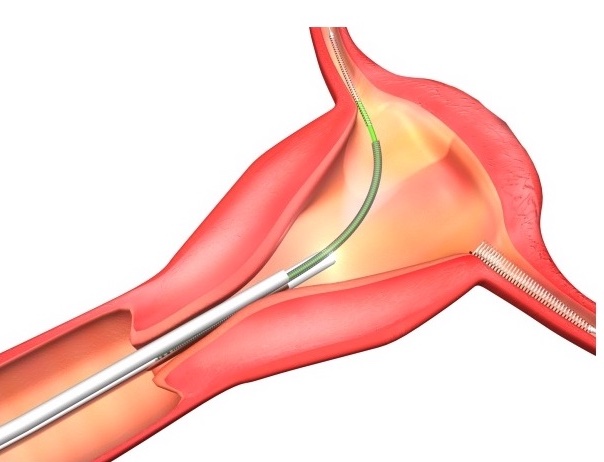

The lawsuits speak to a wider problem of an information gap between IUD users and the corporations that manufacture them. The risk of organ perforation has long been known as a possible side effect of IUD use. Perforation of the uterus with IUDs was first described in the 1930s. Those who experience organ perforation may feel persistent lower abdominal pain. But, often, perforation of the uterus can be asymptomatic, so cases are unidentified until months or many years after insertion. Many instances of perforation can lead to ectopic pregnancy.

Doctors can also play a critical role in encouraging patients to get IUDs while also obscuring information about their harmful side effects. Drug companies will often pay doctors, legally, to prescribe drugs and devices to their patients. In the case of IUDs, specifically, public reports reveal that in 2018 alone, Bayer paid at least $263,000 to over 7,000 doctors and that CooperSurgical paid at least $496,000 to over 1,700 doctors across the country.

IUD manufacturers’ provision of financial incentives to doctors to prescribe drugs have predictably ensured that prescription rates for these drugs increase. Doctors, moved by this financial incentive, may thus downplay side effects of IUDs to their patients so that their patients will be encouraged to use them. Corporate payouts can also encourage these doctors to re-prescribe IUDs even in cases where patients have previously experienced serious side effects from the devices. This widens the information gap between IUD manufacturers and IUD users, while also safeguarding IUD sales.

At the same time, some researchers emphasize that potential side effects like organ perforation do not “detract from the overall excellent safety records of IUDs.” But these reassurances are not enough to convince individuals like Gina Burg, Amber Espinosa-Jones, Katie Rainford, Raegan Carmon, and the thousands of others who have actually experienced egregious pain, complications, stress, and irreversible side effects from IUDs to continue to use them.

It is not uncommon for individuals to suffer major health complications from using implanted birth control devices. When the Dalkon Shield IUD hit the market in 1971, for instance, more than 200,000 users of the device suffered from pelvic inflammatory disease, infections, and other deadly complications due to the IUD’s design. Controversially, Bayer had paid $2.5 million to 11,850 doctors from August 2013 to December 2017 in consulting fees and similar services. The Dalkon Shield was not taken off the market until after 15 years of adverse reports. The device’s manufacturer, A.H. Robins Company, paid nearly $3 billion to victims.

Invented in 1968, the Dalkon Shield was made primarily of plastic and inserted into the uterus. Its pronged edges were meant to prevent the device from being expelled from the body. It also contained small amounts of copper that acted as spermicide, preventing sperm from fertilizing an egg.

Another IUD manufacturer G.D. Searle & Co. that produced the Copper-7 IUD similarly had to settle hundreds of claims in the late 1980s from individuals who alleged the IUD caused pelvic inflammation, ectopic pregnancies, perforation of the uterus, and infertility in some cases. After being one of the most widely used IUDs in the country, it was removed from the market 12 years after it was introduced.

Even more recently, Essure, a permanent birth control device manufactured by Bayer, made headlines for perforating users’ uteruses and fallopian tubes, and causing severe pain, ectopic pregnancies, and infertility. It was not until 16 years after the device was introduced into the market that the FDA put a black box warning on the product, noting that it could perforate the uterus or fallopian tubes. Bayer stopped selling Essure in 2018, and it announced that it would pay $1.6 billion to end nearly 39,000 Essure lawsuits involving women who claimed the birth control device caused serious health complications.

