The Costs of Carceral Communications: How a Prison Telecommunications Company Exploits Incarcerated People and Their Loved Ones

Prison telecommunications provider, Securus, gouges incarcerated people and their families.

Adriel Williams

June 27, 2022

Jeffrey* returned to his prison cell in a state of panic. No matter how many times he checked his prison-provided tablet, his email inbox remained empty.

Jeffrey, an incarcerated individual at a maximum-security New York state prison, emailed his mother, Stephanie, nine days ago. Jeffrey expected a response by now. Stephanie, the light of Jeffrey’s life, had never taken this long to respond.

Stephanie is the only person who has stood by Jeffrey during his 40-year prison sentence. Reuniting with Stephanie after completing his prison sentence gets Jeffrey through the day. He has worked tirelessly to rehabilitate himself and earn his bachelor’s degree to make Stephanie proud. But as the hours passed, Jeffrey worried that his sick mother had another health scare related to her diabetes and high blood pressure.

Frantic, Jeffrey didn’t know what to do. He didn’t have enough credit on his prison phone account to call Stephanie, so that was out of the question. Maybe another guy has enough phone credit, he thought to himself. But he ruled out that idea given the prison policy forbidding shared property. He couldn’t risk getting caught. If the prison caught wind of Jeffrey using someone else’s tablet, he would surely lose his job and jeopardize the progress he had made obtaining his bachelor’s degree. The prevalence of COVID-19 among the prison population also convinced him that this wasn’t a good idea. But then an idea popped into his head: Father John.

Jeffrey had befriended the prison chaplain, Father John, who had helped Jeffrey become a born-again catholic. Father John contacted Stephanie the last time she had a health scare. Jeffrey thought to himself, I bet he’ll help me again. But before Jeffrey could act on his plan, his tablet lit up.

Jeffrey scurried over to the other side of his cell, anxiously waiting for the full message to load. Come on, come on, he thought to himself. And then, the email finally loaded.

It was a five-word message from Stephanie. To Jeffrey’s relief, Stephanie was healthy and well. Scrutinizing the message more carefully, Jeffrey realized Stephanie sent this five-word email eight days ago. Yet he just received it now. Jeffrey collapsed from exhaustion and frustratedly sighed to himself one word: “JPay.”

Jeffrey collapsed from exhaustion and frustratedly sighed to himself one word: “JPay.”

Jeffrey’s difficulty communicating with his mother isn’t unique. Incarcerated people across the U.S. are at the mercy of prison telecommunications provider JPay Inc., the Florida-based corporation that provides communication and entertainment services to incarcerated people. JPay monopolizes how incarcerated people communicate with the outside world by centralizing phone call, email, and entertainment services in JPay devices. JPay makes it unbelievably difficult for incarcerated people to maintain regular contact with their loved ones because of its astronomically high prices and lackluster service.

Jeffrey is one of over a million incarcerated people served by JPay. JPay is the subsidiary of the Dallas-based prison communications firm Securus Technologies, Inc.

Incarcerated people and their loved ones often know JPay best since it’s the technology platform they use to communicate. But Securus is the actual corporation contracting with states and counties putting JPay technology in prisons. Securus, however, does offer its own devices for incarcerated people to call and video chat on.

__________

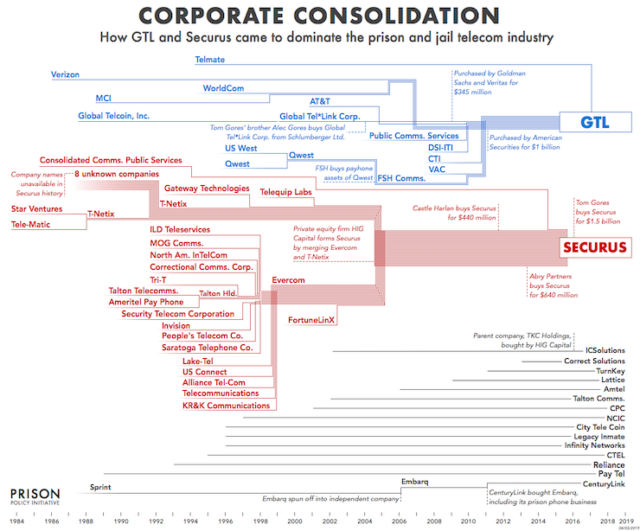

Securus is a giant. Securus and its main competitor Global Tel Link (GTL) collectively control up to 73 percent of the prison telecom market.

