It was against this backdrop that Blockbuster Video arrived on the scene—with an unexpected origin story in the oil industry. In 1978, David Cook founded Cook Data Services Inc., which offered economic-analysis software for oil and gas companies. In each of its first five years, the company more than doubled its sales, peaking at $6.1 million in 1982. At the initial public offering for Cook Data in 1983, investors responded enthusiastically, and Cook had $8.4 million in the corporate treasury. But soon after the IPO, oil prices started to slide, and sales of Cook Data plummeted. Just a few months after the offering, stockholders filed a class-action suit charging that the company had made misleading statements about its earning prospects.

As Cook explained to Inc. in an article published in 1987, Cook Data was left in the “very delicate position of having been given all this money and then finding the industry we were going to invest in had gone away.” Cook centralized operations and cut 37% of their staff: “Emotionally, I was destroyed. These were people who had come from other jobs for a future at our company, and we were laying them off. Many of them had been friends, and none of them had done anything wrong.”

At this point, Cook knew he had to get out of the oil industry but didn’t know where to go. So in the spring of 1984, he hired a consultant to design a “strategic sieve” through which to run every possible enterprise. “We were looking for a fragmented market without dominant players, a business that could be set up on a local basis and easily replicated in other markets, and a business where we could throw up some competitive barriers.”

Video rentals fit the bill: It was an industry built from scratch by mom-and-pop proprietors, most of whom had about $30,000 to $50,000 in start-up capital to open a store with a few hundred tapes for the neighborhood. And home movie viewing was quickly becoming a national habit, with videotape rentals growing rapidly in the early and mid-1980s.

In 1985, Cook settled the stockholder suit against Cook Data Services Inc. by issuing shares of the company stock to plaintiffs, worth $862,000. The settlement precluded the stockholders from suing again in connection with the offering. After the settlement, Cook sold the company’s energy-software operation and was left with just four employees and $9.2 million in cash. “Overall, it was like somebody handing me $10 million and saying, ‘Here, develop a new business,’” Cook told Inc.

It was more than enough cash to explore the video rental business, and Cook had plenty of models when it came to conquering fragmented markets: Toys “R” Us, for example, had done it in toy retailing, and 7-Eleven in convenience stores. Initially, Cook had planned to join another video rental franchise called Video Works. But when Video Works owners refused to let Cook decorate with the blue-and-yellow design his wife had mocked up, Cook decided to open his own store instead. And that was the beginning of Blockbuster Video.

Cook planned to pour up to $700,000 in video superstores with massive inventory, applying his computer expertise to create a database of the stock and creating a $6 million distribution center that would allow new stores to pop up instantly. It was more capital, more inventory, than small operators could overcome.

Cook planned to pour up to $700,000 in video superstores with massive inventory, applying his computer expertise to create a database of the stock and creating a $6 million distribution center that would allow new stores to pop up instantly. It was more capital, more inventory, than small operators could overcome.

