The Mighty Men: Enron

The Post-Mortem: A Column of Corporate Catastrophes

Jessica Graham

October 14, 2023

COLUMN ONE

“I had all my savings, everything in Enron stock, I lost $1.3 million. It was from rags to riches back to rags.”

I would be remiss not to start with the greatest corporate catastrophe of the 21st century: Enron. It’s now been over two decades since Enron’s collapse, but the corporation still serves as a building block in analyzing more contemporary corporate missteps. The above quote is from Charles Prestwood, a former Enron employee who had lost everything in its collapse. Prestwood was not an executive or high-ranking member of the corporation. He was one of hundreds of Enron employees who lost their jobs, their life savings, and their retirement in one fatal swoop.

Enron was founded in 1985, the result of a merger between two natural gas companies. When Congress deregulated the sale of natural gas, Enron transformed into a gas trading company—meaning it acted as a middleman between energy production companies and their consumers. In Enron executives’ view, it became a “gas bank,” buying low from producers and selling high to consumers. They were so good at it, in fact, that they began trading all sorts of things: electricity, paper, broadband, you name it.

The idea was the birthchild of Jeff Skilling, a young “hotshot” who then became the CEO of Enron. It was Skilling’s ideas and cultures that molded Enron into the bravado-seeking, masculine stereotype that it was. As Karl Klicker, a training manager at Enron, told the Wall Street Journal: “There were, like 25 Ferraris and Maseratis and Bentleys lined up on bonus baby row. And I thought, who works here? This is crazy. And what I found out later was if you’re a 26-year-old Stanford MBA and you make a billion-dollar deal, you get a million-dollar bonus.” Skilling, maybe in an attempt to show younger employees the ‘good life,’ or, maybe even just to gauge their personalities, also organized what he called “mighty man trips”—outlandish excursions including bug-eating, Land Cruiser racing, and other ‘manly’ activities. Compensating for something? Perhaps.

“There were, like 25 Ferraris and Maseratis and Bentleys lined up on bonus baby row. And I thought, who works here? This is crazy. And what I found out later was if you’re a 26-year-old Stanford MBA and you make a billion-dollar deal, you get a million-dollar bonus.”

Regardless of his reasoning, this was the energy and culture that Skilling cultivated at Enron. It wasn’t just one man’s doing, though. Many point to Andy Fastow, Enron’s long-time CFO, for the bulk of the downfall. There was also Ken Lay, who was a founder, chairman, and even served as a CEO—but swore his innocence until his death in 2006.

So, what exactly happened at Enron? The full story is much too winding and complex for this platform, but allow me to provide you the basics (if you’re interested in more, the Wall Street Journal’s Bad Bets Season 1 provides a great picture of the astonishing collapse).

In short, Enron took Skilling’s energy a bit too much to heart, getting greedy and overstretching their finances through some very tricky financial engineering (meaning, basically, playing with the books and transactions to boost their profits without actually making more money). This is where Andy Fastow comes in. Fastow had created a company called LJM (which stands for Lea, Jeffrey, and Matthew—his wife and children). LJM was then primarily used for deals with Enron while Fastow was CEO. You need no business nor law degree to have the gut instinct that Fastow, owner/CEO of LJM and CFO of Enron, was playing some tricks. LJM became more or less a surrogate for Enron, providing the corporation whatever it needed to create the façade of success. Its role was to buy failing assets, sell assets, or act as a backboard for Enron’s assets in whatever way possible. Fastow didn’t stop with LJM, though. He created another outside entity, called Chewco, that provided a very similar role for the corporation. Chewco’s primary role was keeping Enron’s debt off its balance sheet as much as possible. These transactions were hedged by the Raptors: four entities contributing to the façade of transactions protecting the company from reporting huge losses.

Deals with these ‘outside entities’ owned by Enron executives added millions of dollars to the corporation’s earnings. These deals were also financed with Enron stock. By guaranteeing massive transactions with its own stock, Enron was creating a structure where a fall in stock prices could tank the entire company (spoiler alert: it did).