Since the 1980s, Securus has steadily acquired its competitors and increased its market share. Source: Prison Policy Initiative.

Whether it’s phone calls, emails, music, or movies, Securus is a one-stop shop for incarcerated people’s entertainment and contact with the outside world. To the unsuspecting observer, Securus seems like a steal. Judging from its press releases boasting unprecedentedly low call costs, flexible subscription plans, and corporate responsibility, Securus has it all. But taking a deeper look reveals one major catch: ancillary fees.

Ancillary fees are costs associated with depositing money into a JPay account, withdrawing money from a JPay account, and much more. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) labeled these ancillary fees a “chief source of consumer abuse.”

Jeffrey told me the costs of these ancillary fees make it difficult to communicate with his mother. “If you have a phone account, [and] you want to add money to it, they charge you. So, if my mom wants to put money on the phone [account] and only has $20, only $12.50 goes in the account…they charge you $7.50. If the account is already open, why do you have to pay to put money in?” he wondered.

These ancillary fees are independent of the more visible problem with prison phone calls: the prices of calls themselves. The costs of prison calls vary significantly. Securus does not maintain a base rate.

Wanda Bertram of the Prison Policy Initiative — a criminal justice thinktank — explained the variance to me. “If you live in Dallas and have a loved one locked up in the Dallas County jail system, you pay about $0.01 a minute with Securus. But if you look nationally, the average cost of a 15-minute county jail call is $5.00, compared to $0.15 in Dallas. How is that fair?”

A recent case in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled that the FCC lacks authority to cap intra-state call rates. This ruling gave states free rein to jack up the prices they can charge incarcerated people, which Securus was eager to oblige.

In Kentucky for instance, the average price of a 15-minute prison call is $5.70. And in Arkansas, incarcerated people typically pay $4.80 for a 15-minute call. The prisons in these two states use Securus products for calls, just like Dallas. But unlike the prisons in Dallas, the correctional facilities in Kentucky and Arkansas refused to negotiate for the lowest possible costs.

Maya Ragsdale, the chief counsel of Worth Rises, an advocacy group for prison justice, told me that companies like Securus maintain a telecommunications monopoly on a captive audience. “The prison decides on the contract it enters into with a private telecoms company and the only option [an incarcerated person] has is to use that provider and to be charged those rates.” Ms. Ragsdale said.

“The prison decides on the contract it enters into with a private telecoms company and the only option [an incarcerated person] has is to use that provider and to be charged those rates.”

Each penny an incarcerated individual must spend on services like Securus is significant. “I make $15.50 every two weeks, and $0.25 an hour. . . . I would spend more with JPay if their prices were reasonable,” Jeffrey told me.

To send an email on a Securus device, Securus tacks on another fee called a “stamp” that incarcerated people and their families must pay for. Jeffrey told me that each stamp costs $0.25. It takes Jeffrey an hour of work to make that much.

Troublingly, making outside communication more difficult for incarcerated people like Jeffrey leads to worse outcomes for incarcerated individuals and their families. Research shows that incarcerated people who have regular phone contact with family members are less likely to be reincarcerated within five years after their release. Additionally, research demonstrates that incarcerated people who maintain relationships with family members are more likely to be employed after leaving prison, and less likely to abuse drugs.

Lisa, a mental health professional at the prison where Jeffrey is incarcerated, runs a program that helps incarcerated people suffering from mental illnesses prepare to return to their communities. She knows firsthand how important phone calls are for incarcerated people as they transition back to their communities.

“There is nothing more important than connecting with the people [incarcerated people] are going home to. There are guys who will be living with their wives when they get out, but because they can’t afford the phone calls, they have no contact with the people they’re expected to bond with to be rehabilitated,” she told me.

“There are guys who will be living with their wives when they get out, but because they can’t afford the phone calls, they have no contact with the people they’re expected to bond with to be rehabilitated.”