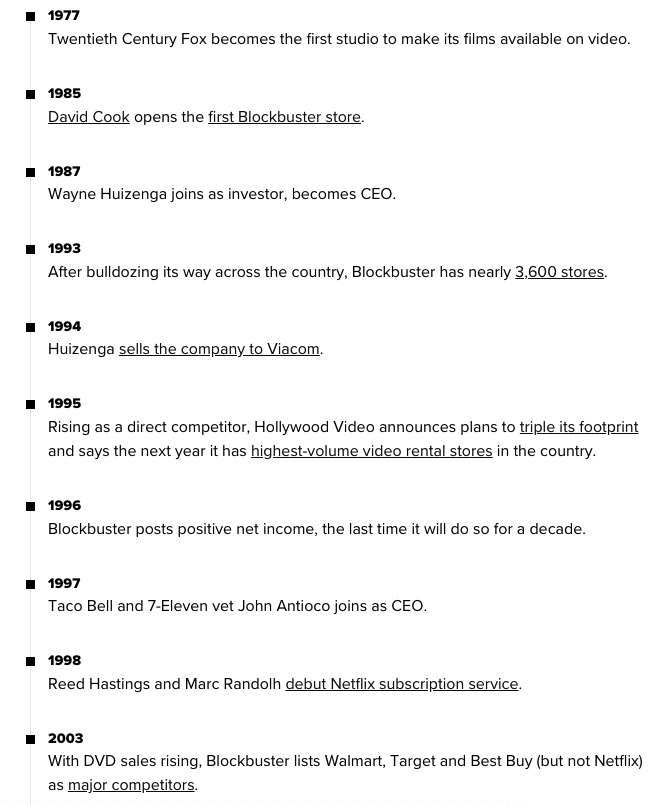

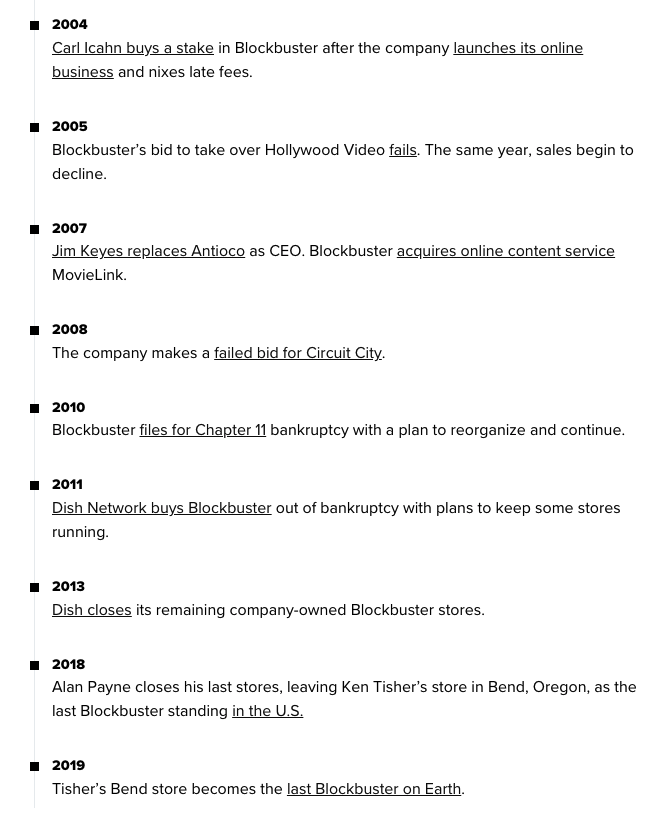

By the end of October 1985, the first prototype of a Blockbuster Video store was up and running in Dallas, and sales surpassed projections. In a year and a half, Blockbuster had opened 15 of its own stores, and its licensees had opened another 20 stores across the country, with sales of $6 million in the first quarter of 1987.

That same quarter, Cook relinquished control of Blockbuster to Wayne Huizenga, founder of Waste Management Inc., one of the largest waste-disposal companies in the United States, and AutoNation, which would also become the nation’s largest automotive dealer (Huizenga was also at some point an owner of the Miami Dolphins, the Florida Panthers, the Miami Marlins, the 43rd longest yacht in the world, and an exclusive golf club where he extended free privileges to friends who included actors Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones and GE Chairman Jack Welch).

Initially described by Cook as a “very friendly transition” in his interview with Inc., Huizenga and Cook soon had a professional disagreement over the expansion of the business. Huizenga wanted to borrow money to open more company-owned stores instead of franchising, while Cook worried about taking on more debt. Cook left, selling his shares for $12 million (he later estimated they would have eventually been worth around $300 million).

Cook would go on to develop the technology behind E-Z Pass and to found Zix Corp, which provided email encryption services, and was recently acquired by OpenText. But unlike Huizenga, Cook preferred to keep a low profile. As a 2003 CNN Money piece puts it: “[A]stoundingly, Cook has done all that without becoming a brand name himself. He could be pumping out self-serving books (à la Donald Trump) or posturing for public office (Trump again) or fronting his own reality TV series (must I repeat myself?). But that’s not him. ‘I’m sort of a recluse,’ says Cook, who lives in Dallas with his wife and two cats.”