Past Essure users report that they are still experiencing complications even years after they had the device removed. Still, Bayer never recalled the device. Rather, throughout the controversy, Bayer maintained that its decision to discontinue Essure was purely financial, citing “inaccurate and misleading” publicity behind its plummeting sales. Is it a matter of time before the dangers of the IUDs on the market today match up to the dangers of the now defunct Dalkon Shield, Copper 7-IUD, and Essure devices?

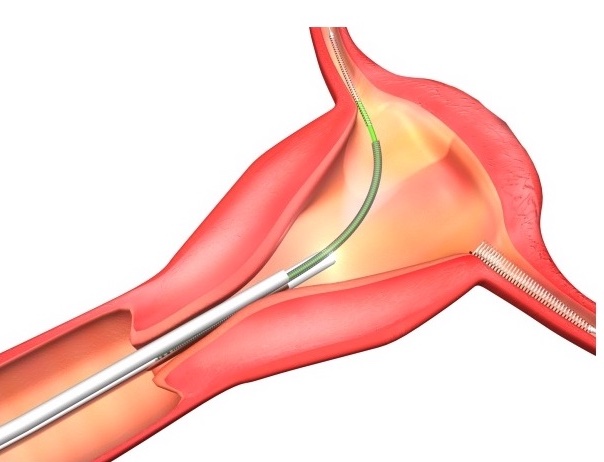

Essure was a permanently implanted birth control device that was made up of two nickel-titanium coils that doctors implanted into the fallopian tubes. Once in place, the coils block the passage of eggs into the uterus. Scar tissue gradually forms around the coils, sealing them in place.

Attorney Fidelma Fitzpatrick at Motley Rice, LLC represents victims of corporate malfeasance, including hundreds of women allegedly injured by medical devices like Essure who have initiated personal injury claims against device manufacturers. She also serves on the Plaintiff’s Executive Committee that will lead the national consolidation of cases for women who allege they suffered severe complications from the Paragard IUD.

“There is no question that women need and deserve safe and effective long-term contraceptive methods such as the IUD,” Fitzpatrick writes. “These devices can only be helpful if manufacturers are careful to go to every length necessary to make sure the benefits outweigh any risk. Unfortunately, that has not always been the case with IUDs and other forms of birth control.”

Underfunding of research in women’s health issues worsens the problem of manufacturer inattention to developing safer birth control products. Women’s health has been historically under-researched. From 1977 through 1993, the FDA excluded women of “child-bearing potential” from clinical trials, while a comparatively large amount of data was collected on the impact of various drugs and clinical trials on males. FDA’s rationale for this was that female and male bodies were generally the same and that hormonal fluctuations in women’s bodies would complicate analyses of clinical trials.

Despite the fact that women of “child-bearing potential” were allowed to be included in clinical trials following 1993, an absence of female participation in the trials and a loss of data on women’s health impacts continued. There was a clear need to conduct these clinical trials, where eight out of ten of the drugs removed from the U.S. market between 1997 and 2000 were withdrawn because of side effects that occurred mainly or exclusively in women. Between 2004 and 2013, women in the U.S. suffered more than 2 million drug-related adverse events, compared with 1.3 million for men.

“These devices can only be helpful if manufacturers are careful to go to every length necessary to make sure the benefits outweigh any risk. Unfortunately, that has not always been the case with IUDs and other forms of birth control.”

Correspondingly, studies suggest that, to this day, the National Institute of Health applies a disproportionate share of its resources to diseases that primarily affect men, at the expense of those that primarily affect women. One study noted that in nearly three-quarters of cases where a disease afflicts primarily one gender, the funding pattern favors males, in that either the disease affects more women and is underfunded, or the disease affects more men and is overfunded.