High-powered government officials have also taken notice of these high prices. In a 2015 statement, former FCC Commissioner, Mignon Clyburn, expressed concern over the costs of phone calls within prisons. “Meaningful communication beyond prison walls helps to promote rehabilitation and reduce recidivism… In a nation as great as ours, there is no legitimate reason why anyone else should ever again be forced to make these levels of sacrifices, to stay connected,” she said.

Rehabilitation and recidivism represent just one side of the coin. Maintaining the family relationship in and of itself is important to both incarcerated people and their families. Phone calls and mail help with that. Studies have shown that parent-child relationships improve between an incarcerated person and their child when they have frequent contact through mail or phones.

However, in states like Florida, Securus’s inconsistent email service is the only mail service incarcerated Floridians have left. A recently finalized rule by the Florida Department of Corrections banned all paper mail. Now, mail services are exclusively completed through JPay’s email services. Alarmingly, this is the same delayed email service that resulted in Jeffrey receiving an email eight days late from his sick mother — a delay so stressful that Jeffrey had to be rushed to the prison infirmary because his blood pressure got so high.

Lisa explained to me that Jeffrey’s negative experience using JPay’s email service isn’t unusual. Other incarcerated people she knows suffer from JPay’s lackluster service. “There is one man who has major depression trying to rekindle his relationship with his daughter. So, he’ll send emails [to her]. I eventually spoke with [his daughter] and she said she wasn’t receiving the emails. He thought she wasn’t writing him back because she didn’t want to, but the reality was that the [JPay] emails were not going through.”

__________

Across the country in Washington state, Leilani Creed is frustrated. She has spent days trying to figure out the best way to express her exasperation with JPay. After some time thinking it over, it finally came to her: an online petition.

Ms. Creed’s completed petition contains the headline, “DEMAND that JPAY.COM and CEO Errol Feldman STOP robbing families.” The petition closes with the following message, “JPAY AND IT’S CEOs and owner have the market cornered and are taking advantage of families. The importance of staying in contact with your loved one is very important.”

As a single mother whose son — Damian — has been in Washington State Penitentiary (referred to by local Washingtonians as “Walla Walla”) for a decade, Ms. Creed is well-acquainted with the prison industry and the difficulties associated with it. “I’m the only one supporting my son, financially and mentally,” Ms. Creed told me. “I work full time and I have five other kids, but he’s the one who needs the most attention.”

Leilani Creed and her son Damian who is serving a sentence at Washington State Penitentiary. Source: Leilani Creed

But communicating with Damian isn’t easy. In Walla Walla prison incarcerated people and their loved ones must use Securus’s subsidiary, JPay, as well as another provider called ConnectNetwork to speak on the phone. But often, the services don’t work consistently enough to allow Ms. Creed or Damian to use them. And when the services fail, Ms. Creed can’t communicate with Damian.

“The calls are dropped a lot, there’s a lot of static, and I get angry because I can’t hear [Damian] and he can’t hear me. He’ll have to call me back. And then that’s more money. If you ask [JPay] for a refund, you may get it, or you may not.”

“I’m the only one supporting my son, financially and mentally,” Ms. Creed told me. “I work full time and I have five other kids, but he’s the one who needs the most attention.”

This lackluster service is even more problematic when considering Securus’s price increases. “[Securus] raised their prices. So, if I add $10.00 to my son’s [phone account], it costs [me] $12.95,” Ms. Creed told me. These “insane” prices, as she calls them, prompted her to create a petition.

“I was hoping to stop JPay from raising their prices just because they can — I was hoping they’d take notice and stop taking advantage of families who work hard for their money,” she told me.

Ms. Creed started a Facebook support group to provide families and formerly incarcerated people a space for resources that help incarcerated people succeed on the outside. The group has allowed her to form a community. She told me, “I have personal friends who have kids who are incarcerated. Many [people] struggle with money to come up with the ten bucks for JPay. Everyone feels outraged and frustrated.”

__________

When billionaire Tom Gores had his private equity fund buy JPay’s parent company, Securus, he viewed the purchase as a “sound investment.” In effect, his goal was to make as much money as possible. This perspective reflects the conventional view of corporate law’s purpose: shareholder primacy.