Neither Cook nor Huizenga identified as big movie fans, even though Huizenga’s management ushered in even more aggressive growth with a plan to follow the McDonald’s expansion model to build Blockbuster Video into an American way of life. The strategy? Buy as many local and regional chains as possible while keeping centralized control over the look and feel of individual stores.

Neither Cook nor Huizenga identified as big movie fans, even though Huizenga’s management ushered in even more aggressive growth with a plan to follow the McDonald’s expansion model to build Blockbuster Video into an American way of life.

In his book, From Betamax to Blockbuster, Josh Greenberg notes that at some point, the company got so efficient at opening new stores that they could pack everything needed to open a store into a tractor-trailer, in the order it would be needed. By 1994—less than a decade after the first Blockbuster’s appearance—the company had nearly 3,600 locations generating close to half a billion in annual cash flow. It was larger than its next 375 competitors combined.

But Blockbuster’s rapid growth model wasn’t built with real competition in mind, and the arrival of other chains that started copying the Blockbuster model (like Hollywood Video), as well as new technology, posed a threat. Huizenga hired a team to research new ways to deliver movies. “We discussed it a lot and thought about buying a cable company,” Huizenga said in a 2010 interview with Time. “But there were so many ways it could go, and none of us wanted to get into an area where we had no expertise.” Having failed to conquer the tech risk, Huizenga sold Blockbuster in 1994 to Viacom for nearly $8 billion, as part of the drawn-out, infamous takeover of Paramount Pictures by Viacom. Blockbuster was essential to the Paramount acquisition: by absorbing the video-rental company, Sumner Redstone (chairman of Viacom and one of the real-life inspirations for HBO show Succession) was able to get his hands on Blockbuster’s $600 million in cash flow, allowing him to avoid taking on debt that would otherwise have compromised his position in the bidding war against QVC.

But after Viacom’s acquisition, Blockbuster struggled. Viacom attempted to turn the stores into outlets for its Paramount and MTV merchandise, selling toys, books, and clothing. Within a few years of Viacom’s acquisition, the company’s value fell by half. In 1997, Taco Bell president John Antioco came on board to turn things around. But perhaps telling is that Antioco’s brief Wikipedia bio has just one paragraph dedicated to his time at Blockbuster: “Antioco is best known for declining an offer, from Reed Hastings, to purchase Netflix for $50 million in 2000, while CEO of Blockbuster. He also refused a proposal from Netflix to run Blockbuster’s online presence.”

Antioco did manage to refocus the chain on movie rentals, and early in his tenure in the late ‘90s, he focused on hashing out revenue-sharing deals with major studios. Rather than paying upwards of $65 for a single tape upfront, Blockbuster agreed to pay its suppliers a portion, somewhere between 30% to 45% of its rental income, in exchange for a reduction in initial price to something around $8. Because studios wouldn’t stand to benefit from similar deals with independent video rental shops, this was yet another advantage Blockbuster had over mom and pops, and one more blow to the independent movie rental industry. Where an independent video store might be able to afford 3 or 4 copies of a new release, Blockbuster already had the capital to afford hundreds—and it was getting them more cheaply upfront.

However, Antioco didn’t strike the same deal for DVDs, and as studios turned to the DVD format, they also changed their pricing model; unlike VHS, DVDs were offered at prices average American consumers could afford. Revenue-sharing deals no longer gave Blockbuster a major advantage in the DVD space, and box retailers like Walmart and Best Buy quickly became some of Blockbuster’s biggest competitors, sometimes pricing movies even below wholesale costs, as loss leaders to drive traffic to their stores. When it was possible to purchase a DVD for $5, it no longer made as much sense to rent them from Blockbuster for $4.50.

Additionally, as a 2019 RetailDive feature by Ben Unglesbee points out, DVDs were also lighter and cheaper to send by mail, giving rise to Netflix’s initial mail-service business and allowing Redbox to pop up with a kiosk rental model. Overall, in a conversation with Unglesbee, former Blockbuster franchisee Alan Payne described the executive transition from Huizenga to Antioco as a “complete and total disaster.”

