal context has seen the rise of “no-cost contracts” for the government, which live up to their name by passing costs onto the people being monitored. This model could become the latest trend imported from criminal enforcement to immigration enforcement, which would allow BI to charge user fees like Libre.

The profiteering by BI and Libre is not all that surprising. After all, it is a corporation’s existential purpose to maximize profits—its value to shareholders. In fact, its directors and officers have legal duties to ensure that they act in the interest of those shareholders.

Corporate law offers no protection to other constituencies, leaving the job to other areas of the law—like government regulations or private contracts. But it is difficult to see how that plays out in the context of immigrant e-carceration, where the government cedes oversight of state functions to corporations and where the contracts present a false choice.

Some immigrants subject to electronic monitoring by Libre have found success with consumer protection laws. A class action by Centro Legal de la Raza and its partners led to a $3.2 million settlement in 2020 that included payments and debt relief to current and former Libre clients.

Libre also agreed to certain changes to its business practices—including no longer using ankle shackles. As part of the settlement, the company committed to transitioning to “wrist bracelet monitor[s] or other similarly less intrusive monitors, such as cellular telephones or periodic check-ins.”

Reflecting on the case, Newmark, Centro’s litigation director, said, “Most meaningful to me, we were able to get a number of policy changes that our clients thought were most important.” Ending Libre’s use of ankle monitoring was one of those priorities for the four plaintiffs who brought the class action on behalf of their fellow Libre clients.

Still, when going up against corporations, class actions and other civil litigation offer a limited tool. Lawsuits are geared toward winning financial compensation for discrete harms rather than wholesale changes in corporate policies and practices, according to Newmark.

“You can look for things that break specific regulations. . . . ‘Don’t do this. You’re clearly violating this. You have to stop that,’” Newmark explained. “But in terms of ‘Hey, we’d like to see less of this, more of this’ or ‘This practice has to be done better,’ when those practices are problematic but not unlawful, it’s difficult to get that done through a class action. The only option is to negotiate to try to get the corporation to agree to those changes, using its liability for any actual legal violations as leverage.”

Like virtually all settlement agreements, the one between Centro’s plaintiffs and Libre also clarifies that it does not represent “an admission or concession by [the] Defendant of the validity of any claims or of any liability or wrongdoing or of any violation of law.”

![[F]law School Episode 13: The Migrant Trap](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Drury_FB2-e1742192209662-640x427.png)