“Major corporations in Boston and major institutions like Harvard need to take responsibility for the housing crisis that they in part create.”

-Kevin Carragee

According to the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation (ABCDC), average rents for family sized units (3 bedrooms) increased by 30% between 2017 and 2019, while rents for all units increased by 32%. In order to afford a three-bedroom, a family in Allston/Brighton would need to pay 63% of the median income, approximately $52,000. An individual working full time at minimum wage would have to allocate 100% of their earnings to rent. The poverty rate in Allston-Brighton is 29%. The increase in rents contributes to an increase in homeownership cost and Allston has some of the lowest homeownership rates in Boston, at just 10%.

While the rising costs are driven by many factors, Harvard’s expansion into Allston is a significant contributor, and will ultimately exacerbate the problem. 80% of Allston/Brighton residents are renters and as of 2019, 12.4% of private housing was occupied by students. In 2019, a student in a three-bedroom apartment paid an average of $930 per bedroom. In order for a family to afford the same unit, they would have to pay $2,800 and make $110,000 per year to maintain the HUD-recommended 30% rent-to-income ratio.

Meanwhile, investors looking to buy property calculate the amount they are willing to pay based on the projected rental amount. As rents increase, the cost to buy increases, and the cycle continues. While the majority of the current student renters are those from Boston College and Boston University, the new Harvard Enterprise Research Campus is sure to draw thousands more graduate students and young professionals who will seek nearby housing. The rental vacancy rate in Allston/Brighton is only 5% and the existing housing stock cannot accommodate the rising demand. New construction has primarily consisted of market rate studios and 1-2 bedroom apartments and condos, which though suitable to the incoming Harvard scientists, are not appropriate for families.

The correlation between decreasing affordability and increased student populations is not unique to Harvard. A recent report commissioned by The American City Coalition, showed that the number of Northeastern students living off-campus in Roxbury increased by 180% between 2015 and 2020, while rents in that neighborhood, historically affordable, have begun to rise.

Harvard’s practice of land banking—acquiring and sitting on properties for years—also contributes to the crisis. Unlike most real estate investors, which evaluate housing on a 10-30-year time horizon, Harvard purchases and holds land for centuries. According to the ABCDC report, “unless Harvard decides to develop housing itself, or to partner with a community group to create new housing, it is extremely unlikely they could ever contribute to alleviating the housing affordability crisis in Allston/Brighton.” When development on the 170 acres of available land begins, the corporate landlords that dominate the Seaport and Kendall Square are guaranteed to swoop in. Carragee explained, “Because of Harvard’s presence, and the knowledge of this massive expansion that will happen over time, the neighborhood’s become deeply attractive area for corporate investment in real estate.”

How does Harvard Get Away with This?

“Developed for whom? Developed in whose interests? Right now it’s all about Tishman. It’s all about Harvard. It’s very little about the people of Allston/Brighton and people of Boston.”

-Kevin Carragee

Over the past thirty years, Harvard has straddled a line between nonprofit university and corporate developer, employing countless tactics with one goal in mind: to maximize profit. Though the relationship between Harvard and the Allston/Brighton community is still tenuous, the relationship between the City of Boston and Harvard has come a long way since the secret holdings were revealed. While the investment in affordable housing and community partnership helped to thaw the tension, there is likely more to the story.

In 1997, the undeveloped land in Allston generated approximately $1.5 million in taxes, as it was held by Beal Companies, a corporate entity. However, the moment Harvard began development, the land became tax exempt, as the property of a non-profit. When the recession hit in 2008, legislative efforts sought to hold universities like Harvard accountable by pursuing a plan that would impose a 2.5% tax on any endowment profit exceeding $1 billion.

Between 1990 and 2008, the Harvard endowment grew from $4.7 billion to $37 billion, and the university paid zero taxes on this growth. As one New York Magazine journalist wrote, “Harvard is a real-estate and hedge-fund concern that happens to have a college attached…the school does not distribute its operating profits as dividends. It has no shareholders. It does not exist to make anyone rich. Yet nevertheless, it is rich, as are a several other universities in its cohort.”