Shareholder primacy requires maximizing profits for shareholders rather than considering the interests of other stakeholders (consumers, employees, the environment etc.) affected by corporate activity. The consequences of viewing the purchase from this perspective, however, creates unjust incentives.

Maya Ragsdale explained to me what these incentives mean for Securus’s business model. “Securus’[s]…profit model is literally based off the number of people incarcerated; the more people that are locked up, the more people use their services and the more money they are making.”

“Securus’[s]…profit model is literally based off the number of people incarcerated; the more people that are locked up, the more people use their services and the more money they are making.”

Securus has begun to take notice that stakeholders are aware of its controversial business practices. In response, the corporation has curated a public narrative that it no longer prioritizes profit maximization over the interests of stakeholders like incarcerated individuals and their families. Securus now publicizes that it provides incarcerated people with access to the outside world at low costs.

Jade Trombetta, spokesperson of Securus, explained to me that “The exaggerated stories being recycled about us, simply don’t reflect the work over the last few years.” Ms. Trombetta touted the tablets that incarcerated people like Jeffrey and Damian now have access to. She told me that Securus has put 420,000 tablets in prisons across the country.

She explained, “We’ve invested hundreds of millions of dollars out of pocket each year in technology…and infrastructure to put tablet-based platforms into the hands of the incarcerated.”

Billionaire Tom Gores, whose private equity fund owns Securus, throwing shirts into the crowd at a Detroit Pistons game. Source: Eric Lacy/mlive.com

Ms. Trombetta also pointed out that Securus has reduced its average call price per minute to $0.11.

“Those are costs, not profits,” Ms. Trombetta told me.

It isn’t just Securus employees hyping the company’s narrative that it delivers quality, affordable services. Another prevailing account in some activist circles is that Securus’s services must remain in the hands of corporations like Securus.

A recent article by civil rights leader Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr. laid out his concerns about Securus’s expensive services. Nevertheless, Dr. Chavis praised Securus’s efforts of helping incarcerated people. He observed, “Securus seems to be making good on its promises” of operating for the benefit of incarcerated people. And at the end of his article, he noted that while Securus isn’t ideal, it’s the best option available. Dr. Chavis wrote, “The solution is not, as some have suggested, to eliminate these companies altogether. The services they provide are needed, and few believe they could be offered at the same quality or efficiency by the public sector.”

The upshot of Dr. Chavis’s article is that he legitimates a corporation by buying into the oft-cited narrative that public sector interference with the free market is misguided, despite Dr. Chavis’s failure to provide evidence of this in Securus’s case. In effect, Dr. Chavis adopts Securus’s narrative that it provides a service guided by the interests of incarcerated people, for the benefit of incarcerated people.

Carefully unpacking this narrative leads an observer to arrive at different conclusions, however. While Securus and certain activists may see these corporatized telecom services as legitimate and just, the truth lies much deeper. Nothing requires these prison telecom services to remain corporatized, prohibitively expensive, and faulty, even if Securus would have you believe so. Securus may portray itself as a benevolent service provider, but that portrayal could not be further from the truth.

__________

Three years ago, when Lisa heard that her incarcerated patients were receiving free tablets from Securus, she thought it was a joke. Incarcerated people do not have access to the internet in the prison where Lisa works, so she wondered why incarcerated people would be getting tablets to use inaccessible services.

“We heard these rumors that inmates were getting tablets. For the longest time we didn’t believe it. It seemed too good to be true. But one day I saw all these salespeople,” Lisa told me.

New York is one of several states that has received “free” Securus tablets for its incarcerated population. New York has received about 50,000 of the 420,000 tablets that Securus has distributed.

This tablet initiative has prompted Securus to lean into the narrative that it’s a benevolent service provider. The company has even convinced activists like Dr. Chavis about the company’s generosity and legitimacy as a charitable service provider.

In reality, however, the “benevolence” of free tablets is misleading. Lisa explained the hidden consequences of Securus corporatizing prison communication services. “We spent a week, almost eight hours a day, creating codes and passwords for use of the tablets. It was unbelievably difficult, especially for the [incarcerated people] . . . . Nothing was explained to the inmates or us, and suddenly our old communication systems didn’t work.”