In a well-known piece of the lore, in early 2000, Blockbuster turned down the chance to buy Netflix for $50 million. Less well known is that the company turned down Netflix to then partner with Enron later that same year in an exclusive 20-year agreement to deliver a video-on-demand service. In classic Enron fashion, Enron estimated and booked over $100 million in profits from the deal before anything had materialized. When the deal ended up falling through (each party blamed the other), Enron didn’t change the valuation of its broadband business, and months later, the Enron scandal hit.

Former Blockbuster video rental shop in the UK, by Mark Anderson

Meanwhile, Blockbuster continued to falter, and in 2004, Viacom cut them loose. In a complicated buyback scheme, Blockbuster ended up borrowing $905 million, a debt that would come back to haunt them. That same year, the number of Blockbuster stores worldwide peaked at 9,000 stores, and in December 2004, Blockbuster attempted a hostile takeover of Hollywood Video, which had become its main US competitor. However, facing pressure from federal antitrust regulators, Blockbuster withdrew its nearly $1-billion bid, and Hollywood Video was acquired by a smaller competitor that has also since gone out of business.

In another attempt to compete with Netflix and other players, Blockbuster spent $400 million towards dropping late fees and launching an online-based DVD-by-mail business—but the move ate into both profits and inventory, as customers no longer had an incentive to return movies.

At this point, Carl Icahn took an interest in Blockbuster, bought a chunk of shares, and obtained representation on the board. Icahn had developed a reputation as a corporate raider in the 1980s after taking over Trans World Airlines, loading it with debt, and then selling off many of its best routes. Since then, he’d styled himself as an activist investor, buying shares and then campaigning for corporate changes at several companies.

Icahn, in a 2011 Harvard Business Review piece, called Blockbuster the “worst investment I ever made.” He thought that Blockbuster was overpaying Antioco, had burnt too much on its online business, and should never have cut late fees. Icahn’s influence ultimately sent Antioco packing.

Jim Keyes, the next and final Blockbuster CEO, made his name reviving 7-Eleven after its bankruptcy in the early ‘90s. Keyes’s original vision was to take over both RadioShack and Blockbuster and to combine the two in a sort of “technology-agnostic Apple Store,” Keyes told Unglesbee in RetailDive. But when Keyes found himself sitting in front of Icahn, Icahn convinced him to focus on Blockbuster first. The plan was to take Blockbuster private in a leveraged buyout and to refinance its $1 billion debt. But then it was 2007, and the financial crisis hit.

Many factors—debt acquired over acquisitions and changes in leadership, a market responding to increased risk-taking by banks and investors, poor managerial decisions—all contributed to the fall of Blockbuster.

Keyes realized that the company was in worse financial shape than he had known and attempted to switch focus to mail-order subscriptions by acquiring Movielink, a video-on-demand business. Unfortunately, the technology was clunky, and Blockbuster no longer had the means to acquire rights to the full library of movies.

“If the company didn’t have any debt, it probably would have survived a lot longer,” Grant Jordan, who covered Blockbuster as a debt analyst in the 2000s, told Unglesbee. The Last Blockbuster posits the same hypothesis—if Blockbuster hadn’t been saddled with so much debt, there’s a good chance it could have and would have competed with Netflix. Netflix’s existence didn’t make Blockbuster’s demise as much of an inevitability as most believe. Many factors—debt acquired over acquisitions and changes in leadership, a market responding to increased risk-taking by banks and investors, poor managerial decisions—all contributed to the fall of Blockbuster.

In 2010, Blockbuster filed for Chapter 11 and then defaulted on its bankruptcy loan after a poor holiday season, forcing it into a sale to satellite provider Dish Network. By 2013, Dish had closed the remaining Blockbusters that it operated, which only left a few franchisees that have since closed too. All except for one last Blockbuster in Bend, Oregon, opened by Ken and Debbie Tisher in 1992.

Timeline of Blockbuster’s rise and fall from Ben Unglesbee for RetailDive

![[F]law School Episode 5: The Business of Boredom](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Reed_1-640x427.jpg)