Although the tangible economic impacts of a professional sports franchise is a bad bet in most cases, what’s less debated, even among economists, is the intangible impact of having a team to cheer for. Councilmember Ramachandran emphasizes the broader social value that sports can bring to a city. “Sports teams are important for building morale in the community and having pride for your hometown teams,” she remarks. As Deubert puts it, people generally want where they’re from to be known as a “marquee city.” Prioritizing non-fiscal measures isn’t unique to sports either, clarifies economist Christopher Udry. It’s “true for museums and concert halls as well.” For local leaders thinking about attracting or retaining a professional sports team, the political calculus therefore involves not only the direct financial implications but also a deeply felt sense of civic pride.

“Sports teams are important for building morale in the community and having pride for your hometown teams.”

This emotional investment can lead to decisions where the public assumes a disproportionate share of the costs. The Raiders’ return to Oakland in 1995, after spending 13 years in Los Angeles, provides a cautionary tale against being too eager to provide public funding to team owners. The city of Oakland offered Raiders owner Al Davis $85 million to renovate the Oakland Coliseum, expanding the seating from 54,000 to 65,000, providing new locker rooms, and adding 121 luxury boxes. To raise the money, the city issued bonds that would be repaid by selling personal seat licenses—a one-time fee that grants the holder the right to buy season tickets for a certain seat in the stadium. The money that the local government viewed as an investment in the community was ultimately never recouped, leaving Oakland with significant debt that it’s still trying to recover from.

To be sure, there are broader socioeconomic factors that play into the debt incurred from the Coliseum’s investment. “East Oakland is a historically Black, now predominantly Black and Latino community, and there was purposeful disinvestment into the economic activity around the Coliseum,” explains Ramachandran. “That disinvestment has led that area to be one of the least desirable places to set up a business in Oakland, unfortunately.” The economic pressures facing areas like East Oakland are often magnified by the influence that sports teams wield, using the promise of revitalization to negotiate favorable terms for ownership. Yet, Oakland is just one illustration of a pervasive industry pattern where sports teams leverage their influence over cities.

The Leverage: Structural Inequalities Working Against the Public

The Sherman Antitrust Act is intended to protect consumers against monopolies, one reason being to prevent the abuse of market power. By controlling the number of teams that can participate and setting prices without any direct competition, North America’s four major sports leagues (the NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL) essentially enjoy monopoly power. For most businesses, this would bring them under the scrutiny of the Sherman Act. But not sports leagues.

Professional sports are shielded from antitrust law through a provision called the Non-Statutory Labor Exemption. The principle comes from labor law, and it exempts collectively bargained agreements, which all major sports leagues have, from antitrust scrutiny—even when the agreements might contain provisions that otherwise violate antitrust laws. The exemption is grounded in the idea that the benefits of collective bargaining outweigh the potential negatives of reduced competition typically associated with antitrust violations. These agreements have rules like revenue sharing agreements, salary caps, and luxury taxes that are anticompetitive. Without these anticompetitive rules, smaller market teams would have to compete directly against bigger markets as separate entities and probably wouldn’t be able to survive. Who’s going to watch a team that has no realistic chance at winning?

Source: AI-Generated Image

Under collective bargaining agreements, bigger market teams still maintain an advantage, but it levels the playing field just enough that smaller market teams can remain competitive. These agreements also cover the league’s ability to make decisions regarding the locations of its teams and stadium financing in order to promote its competitive balance and commercial success. As a result, owners enjoy financial stability, and fans benefit from a more competitive product.

“They know the city wants them. ‘Ok, so let me extract what I can from the city.’ As you expand out . . . you’re negotiating against the public.”

However, this has had unintended consequences for the public. As Zimbalist explains, despite the fact that many cities are increasingly capable of supporting a professional sports team, sports leagues artificially restrict the number of franchises in their leagues, allowing them to charge cities higher prices and to bid them against each other. These restrictions present an opportunity for team owners to capitalize on the city’s desire to host a team. As Deubert illustrates, “In a very small micro sense, [owners are] negotiating wisely. They’re asserting their leverage. They know the city wants them. ‘Ok, so let me extract what I can from the city.’ As you expand out . . . you’re negotiating against the public.”

The move is a rational one from the perspective of the owners. Why pay full price for an investment when you can get someone else to foot part of the bill, particularly when it’s how you’ve always done business? Deubert elaborates:

“These owners, who are billionaires, while they may not have a billion dollars of cash on hand, they certainly have the ability to fund these stadiums on their own. They can easily put a hundred million bucks up and get a billion dollar loan, or two billion dollars, from Goldman Sachs or a consortium of banks. But they don’t want to do that, and they didn’t get rich by using their own money all the time.”

While it might be easy to write off all team owners as purely bad actors, and to be fair, some of them are, Deubert reminds us that owners are human beings grappling with a tension between self-interest, which has served them well their whole lives, and wanting to do good. “Some of them are good people. Some…invest a lot in the city and [have] done good work.” But, Deubert adds, “why would I be here when someone across the river is like ‘hey come on over here, we’ll give you 400 million bucks. We’d love to have you.’”