Troublingly, the tablets provided at an incarcerated person’s prison of origin may not follow him to another prison if he transfers. Jeffrey is one of many incarcerated individuals who has been transferred across prisons, and risks losing his only source of communication with his mother. “Theoretically, each inmate is given a tablet and if they move to different prisons, the tablet is supposed to follow them. But I would say at least half of the inmates I know, for whatever reason, when they move from one prison to another, their tablets don’t come with them,” Lisa told me.

To receive a new tablet, incarcerated people then must send a grievance to JPay. But responses from JPay can take months. Jeffrey told me one grievance he entered took two months to receive a response. Because JPay typically centralizes all communication services in its tablets, incarcerated people like Jeffrey find themselves in a state of limbo waiting to hear back from JPay with no way to speak with their loved ones.

“There is no way to communicate with anyone on the outside because they don’t have a tablet. If [the grievance process] doesn’t work, they have to write a letter to the designated prison official, who often doesn’t respond. And there’s often no way [the tablets] can be replaced,”

“There is no way to communicate with anyone on the outside because they don’t have a tablet. If [the grievance process] doesn’t work, they have to write a letter to the designated prison official, who often doesn’t respond. And there’s often no way [the tablets] can be replaced,” Lisa told me.

Jeffrey believes that Securus’s tablet initiative is entirely driven by profits rather than benefitting the incarcerated population. “They can definitely cut their prices in half and still make a good profit,” he told me. The revenue reports back up Jeffrey’s assertion.

Despite Ms. Trombetta’s claims that Securus is operating at a loss by providing “free” tablets, Securus is cashing in with millions in profits from its tablet program. The New York Department of Corrections reported that Securus is projected to reap an $8.8 million dollar profit over five years from the money incarcerated people and their families spend on tablet services.

The New York Department of Corrections reported that Securus is projected to reap an $8.8 million dollar profit over five years from the money incarcerated people and their families spend on tablet services.

The more money family members deposit into their loved one’s Securus account, the more the corporation takes. As Jeffrey told me, “The more you send, the more they charge.”

Recall that Securus takes $7.50 of the $20.00 Jeffrey’s mom sends him for phone calls. And it costs Ms. Creed $7.95 to send Damian $20.00.

This of course does not account for other services like movies and music that incarcerated people must rely on their Securus-provided tablets for. “They charge anywhere from $3.99 to $7.99 to rent a movie for 48 hours,” Jeffrey told me. “Most of the games they sell us you can get the same version for free on a phone.”

Ms. Bertram also believes that Securus’s narrative about prioritizing people over profits is not borne out from the data. “The extraneous fees and what they call ‘taxes’ that these corporations impose…exploit incarcerated people and their families for profit.”

The disparity in phone call prices among the prisons that Securus negotiates with also raises doubts if the corporation is practicing the corporate social responsibility it boasts about. The current cost of a 15-minute call in Albany County jail — a jail that Securus contracts with — is $7.50. But the average cost of a 15-minute call in the New York state prisons that Securus contracts with is as low as $0.64.

“If you are incarcerated in one place, you have a relatively reasonable phone rate. But if you’re incarcerated anywhere else, you have this other rate. It shows that when Securus says it’s doing all that it can to bring down these phone rates, it’s completely disingenuous,” Ms. Bertram told me.

The effects of these disparities can have devastating impacts on families. Because families of incarcerated people are disproportionately low-income earners, the high prices that Securus charges can leave families in financial ruin. The FCC reported that 34 percent of families go into debt to keep in contact with their incarcerated loved ones.

The FCC reported that 34 percent of families go into debt to keep in contact with their incarcerated loved ones.

Financial difficulties hit families especially hard during the COVID-19 pandemic when prisons suspended in-person visitations, and families had to spend even more on Securus services to speak with their incarcerated loved ones.

Ms. Bertram explained that families of incarcerated people had to make extraordinary sacrifices just to afford Securus’s services when COVID-19 hit. “During the pandemic, I’ve heard from a lot of families of incarcerated people. I’ve heard [families say], ‘I don’t know how I’m going to put food on the table; I’ve refinanced my house, I’ve sold my car.’”