Women make up over half the U.S. population, make up 80 percent of buying and usage decisions in the healthcare industry, and make up 65 percent of the healthcare workforce. Yet, they are still very plainly underrepresented in healthcare leadership positions. Women only make up approximately 30 percent of C-suite teams and 13 percent of CEOs among healthcare companies.

The top ranks of the biotech and pharmaceutical industries are also overwhelmingly male, where men still account for 92 percent of the industries’ CEO roles among nearly 200 leading drug companies. Because most healthcare and pharmaceutical company leaders are men, these industries have less understanding of women’s health issues than they would have with more women in leadership roles. Disproportionate representation of men and gender bias within the healthcare industry has likely influenced the fact that women’s health issues remain underfunded and under-researched. And, harmoniously, it is no surprise that in this male-centric field, corporate manufacturers of birth control devices may likely have comparatively and systemically less incentive to spend their resources on developing better, safer devices for women.

Women make up over half the U.S. population, make up 80 percent of buying and usage decisions in the healthcare industry, and make up 65 percent of the healthcare workforce. Yet, they are still very plainly underrepresented in healthcare leadership positions.

Fitzpatrick writes that manufacturers have a responsibility to make sure that complete transparent information concerning all the risks and benefits about their birth control products is not denied to women. “Manufacturers must recognize the critical role they play in [women] making such a personal [family planning] decision and ensure that they are advocates for women’s health, not simply advocates for selling a product.”

But instead, corporate manufacturers of birth control devices aggravate the problem of gender bias within the healthcare industry. They contribute to the information gap by burying disclosures about the side effects of their products and providing money to doctors to emphasize their products’ overall safety. When doctors, IUD websites, and IUD marketing fail to make the risks of IUD use clear to consumers, who is to blame for the gap in information? Studies suggest that if health services and professionals provide timely and adequate information about the IUD, confidence in the IUD can be increased. That is, the level of users’ knowledge about the IUD was associated with their level of interest in using it. This consequently suggests that doctors have the power to provide adequate information about IUDs to users.

Corporate manufacturers of IUDs have thus unsurprisingly tried to shift the blame to doctors to absolve themselves of liability in IUD users’ failure to warn suits against them. This is a legal strategy known as the “learned intermediary doctrine.” The learned intermediary doctrine only requires that a manufacturer inform the gynecologist of the risks associated with the device, and that the gynecologist notify the patients of these risks through adequate informed consent. To satisfy the legal requirements of informed consent, a gynecologist must disclose to patients what a reasonable practitioner would consider pertinent to the discussion, as well as what a “prudent” patient would want to know to make a treatment decision.

“Manufacturers must recognize the critical role they play in [women] making such a personal [family planning] decision and ensure that they are advocates for women’s health, not simply advocates for selling a product.”

Corporate IUD manufacturers may also raise several defenses in failure to warn claims. One defense is the assumption of risk defense, where a corporation may claim that the consumer knew there was some inherent risk in using the IUD. In this way, the corporation would argue the assumption of risk on the IUD user’s part eliminates corporate liability.

Even where corporate manufacturers do not shift liability to doctors or raise other successful defenses, it can still be very difficult to hold them accountable in failure to warn lawsuits. This is because the law around these suits requires that plaintiffs prove the IUD, and not something else, directly caused the side effects they allegedly experienced.

Proving causation can be challenging in some cases–even in those where causation may seem obvious. In one such case, the plaintiff claimed her Paragard IUD broke off before or during removal, requiring her to surgically remove her uterus. She alleged this was due to a manufacturer defect and that causation was straightforward, as a juror could look at a broken IUD and “plainly see” that some error of the manufacturer caused the break. The court disagreed, deeming the claim too speculative.

Proving causation has also been an issue in IUD users’ lawsuits against manufacturers where the plaintiff’s alleged side effects from the IUD could be a result of other causes. This was the case when Mirena IUD users failed to convince the judge that they suffered from pseudotumor cerebri (PTC) because of their IUD, and not other causes. Moreover, proving causation has been an issue where individuals have initiated suit against Skyla IUD and Liletta IUD’s manufacturers, alleging that their IUD caused them to develop breast cancer.

