Representation = Taxation

The fight to make the tax code progressive in 2024

Brandon Martinez

July 9, 2024

In late 2019, Bill Gates (whose net worth, more than 131 billion dollars, marks him as Forbes’ 7th richest man globally) sat for a New York Times DealBook interview. Dressed in slacks, a lavender sweater, sans necktie, his demeanor was, likewise, bemused and muted. Too Big to Fail author Andrew Ross Sorkin queried him:

Sorkin: So there is now, on the table — Elizabeth Warren has a true wealth tax on the table, six percent for billionaires. It would cost you, I believe, close to six billion dollars annually if you had to pay it, on top of what you already pay. What do you think of all this?

Gates supported a higher estate tax and a tax to equate labor and capital income, the income one makes from investments and real estate. But a wealth tax, a tax on one’s assets? He equivocated:

Gates: I’m all for super progressive tax systems . . . so I’m impressed that there are some candidates who go beyond my view, and [yet] I do think if you tax too much, you do risk the capital formation, innovation, U.S. as the desirable place to do companies — I do think you risk that.

Supporting a tax hike can play favorably in the news. In 2024, over 250 individuals wrote an open letter to “the global leaders at Davos,” an annual meeting of the highly exclusive World Economic Forum, with a request to be taxed more. Outlets magnified the message uncritically, even glowingly, with rare exception.

Most Americans support raising taxes on billionaires, and a majority feel bothered by the feeling that some corporations do not pay their fair share of taxes.

The reality, though, is that these days, few billionaires support real-world tax proposals. If they do not withhold comment on bills that legislators are discussing, then the companies they own lobby against higher tax rates. Gates’ interview, in fact, followed a decade-long effort from Microsoft to dodge tax liability for $39 billion in profits. In March 2020, Gates held a 1.34% ownership stake in his former company, valued at over $20 billion.

Polling the mega-wealthy has substituted for a debate on how the U.S. tax code could change. And yet, a movement has emerged to tax wealthy Americans and multinational corporations.

Most Americans support raising taxes on billionaires, and a majority feel bothered by the feeling that some corporations do not pay their fair share of taxes.

Will American democracy prioritize the taxation of the wealthy in 2024? Who will be their best advocates? And when did taxation become so popular, anyway?

Did we ever tax wealthy people more than today?

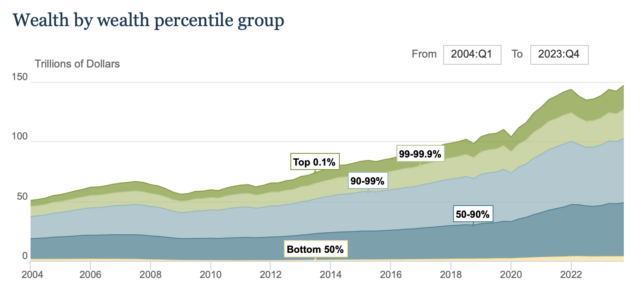

Economic inequality today is unprecedented. As of the end of 2023, the top 10% of U.S. households hold more than double the wealth of the bottom 90%. Meanwhile, in 2022, income at the 90th highest percentile was 12.63 times higher than income at the 10th highest percentile. According to data from the Economic Policy Institute, CEOs in 2022 were paid, on average, 344 times as much as a typical worker.

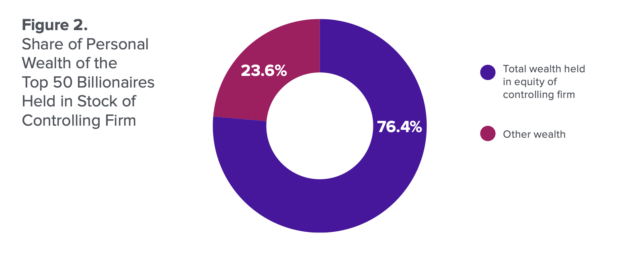

Wealth inequality, 2004-present. Source: Federal Reserve; Source of Consumer Finances and Financial Accounts of the United States.

Economic inequality was similarly stark in the 1920s. In 1928, for example, the top 1% of families received 23.9% of all pretax income. By 1929, the share of income the richest 5% of Americans owned had jumped from 34%, up from 24% a decade earlier.

But over the course of the Great Depression and World War II, tax policy and fiscal interventions in the U.S. changed, redistributing Americans’ income and wealth dramatically. “The corporate tax . . . was proposed originally as a check on the monopolistic power on the dominant firms of the era,” says Emily DiVito, Deputy Director of Financial Regulation at the Roosevelt Institute. The top marginal income tax rate during World War II reached as high as 94%.

In the post-war period, taxes remained high on the wealthiest Americans. A single person in 1955, for example, faced a 91% marginal tax for every dollar they earned over $200,000 ($1.9 million today). Those who died at that time left estates which were taxed at a 77% marginal rate on property worth more than $10 million.

People grew much less wealthy in that time period. Research suggests that the incomes of high earners, including CEOs’ compensation, subsided due to New Deal and post-World War II taxation policy. Reports from the time suggest luxury goods and yachts and vacation homes were much smaller in size, and CEOs rejected pay increases because they expected to retain little post-tax income.

All the while, this was a period associated with an annual economic growth of 3.9%, more than double the 1.8% growth rate between 2000-2010. There were 30,000 executives who earned $50,000 or more in 1955 (roughly $575,000 in today’s dollars).

“But unfortunately, historically at the federal level and at the state level, tax cuts have really disproportionately skewed to big corporations and to really wealthy individuals,” says Amber Wallin, Executive Director of the State Revenue Alliance. “There’s a pressing need to address those inequalities and build the future that we want to see.”

What happened?

Origins of the Anti-Tax Movement

In 1952, a man named A.J. Porth sued the federal government for the corporate payroll taxes he withheld from his employees’ paychecks. He argued that, on the grounds that this taxation was equivalent to slavery, the tax violated the 13th Amendment. He also argued, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, that the 16th Amendment (Congress’s power to collect income taxes) was unconstitutional and “put Americans into economic bondage to the international bankers” — as they note, “a thinly veiled anti-Semitic reference.”

His case was a dismal failure in the courts, but an anti-tax movement grew alongside him. That year, Ralph Gwinn, a congressman from New York, proposed the “Liberty Amendment,” a measure to repeal the federal income tax. The groups advancing a “rich people’s movement,” Isaac William Martin writes, were small at the time; the largest group, the Liberty Amendment Committee, peaked at 17,200 dues-paying members.

Powerful interests heard the message, according to Martin. In the West, ranchers and realtors saw a profit opportunity: limiting the power of the federal government could liberalize grazing leases or privatize public lands. In the South, proponents of the Liberty Amendment emphasized it would restore “States’ Rights,” particularly after the Supreme Court issued Brown v. Board of Education. By 1982, nine state legislatures would endorse a repeal to the income tax.

Repealing the income tax never amassed a winning coalition, but anti-tax advocacy mainstreamed. In 1978, former businessman and realtor lobbyist Howard Jarvis led the adoption of ballot initiative Proposition 13 in California, dubbed “The Tax Revolt.” Prop 13 capped property tax increases, and Jarvis’s campaign, said tax law scholar Michael Graetz in an interview, relied on coded racial language: “He always talked about us paying for them. We are paying the taxes, and they are getting the benefits.”