The proposed tax plan would have cost the school $840 million per year. It was met with mixed reviews by the Harvard community. A contingent of students across the university recognized the impact of tax exemption of Harvard’s endowment on its expansion into Allston, explaining in the Crimson:

“Partly due to these reduced expenses, Harvard currently owns over 923,000 square feet of property in Allston that are neither developed for Harvard’s purposes nor leased to Allston businesses. Harvard would be less likely to hold these land lots for long-term construction projects if it had to pay real-estate taxes on them.”

However, others argued that alumni would be less inclined to donate to an institution that was underwriting state or city efforts through tax payments. Famed Harvard economist, Gregory Mankiw posted in his personal blog a scathing response, calling the 2.5% tax “one of the most pernicious ideas [he] had heard of late.” He went on to propose that if the tax should pass, “instead of expanding the university into Allston, Harvard could create a second campus in another state.” Fortunately for Professor Mankiw, the tax initiative ultimately failed.

Having skirted the legislative proposal, Harvard now makes direct payments to Cambridge and Boston in lieu of paying property tax. Two years after the initial 1997 backlash, Harvard agreed to boost its payments to Boston, offering $40 million over 20 years, a $12 million increase over its previous agreement. Though non-profit hospitals, universities, and cultural institutions have made these sorts of payments for decades, in 2012, Mayor Menino formalized these dealings through the Payment in Lieu of Tax (PILOT) program. The new program established a request amount from the city for services received. 50% of this payment could be allocated through in-kind community benefits.

This arrangement saved Harvard over $273 million (0.7% of its endowment) during that period, and reduced its liability to city by over 95%.

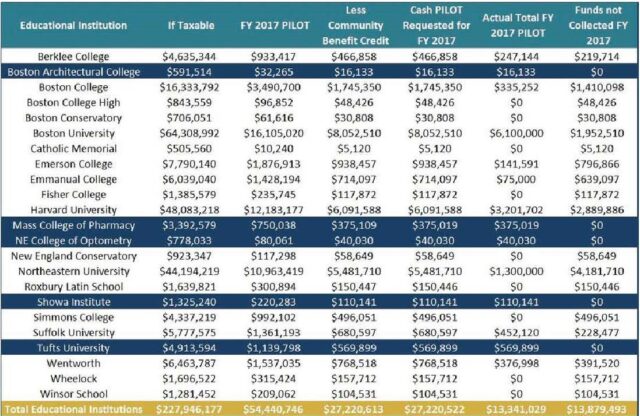

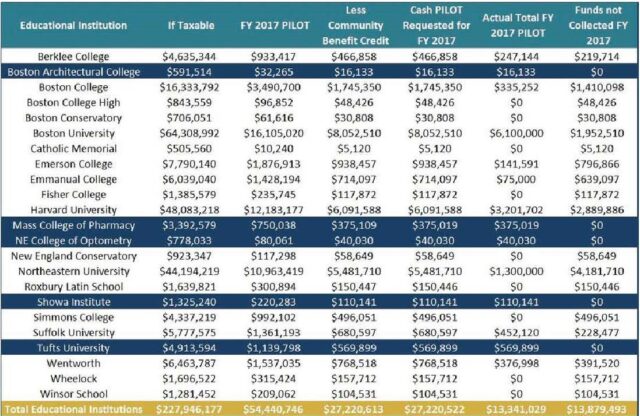

Between 2012-2017, Boston requested approximately $27,800,000 from Harvard. Harvard paid only $15,184,000. If taxable, the land that Harvard owns in Allston would have generated $48,083,218 for the city of Boston in 2017 alone. This arrangement saved Harvard over $273 million (0.7% of its endowment) during that period, and reduced its liability to city by over 95%.

Table of the PILOT payments made by universities in 2017. The schools highlighted in navy blue made full payments that year. Reprinted from “Boston’s Pilot Program, a Fair Deal for Boston Residents.”