Reports vary on whether there is a link between hormonal IUDs like Skyla, Liletta, and Mirena and increased risk of breast cancer. In IUD manufacturers’ favor, more data is likely needed to clearly establish a link between the two, in the face of outside potential causes of breast cancer, and other side effects. Thus, corporate manufacturers escape liability where there is not enough data on women’s health problems and their linkages to IUDs.

Corporate manufacturers further avoid accountability in these cases by pushing for settlements in IUD lawsuits. Conversation and media attention around IUD safety is quieted as victims are paid likely a fraction of what they could have otherwise won in court through trial, had they been able to take the risk that they would lose. This is especially true where these settlements have been confidential, so parties and their attorneys are prevented from disclosing details about the dispute. Corporate manufacturers of IUDs are thus able to continue selling their products and deny the causal connection between their products and the harm victims face, reflecting corporations’ commitment to not talk about the problem of IUD safety. Rather, corporate manufacturers of birth control devices often promote the narrative that their devices are safe overall and have maintained that their labels adequately warn users of the risks of their products amid suits against them.

As Fitzpatrick works on Paragard IUD lawsuits, she laments the problem of how to compensate victims properly for the harm they faced. “My heart breaks for these women, knowing that the damage can never be undone. They’re entitled to seek justice,” Fitzpatrick noted in a Motley Rice article.

Unfortunately, many IUD users have limited access to the legal system to hold corporate manufacturers accountable for their suffering. Legal fees are cost prohibitive to many victims who might have otherwise wanted to initiate suit against IUD manufacturers. Additionally, victims only have a limited amount of time to initiate suit against IUD manufacturers due to applicable statutes of limitations. Some victims are thus unable to find lawyers to take on their cases in time to initiate suit.

For victims like Gina Burg, who have been unsuccessful thus far in finding a lawyer to represent them, it may be impossible to ever demand accountability from IUD manufacturers. “I haven’t even entertained the thought [of what corporate accountability would look like to me] because I’m always told no,” Burg said. “More than anything, I’d just like for more people to be aware of it and to not get the IUD –it’s not safe.”

“I haven’t even entertained the thought [of what corporate accountability would look like to me] because I’m always told no,”

The FDA’s role in the controversy over IUD safety is especially important to consider when it comes to these cases. It was not until after the Dalkon Shield caused thousands of IUD users to suffer reproductive health impacts, that the FDA was finally authorized to regulate IUDs in 1976. The approval process for these devices can take three-to-seven years to bring from concept to market and generally do not require clinical trials. Because of the costliness of FDA market approval, incumbent corporate IUD manufacturers are said to enjoy a monopoly in the U.S. on the IUD market. The FDA’s current regulatory process for market approval of IUDs therefore does not support the development of safer birth control devices by additional companies. The U.S. reportedly has fewer types of IUDs than other countries. Because there are scarce comparable available products to IUDs on the market, individuals seeking birth control devices will likely continue to utilize IUDs.

Additionally, there is a question of whether the FDA is doing enough to require that IUD manufacturers adequately disclose information about side effects of the IUD to potential users. In 1977, the FDA initially required that IUD manufacturers provide prospective IUD users with information that tells them in plain language what the benefits and risks are of the IUDs.

Today, the FDA has the power to require that IUD manufacturers issue warning labels on their products and to conduct multidisciplinary review and evaluation of IUDs. For instance, the FDA has accused Mirena IUD manufacturer Bayer of overstating the effectiveness of the IUD, downplaying the serious health risks of its product, and failing to communicate proper risk information to women and their doctors. The FDA has also instructed IUD manufacturers on how to word their warning labels. For example, where Bayer wanted to note on the Mirena IUD label that organ perforation “may occur rarely, most often during insertion…”, the FDA recommended that Bayer remove the words “rarely” and “most often”.

As of early 2022, the FDA has received nearly 45,000 adverse reports associated with the Paragard IUD. The FDA has also received nearly 50,000 reports of serious side effects associated with the Mirena IUD including expulsion of the device, migration of the IUD, bleeding, hospitalization, and 50 deaths. Still, the agency has not made moves to require more from IUD manufacturers. According to the FDA, the number of adverse reports from IUD users “does not necessarily represent individual patient cases,” because the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database can duplicate or miscode reports.

