(Over 70 H-2B workers protest in front of the White House in 2008 and demand that their employer, Signal International, be held accountable for fraud and human trafficking. The workers had paid between $10,000 and $20,000 in recruiting fees after being falsely promised good jobs and permanent residency, only to end up working in oil rigs in sub-human conditions. In 2015, 7 years after the protest, the workers won a $20 Million settlement, bankrupting Signal. Photo Credit: Jobs with Justice, 2008.)

But these improvements would come at a price. In return for the new protections and a fraught and lengthy path to permanent status, the FWMA would provide two big wins to its corporate sponsors. First, it would cap increases to the H-2A minimum wage for the next 10 years, making guest workers all the more attractive and cost-effective to employers. Second, and more troublingly, the bill would greatly expand and simplify the H-2A program, for example, creating a “one-stop” online portal to streamline the visa application process. With the Department of Labor failing to exercise adequate oversight over the program in its current size, FWMA opponents worry about its ability to enforce existing protections, let alone new ones, if the program were to expand even further. This is not to mention that the bill, by definition, does not cover the H-2B program.

A more viable solution to both H-2 programs, Economy Policy Institute (EPI) director Daniel Costa writes, would have to include legislative protections from employer retaliation and deportation, a minimum wage that matches, at least, the local average or median wage for the specific job, and true transparency in the recruitment process. Crucially, the changes must also provide interested H-2 workers with a clear path to citizenship, and untie their visas from a single employer, thus empowering them with the freedom to change jobs without losing their status. Only then could we begin to talk about a fair system.

Of course, statutory changes would be futile unless adequate resources are allocated towards their enforcement; and the Department of Labor (DoL) as it stands is far from having such resources. In a 2016 statement to Buzzfeed News, the Department pointed to its “finite resources” and its need to “be strategic” in its deployment to explain its limited success in stopping abuses. Indeed, according to a comparative analysis of the 2018 federal budget, the United States’ spending on immigration enforcement was an astounding 11 times greater than spending on labor standard enforcement. This data, Costa remarks, reveals that in the Land of the Free, “detaining, deporting, and prosecuting migrants, and keeping them from entering the country, is the top law enforcement priority […] —but protecting workers in the U.S. labor market and ensuring that their workplaces are safe and that they get paid for every cent they earn is barely an afterthought.” For any legislative reform to begin to be effective, this funding allocation would need to change, and the DoL’s mandate will need to be strengthened.

“Detaining, deporting, and prosecuting migrants, and keeping them from entering the country, is the top law enforcement priority […] —but protecting workers in the U.S. labor market and ensuring that their workplaces are safe and that they get paid for every cent they earn is barely an afterthought.”