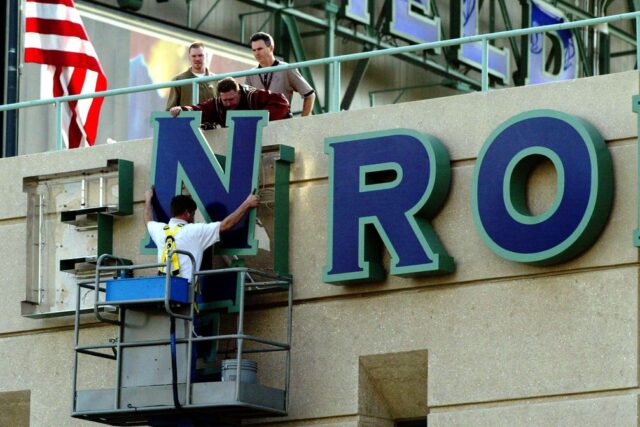

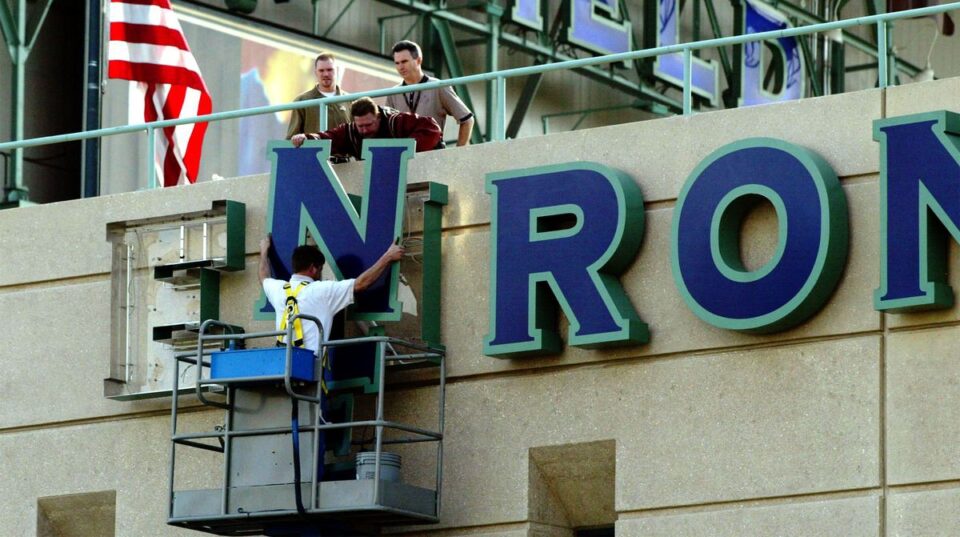

Image Source: Medium

Not only did Enron use stock to finance deals, employees were often paid with stock options, and pensions for retired employees were tied up in Enron stock. A stock option is essentially a promise to an employee that they can purchase stock at a set price, and then sell at the higher price when the value goes up (because, clearly, Enron stock would never go down). Payment in stock extended all the way up the chain, with executives making more from their stock sales than their salaries. Ken Lay, for example, made $19 million in salary and bonuses from 1998 until 2001. His stock profit? $217 million.

“When the financial advantages are so great to individual executives, and those financial advantages are tied to stock price, you’ll do anything to basically support that stock price.”

As Malcolm Salter of Harvard Business School told the Wall Street Journal, this compensation structure created a short-termism incentive for Enron executives: “When the financial advantages are so great to individual executives, and those financial advantages are tied to stock price, you’ll do anything to basically support that stock price.” By inflating the stock price, either through public statements, shell transactions (like those of Fastow’s), or other means of building their wall, Enron executives were able to drastically increase their pay.

Unfortunately, the opposite rang true for Enron employees. Once the curtain was lifted, Enron’s stock collapsed. Since most of their ‘profits’ were actually just fun with numbers, when the Wall Street Journal and other publications revealed Enron’s manipulation, the stock price spiraled. By this time, Fastow had been fired and Skilling had resigned, leaving only one musketeer: Ken Lay. Lay sold off his stock before the spiral while simultaneously encouraging employees and the public to hold onto theirs.

Some employees had lost faith in Enron and ignored Lay’s pleas to hold the stock. Instead, they attempted to sell theirs before its price kept falling. As it turns out, though, they weren’t able to do so. Instead, their accounts were locked during the spiral, surprisingly just because of bad luck: a scheduled changeover in administrators of the accounts. So instead, employees were left watching their life savings disappear for two weeks in October and November. By the time Enron filed for bankruptcy and laid pretty much everyone off (4,000 people lost their jobs), most were left with nothing. The Wall Street Journal provides some accounts of the damage:

“This was my life savings, my nest egg. We lived, ate, slept, and breathed Enron because we were owners of the company. My life savings is gone. In the end, I received a check for $20,418. That’s all that was left.”

Janice Farmer: “This was my life savings, my nest egg. We lived, ate, slept, and breathed Enron because we were owners of the company. My life savings is gone. In the end, I received a check for $20,418. That’s all that was left.”

Charles Prestwood: “I had all my savings, everything in Enron stock, I lost $1.3 million. It was from rags to riches back to rags.”

Mary Bain Pearson (a shareholder, not an employee): “I’m just a pebble in the stream, a little bitty shareholder. I didn’t lose millions. I didn’t even lose a billion, but what I did lose seems like a billion to me.”

This account of Enron’s collapse doesn’t even begin to provide the full story. Enron was also the primary cause of California’s blackouts, robbing people of both their financial stability and their basic quality of life, all in the name of gamesmanship. And, importantly, this didn’t happen in a vacuum. Enron was enabled by other companies, government officials, and its accounting firm, Arthur Andersen, all because of its promise of financial glory.

Jeff Skilling, our Mr. Macho hotshot CEO, pleaded guilty tp fraud and conspiracy. He was sentenced to 24 years (then reduced to 168 months) in prison and paid $42 million in restitution. Skilling is now back in the energy industry. Andy Fastow also pleaded guilty to fraud and conspiracy. He was sentenced to six years and ordered to turn over more than $20 million. Fastow is now a public speaker on business ethics (I know, right?). Ken Lay refused to plead out, swearing his innocence until the end. A federal jury, though, disagreed, finding him guilty of fraud (which carried a maximum sentence of 45 years). Lay died in 2006, before his sentencing or appeal.

Enron became a household name in ‘evil corporate executives,’ and, for that reason, serves as the backdrop for this column. Enron used financial manipulation, greed, and its ‘macho’ mentality to bend and cross any line it found—becoming the epitome of a corporate catastrophe.