Presently, the FDA considers that the currently approved drug for Paragard and Mirena IUDs contains the necessary information for safe and effective use of the IUDs.

The FDA has explained that it “routinely monitors post-marketing safety data for approved drugs…through multiple sources including, but not limited to, adverse event reports filed with the FDA through [the] FAERS database, published literature, and periodic safety reports submitted by marketing application holders, and the FDA takes regulatory action (e.g., requesting or requiring revisions to product labeling, communicating new safety information to the public) as appropriate.”

Presently, the FDA considers that the currently approved drug for Paragard and Mirena IUDs contains the necessary information for safe and effective use of the IUDs. Not all IUD users would agree – especially as they continue to experience negative side effects that they were not warned about.

Nevertheless, after decades on the market, it appears that the IUD is not going anywhere anytime soon. In 2017, Planned Parenthood saw a 900 percent increase in patients seeking IUDs, and the number of women visiting their doctors about IUDs increased by nearly 19 percent. The demand is anticipated, as the IUD is marketed as one of the most effective contraceptives, preventing pregnancy in 99 percent of women who use it over the course of a year. The need for access to birth control devices fuels demand for IUDs where only a few corporate manufacturers monopolize the market. Individuals who need birth control are consequently forced to resort to the options available to them–options that may severely worsen their quality of life.

Over the years, Bayer remains the corporate giant in this space, with its IUDs netting the company $900 million in the U.S. in 2016 and continually being among the company’s 15 best-selling drugs for the past decade. Bayer has striven to maintain its market dominance, urging the FDA to require that proposed generic devices undergo comprehensive clinical testing rather than lab experiments to prove their equivalence to Bayer’s IUDs.

There can be no demand for new birth control products where the FDA’s regulatory scheme supplement only a few IUD manufacturers’ monopoly over the market and does not require more extensive disclosure of harmful side effects of IUDs. The popular narrative that the market will correct itself–that it will respond to the demands of consumers and that consumers can put their faith in it–is prevalent. But how can IUD users who have suffered harmful side effects from IUDs put their faith in the market responding to their demands if there is no way for them to make those demands to begin with?

It appears that when it comes to IUD production, corporate manufacturers participate in a healthcare industry market that reproduces gender bias against women. These manufacturers fail to adequately communicate the risks of using these health drugs and devices. The healthcare and pharmaceutical industry remain largely led by men who have historically paid less attention to researching women’s health and developing women’s health products that are completely safe. The legal system and regulatory systems in place shield manufacturers from liability and fail to provide avenues for reprieve to all.

[H]ow can IUD users who have suffered harmful side effects from IUDs put their faith in the market responding to their demands if there is no way for them to make those demands to begin with?

As the results of pending Mirena and Paragard IUD cases come to fruition, it is not clear that victims will see more corporate accountability when it comes to IUD safety. For now, the burden is shifted to victims of IUDs to spread awareness of their experiences. As manufacturers avoid blame, and as current and potential IUD users continue to remain in the dark about many of the side effects of IUDs, awareness of IUD safety risks tends to spread where IUD users advocate for themselves.

“Women have become vocal advocates for safe and effective birth control options, which has led to an increased awareness of the risks associated with IUDs and other long-term birth control devices,” Fidelma Fitzpatrick wrote.

“Everything I hear about [the IUD] is very anecdotal and it’s not something you look into once you’ve experienced it yourself because you wouldn’t know to,”

Gina Burg explained that there are challenges with women being their own advocates in this space. “We’re not supposed to talk about [women’s healthcare],” Burg said. “We don’t talk about [it]. It’s still considered taboo.”

“Everything I hear about [the IUD] is very anecdotal and it’s not something you look into once you’ve experienced it yourself because you wouldn’t know to,” Katie Rainford said in the same vein. “Your doctor is not explaining [it] to you and the reading materials [they give you] are not explaining [it] to you…It all seems very simple. And it’s not.”