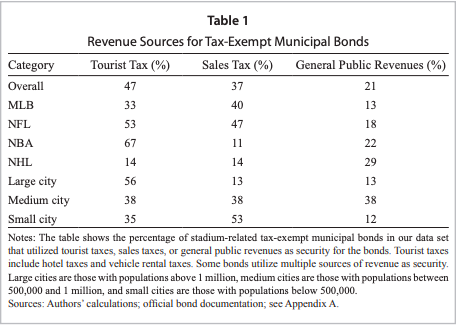

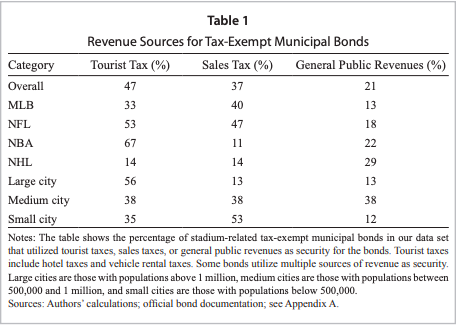

In addition to antitrust law, federal tax law provides another perverse incentive for communities to justify subsidizing stadiums through tax-exempt municipal bonds. Essentially, state and local governments can issue bonds to the public to raise money for public projects, such as building a stadium. The interest on the bonds is exempt from federal taxation, incentivizing investors to, well, invest in the bonds and local governments to issue them. Investors, whether it be regular people or institutions willing to lend the money, get a comfortable, tax-free return on their investment, and owners get the public to pay for part of their new stadiums.

Yet, for locals like Oakland’s Jorge Leon, every dollar divested from the community matters, “as a teacher or a local community leader, you look and say ‘we need those funds,” he says.

This acts as a federal subsidy for the construction of stadiums, meaning that money that should have gone to additional resources for schools, affordable housing, or renewable energy projects is instead transferred directly to the pockets of team owners. The upshot is that every time a team owner uses the proceeds from tax-exempt bonds to build a new stadium or renovate an existing one, taxpayers throughout the country are paying for it in some way.

Admittedly, the size of the revenue loss is a fairly small number when compared to the size of the federal budget—roughly $4.3 billion lost from 2000-2020. Yet, for locals like Oakland’s Jorge Leon, every dollar divested from the community matters, “as a teacher or a local community leader, you look and say ‘we need those funds’,” he says. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 specifically excluded sports stadiums from the list of private activities exempt from taxation for this very reason.

As Zimbalist points out, however, “There are lots of loopholes in stadium financing laws that basically do allow a lot of tax exemptions to go on. There have been efforts to curtail that, but they haven’t been terribly successful.” The loophole that Zimbalist is referring to is something called the private business test, which allows stadium bonds to remain exempt from federal taxation if the city can pay back the bonds through money made outside of the stadium. Two of the main ways to do that is through a tourist tax and a sales tax, both of which have been shown to place a greater burden on poorer residents.

Source: TAX-EXEMPT MUNICIPAL BONDS AND THE FINANCING OF PROFESSIONAL SPORTS STADIUMS (2020)

Whether the advantages are conferred through antitrust or tax law, though, the big beneficiary remains the same: wealthy team owners. And when teams are moved elsewhere, it’s the disenfranchised members in the community that are left holding the bag.

Leveling the Playing Field

So, what can be done to ensure that cities aren’t taken advantage of? For one, the loophole in the Tax Reform Act of 1986 needs to be closed. The most direct way of doing this would be to remove state and local government’s ability to issue federally tax-exempt bonds for the purpose of building stadiums.

To be clear, the issue is not that public funding should never be used to build stadiums, according to Zimbalist—it’s that the public never had a choice in funding the project. “Usually the population in the United States is given a choice. Either we put up this billion dollars or the teams leave it. Very often in those circumstances you can get political buy-in and they’ll say ok we’ll put up the money.” Further, as tickets for sporting events become increasingly unaffordable, the people who are disproportionately bearing the burden of the cost are the ones who least get to enjoy what they’re paying for. Accordingly, if the public is to finance a portion of the stadium costs, it should be subjected to a mandatory public referendum with full disclosure, ideally by a third-party, of the long-term costs.

“Usually the population in the United States is given a choice. Either we put up this billion dollars or the teams leave it. Very often in those circumstances you can get political buy-in and they’ll say ok we’ll put up the money.”

Another avenue is for cities to control their own fates through strict contractual agreements. “When a team comes, they ask for money to build a stadium, you enter a long term contract that requires various commitments…It’s about making the team part of the community and making them feel integrated so they won’t want to leave,” explains Deubert. This could involve giving the city an equity stake in the team or requiring the team to contribute to local community projects. Public referendums on financing stadiums and closing the tax loophole should, at least in part, help cities gain the leverage they need to gain these kinds of concessions in negotiations.

There are contractual measures that can be taken to disincentivize bad actors too. A non-relocation provision, for instance, would subject the team to significant financial penalties if they opted to relocate before the end of the agreement’s term, at which time, presumably, the city will have recouped the value of its investment. The city of Buffalo’s non-relocation provision with the Bills is a great example of such a provision being effective.

Ultimately, while it would be ideal if team owners could fully finance their own stadium projects, there will always be an incentive to use public funding as long as some cities are willing to do so. The key going forward will be to ensure that, if the public is going to pay a portion of the bill, the community is informed of the choice and knows what the long-term costs are. After everything it has been through, maybe Oakland can once again be the city “where everything starts.”

![[F]law School Episode 7: Profit Over People](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Housing-Podcast-Episode-hero-image-640x427.webp)