Securus’s business practices lend further credence to skeptics of environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG). ESG is the form of corporate governance that purports to advance social goals beyond maximizing shareholder profits; it considers the impact on the environment, employees, and consumers. ESG has become a trendy commitment that corporations like Securus claims it subscribes to, but often falls short of achieving.

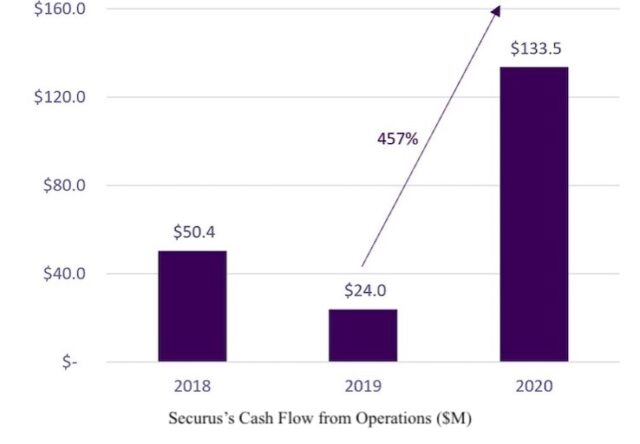

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Securus experienced unprecedented growth. And while Securus decreased its spending on tablet technologies and services for its incarcerated population, it was experiencing record-level profits from that same population.

Securus’s net cash flow from operating activities grew five-fold from 2019 to 2020, even though Securus spokespeople say Securus is sacrificing profits from its “benevolent” business practices. Source: Worth Rises

Importantly, Securus’s net cash flow — one of the metrics Ms. Trombetta claimed suffered from Securus’s “free” tablet initiative — increased fivefold to $133.5 million dollars. The company’s EBITDA also climbed 41 percent to a whopping $209.2 million. And Tom Gores, the billionaire whose private equity fund purchased Securus, paid his private equity fund 12 million dollars from these earnings.

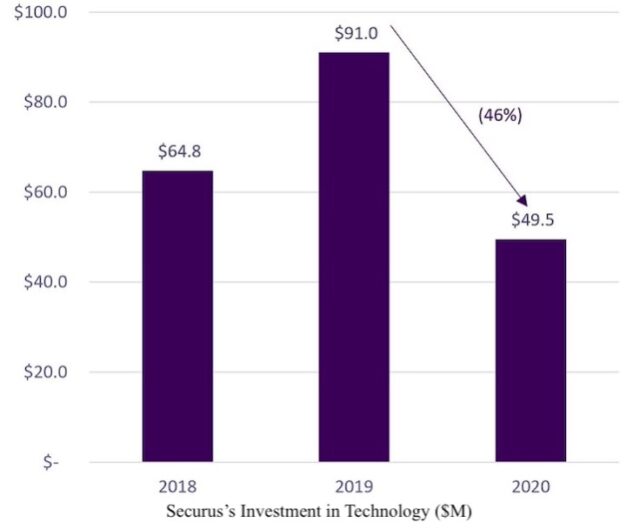

In a blow to incarcerated people, Securus decreased its investment in technology by 46 percent from 2019 to 2020. This statistic is especially surprising considering the disproportionate reliance on technology services like tablets among the incarcerated population during the COVID-19 pandemic. These technology services became increasingly important when incarcerated individuals like Jeffrey were stuck in their cells with no other way to pass the time. This decrease in technology investment corresponded with a 9 percent increase in payments to Platinum Equity, the private equity fund that owns Securus.

Securus spent nearly 50 percent less on technology for its incarcerated population in 2020, even though its profits soared to record levels and its net cash flow increased by over 450 percent. Source: Worth Rises

As a result, while Securus decreased its spending on tablet technology infrastructure and services for its incarcerated population, it was experiencing record-level profits from that same population. These statistics call into question whether Securus is actually considering the interests of other stakeholders as it claims it does.

In other words, statements from Mr. Gores and Ms. Trombetta claiming Securus is increasing its investment in its technology infrastructure are not borne out from the data.

Corporate law professor Lucian Bebchuk of Harvard Law School is a known critic of ESG and recently observed “The illusory promise of stakeholderism… obscure[s] the critical need for external interventions to protect stakeholders via legislation, regulation, and policy design.” This apt quote squarely applies to Securus and the misleading narrative it has created that has taken root in social circles of all kinds.