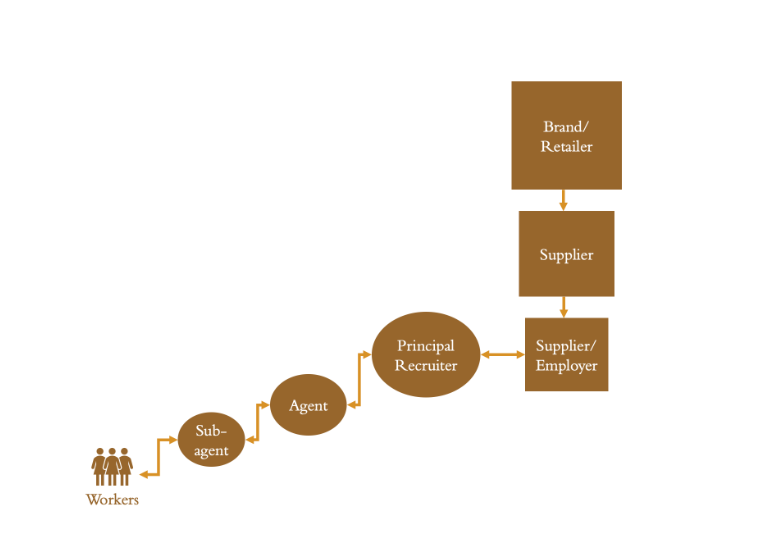

Finally, the essential step following enforcement is liability. Today, save for egregious cases, employers sanctioned for labor violations against H-2 workers have been required to pay nominal fines. This is not enough. In her landmark paper Regulating the Human Supply Chain, Professor Jennifer Gordon proposes a full-chain liability system that would include all the players in the value chains, starting with the recruiting agents operating in the workers’ origin countries, all the way to the large corporations at the top. Each player, she explains, would be “strictly liable” for all violations below it in the chain. This means that it would not matter if the corporations intended or knew about their suppliers’ or recruiters’ violations. If there is a violation, they will be required to pay a proportional fine, and, in the case of employers, will be permanently barred from participating in the H-2 program. Such a system would push firms up and down the chain to put structures in place to uncover and stop the abuse of workers, both by recruiting agencies on their way to the United States and by their employers once they arrive.

While controversial in the U.S., supply chain due diligence legislation is a growing trend in Europe, with laws in France, Germany, the Netherlands, and others, obliging large corporations to investigate, identify and mitigate risks of human rights abuses in their supply chains, at the risk of large civil penalties, and in some cases, criminal liability. These laws have the potential to shift the incentive structure, from encouraging worker abuse, to protecting against it. Given corporate power’s continued hold on Government, however, it is unlikely that such a proposal would see the light of day in the United States.

__________

On May 14th, 2008, a dozen H-2B workers at marine services company, Signal International, launched a hunger strike in protest of their sub-human working conditions. Two years prior, the workers had each taken steep loans and paid between $10,000 and $20,000 in recruiting fees to move from India to Mississippi, under the false promise of good jobs and permanent residency. Instead, they got temporary H-2B visas to clean oil rigs at below-market wages, were each forced to pay $1,050 in rent for tight trailers that cramped up to 24 workers each, and were threatened with deportation when they tried to organize.

In March 2012, the Department of Labor opened an investigation of L.T. West Inc., a crawfish processing company in Louisiana. The probe came ten months after the police arrested two of its H-2B employees, both women in their twenties, for leaving their homes and going on dates without their boss’s permission. The women, as well as their co-workers at the plant, had come to the United States from Mexico in search of a higher wage to support their families, only to have their passports confiscated, live in pest-infested trailers, and work up to 15 hours per day, sometimes for less than $4 the hour. Their supervisor, Craig West, would also sexually harass the female workers and call them his property. Some nights, he would invite his friends to their trailers.

On November 22nd, 2021, the Department of Justice announced the indictment of two dozen individuals who had participated in a “human smuggling and labor trafficking operation” in Georgia and subjected over 100 H-2A workers to abhorrent conditions. The workers, hailing from Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras, had been living in “cramped, unsanitary quarters and fenced work camps with little or no food, limited plumbing and without access to safe water,” and were forced, sometimes at gunpoint, to “dig onions with their bare hands” for as little as 20 cents the bucket. Some were continuously raped. Others were sold. Two died on the job.

The workers in the above examples came from different continents, and worked for different employers in different industries, states and decades, and yet, their experiences were highly similar. Far from being unique, their stories indicate a pattern of guestworker exploitation and abuse in an America that remains captured by corporate power and greed. Indeed, the one unique aspect of the stories above is that they received press coverage. And yet, despite public attention, the H-2 program remains unchanged. This, however, has not stopped workers like Daniel Castellanos, from fighting the fight.

__________

Looking back at his time in the United States, Daniel Castellanos realizes the impact he has had on the guest-worker movement, not just as a worker, but as an organizer as well. “Every time I get a new group of workers,” he says, “I [see] myself in them. There is a lot they didn’t know so they were afraid. Opening their eyes and making them see that they have rights is very satisfactory for me as a human being.” He continues. “I said this to my wife. I came for literally 10 months to the United States with this visa, and I [have been here for] more than 10 years. I think God sent me to do a job. And I am continuing to do the job.”