The current structure of the PILOT program has been critiqued for allowing up to 50% of the PILOT request to be allocated to “in-kind community benefit.” For universities, there is no regulatory framework or accountability for these in-kind benefits. In the face of pressure from groups like CJAB, Harvard now releases press statements applauding its own generosity. In a letter published by Executive Vice President Katie Lapp this past February, Harvard proclaimed that it would donate a 0.9-acre parcel to an affordable housing developer, that it would ensure 20% of its housing units would be income-restricted, and that it would donate $10 million over five years for affordable housing creation.

While these actions were likely construed as qualifying for the in-kind community benefit credit, these commitments fall significantly short of the $6,680,000 cash request that was made in 2021 alone.

Though Harvard does pay property taxes on its revenue generating properties, it has pursued other creative means to minimize payments. When it starts to build on the 170 acres that are ripe for development, Harvard has indicated that it will do so with ground lease agreements. Under a ground lease agreement, a tenant can develop property only during the course of its tenancy, after which the property returns to the owner. When a landlord executes a ground lease, they don’t report any gains and thus don’t pay taxes on a sale. Rent payments on a ground lease are fully deductible for federal income taxes. They also prevent generational home ownership, as families are permitted only to lease properties, and not allowed to buy them.

Where a corporate entity would be held accountable for its tax payment, Harvard’s ability to negotiate its own contribution undoubtedly creates a conflict of interest when a city like Boston, which relies on these contributions for discretionary use, seeks to hold an institution accountable for it role in community displacement or housing affordability. Now owning one-third of the land in Allston, Harvard is able to leverage its power in Boston as it paves the way for further expansion and cements its role as one of Greater Boston’s largest corporate landlords.

![scales - Logo for The [F]law](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/flaw_scale_divider.png)

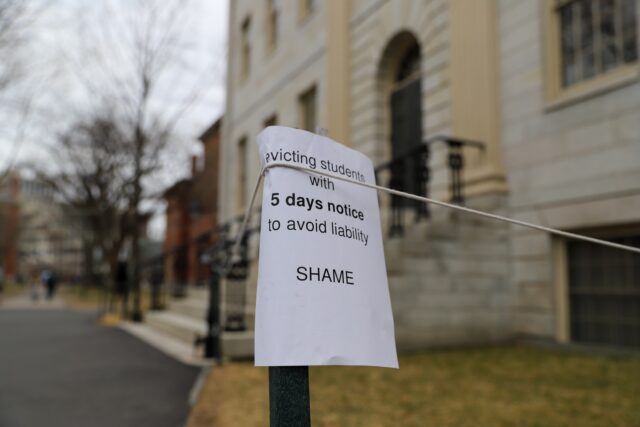

Over the past 30 years, Harvard has grown as a landowner and landlord. With this growth, it has contributed to rising rents and housing insecurity even for its own students. Neighboring communities, governments, and its students have struggled to hold Harvard accountable for the harms it causes as the university contorts itself to avoid legal liability. For years, Harvard has been allowed to leverage its nonprofit status to avoid tax liability, enabling it to buy up land in Allston/Brighton. Harvard has driven up rents indiscriminately, attracting a population to this neighborhood that will surely displace those who have lived there for generations. Meanwhile, it holds sufficient financial and cultural leverage that it can play an outsized role in crafting the rules it will abide by, and unilaterally determines the terms of its interactions with the city of Boston.

Neighboring communities, governments, and its students have struggled to hold Harvard accountable to the harms it causes as the university contorts itself to avoid legal liability.

Corporate law is designed to protect shareholders above anyone else. The tax and transfer system is meant to ensure that more than just those shareholders benefit from corporate profit structures. Housing law aims to equalize power between landlords and tenants. Harvard, one of the wealthiest and most powerful institutions in the country, sits at the intersection of all three areas of law, and yet is immune to each of them.

![[F]law School Episode 8: Selling Harvard Law Students](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Screenshot-2024-09-08-at-9.59.54 AM-640x427.png)