But while the observation by Professor Bebchuk is sound in the case of Securus, legislators must be careful. If they aren’t, they may begin to serve the very corporations they’re supposed to regulate, and become “captured.”

__________

Theories relating to government “capture” are not new. Economist George Stigler popularized the phrase in 1971. Capture refers to the idea that governments issue policies or regulations that become coopted to serve certain commercial or corporate influences rather than the consumers these policies are supposed to protect. Carefully reading a contract between a local government and Securus reveals the potential for coopted regulation.

Contracts between local governments and Securus regularly span 100 pages. In between the impenetrable “legalese” and jargon lies a troubling provision found in many of these agreements: commissions.

Commissions are fees that contractors like Securus pay to state and local governments from the revenue Securus makes off incarcerated people. Commissions are effectively kickbacks paid to governments for letting corporations like Securus install their technology in government prisons.

Ms. Ragsdale explained the system to me. “[Say] a company enters into a contract with Boston. In that contract, it will specify that the city of Boston is receiving 60 percent of the revenue generated from the [prison] phone calls. [The corporation] will receive the other 40 percent. What that does is incentivize local government[s] and state governments to enter into contracts with these private telecoms companies that charge the highest rate possible rather than the lowest rate possible.”

Ms. Ragsdale’s example actually low-balls the percentage that many states earn from these kickbacks. For instance, Securus’s 2020 contract with the Arkansas Department of Corrections provided that 79 percent of Securus’s revenue from incarcerated Arkansans went to the Arkansas government. Louisiana’s contract with Securus results in 70 percent of phone call revenue from incarcerated Louisianians going to the state of Louisiana.

Alaska takes 94 percent of Securus’s revenue that the company extracts from incarcerated Alaskans. Alaska garnered more than 1.5 million dollars from Securus products in 2020.

And the kickbacks get more extreme than that. Alaska takes 94 percent of Securus’s revenue that the company extracts from incarcerated Alaskans. Alaska garnered more than 1.5 million dollars from Securus products in 2020.

Securus spokesperson Jade Trombetta conceded that commissions are a problem. “Is there a challenge nationwide with commissions? Yes—we agree! In fact [we] oppose commissions—and that differentiates us from most competitors…and we’ve been public about opposing commissions,” Ms. Trombetta told me.

This statement, however, is inconsistent with how Securus conducts business with state and local governments. Many of the negotiated contracts remain in place regardless of what Securus may or may not say. For instance, Plymouth County Jail in Massachusetts receives up to 80 percent of Securus’s revenue from incarcerated people in the county through 2023. Essex County Jail, also in Massachusetts, has a commission-based contract effective through 2028, and receives 35 percent of Securus’s revenue made from its incarcerated population. And Middlesex County Jail reaps 32 percent of Securus’s revenue from its incarcerated population through 2025.

The continued use of commission-based contracts coupled with Securus’s public opposition to commissions is one reason why Wanda Bertram believes Securus is being “disingenuous” when it proclaims that its corporate governance considers the interests of incarcerated people. Securus’s public feel-good narrative obfuscates the corporate damage it’s doing to its consumer base by gouging incarcerated people and their families at every step.

These contracts create a unified interest between local governments and corporations like Securus: profit maximization. “To plug their budgets, there is this collusion between the private industry and these local governments,” Ms. Ragsdale told me. “Incarcerated people are a captive consumer market, and as a result, they’re completely vulnerable to what the local government and these private companies agree to on their behalf.”

“Incarcerated people are a captive consumer market, and as a result, they’re completely vulnerable to what the local government and these private companies agree to on their behalf.”

As discussed earlier, “captured” institutions are not a new concept. The effects of the so-called revolving door between government and the private sector is one such example critics cite, described by Judge Frank Easterbrook in 1986.

The difference in this case, however, is the clear and unmistakable connection between how use of each Securus product directly adds to a local government’s budget. When local governments receive commissions and create policies regulating access to Securus devices that supposedly increase incarcerated people’s access to the outside world, governments necessarily profit from each call made.

Whether the local governments know it or not, their interests become aligned with the corporation and end up serving Securus’s goals of maximizing shareholder value.