Unsurprisingly, this disruption of the landscape’s natural water flow has consequences. In California, as in most places governed by the short-sighted and unsustainable policies of capitalism, water has been falsely treated as an infinite resource. As water policy and infrastructure developed over the 19th and 20th centuries, there was little understanding of the impact that removing large quantities of water from rivers and aquifers would have on ecosystems, vulnerable communities, and long-term water supplies.

The negative consequences have become extremely apparent as climate change warms the planet and dries up previously reliable sources of water. Throughout the western U.S., drought has become less of an anomaly and more of a permanent state of being. It is felt in the explosion of fire season, as wildfires become larger and more frequent due to hotter temperatures and less rainfall moistening the earth. It is felt in the extremely low water levels in most reservoirs and the resulting water curtailments imposed in many communities during the summer. It is felt by the residents of rural Central Valley towns whose wells have gone dry and who don’t have the thousands of dollars it costs to dig a deeper well to reach the lowered water table. It is also felt in the inevitable negotiations over what little water is available, as farmers, tribes, municipalities, and environmentalists fight over how much water needs to stay in the rivers for the sake of the fish and wildlife that depend on it, and who gets the water that is allowed to be taken out. But these negotiations are not evenly balanced because agricultural corporations are an extremely powerful force, using their extensive capital to shape state and federal legislation, dominate the water utility districts in the Valley, and avoid any attempts to regulate their water usage.

Many communities are already feeling the impact of this reckless water management system, it’s now just a question of how many more will suffer and how little water will be left to future generations.

As the ongoing drought forces everyone into water conservation mode, those road-side signs along the I-5 highway demonstrate the continued conviction of farmers that they have an inherent right to water. And while it’s certainly true that many Central Valley farms will suffer without sufficient water, the agriculture industry is hiding a lot behind those signs. Most farms are no longer your typical small, mom-and-pop operations, but rather are large corporations with a lot of lobbying power and immense regulatory capture.

A lot of this activity is hidden behind trade associations, lobbying groups, ag-funded so-called ‘grassroots’ organizations, and water utility districts, making it very difficult to even quantify their outsized influence. And why does all of this matter, if at the end of the day the Central Valley’s farms are getting enough water to keep producing the crops that feed the nation? The answer is that there simply is not enough water to go around – so if the farms are taking more than their fair share, considering the little that is available, everyone else is not getting enough. Operating such large-scale, water-intensive agriculture across so many acres of the Central Valley – especially in the way that it’s currently done, with little movement towards adapting more water-efficient models – simply isn’t viable for much longer.

Many communities are already feeling the impact of this reckless water management system, it’s now just a question of how many more will suffer and how little water will be left to future generations. Remember, water is a limited resource and continuing to over-extract it at unsustainable rates has long-term consequences for the future of California’s water supply. Unfortunately, corporations operate under a capitalistic model where the long-term consequences and impact on surrounding communities are secondary to maximizing near-term financial gain for shareholders. Something is going to break in this system, it’s just a matter of when and how rich will the farmers get before it does.

Aerial view over the southern Central Valley. The contrast between the natural, arid landscape (on the right) and the irrigated farm fields (on the left) is stark. Credit: Brewbooks via Flickr.

In the town of Ducor, residents can’t seem to catch a break when it comes to having clean water in their homes. A small town in the southern Central Valley, there are around 600 residents who are primarily Latinx and low-income. Surrounded by farmland, the town experienced severe pesticide contamination of their water supply for decades. Families suffered from rashes and illnesses from using the contaminated water. Not having clean or reliable running water gets very expensive because you must constantly buy bottled water, and not just for drinking but for bathing, flushing toilets, and washing clothes and dishes too. In 2016, thanks to organizing by community members, they were finally able to get Tulare County to build them an expensive, but new, deeper, contaminant-free community well. In contrast to private domestic wells, which serve individual properties, community wells provide water for an entire town or neighborhood. They are preferable to domestic wells because the cost is spread across the community, which also allows them to be deeper and more resilient to drought. Like many of the Central Valley’s most neglected communities, Ducor is unincorporated, meaning that it is not part of a town, nor does it have its own municipal government, and therefore lacks municipal services, like a water utility company. Unincorporated towns are instead governed (and often neglected by) the county, in Ducor’s case, Tulare County.

In many unincorporated towns in California, residents either rely on private domestic wells or community wells – both of which are expensive to install and run a greater risk of drying up. Although many of the incorporated towns in the Central Valley do also rely on groundwater, they have the resources to build deeper, more resilient wells and the political power to protect them.

But just a few years later, Ducor’s new well is now at risk of becoming obsolete. Right across the street from it, a farm has drilled its own private well which is now making the community well dry up. The farm’s well is deeper and by pulling water from the surrounding aquifer at greater depths, it is drawing down the water table and rendering the community well too shallow. In large part this is happening because there is no regulatory process to determine where new wells can and cannot be drilled. So, when the farm decided to install their new well – which will likely only supply the farm – right next to Ducor’s well, there was no one to stop them. And since corporate farms aren’t inclined to worry about the wellbeing of their neighbors, there is little-to-no self-regulation to protect nearby wells.

Ducor’s problem is not only that the farm next door installed a deeper well. The underlying issue is that groundwater in California has been over pumped for decades, according to UCLA’s professor of environmental law James Salzman. Groundwater sits in the aquifer beneath the soil, like an underground reservoir. When it rains, that water seeps through the ground and recharges the aquifer. Wells on the other hand, pump the water out. Problems arise when the pumping rate is greater than the recharge rate – and the Central Valley surpassed this line decades ago.

The underlying issue is that groundwater in California has been over pumped for decades.

Up until 2014, groundwater was almost entirely unregulated in California, meaning wells were unmonitored and unregulated so landowners could pump as much as they wanted. The consequences of drastic over pumping are twofold. First, it causes the water table (the depth closest to the surface where there’s water) to drop, making it harder to reach and pump the groundwater. The worse the over pumping gets, the deeper one needs to drill a well for it to work, and since this has gotten worse over time, many older wells have been rendered defunct. Second, the dropping water table literally causes the land to sink, in a process called subsidence. In some parts of the Central Valley, the land surface has subsided almost 30ft.

Subsidence causes infrastructural problems which are expensive to repair, and at some point, the aquifer becomes so overdrawn that the damage is irreversible. It would take a long time, and require pumping to almost stop, for the aquifer to recharge itself to pre-agricultural levels. There’s debate as to whether the Central Valley’s main aquifers could ever fully return to their historical levels, in part because this drier climate means less rain and snowmelt are entering the system, and in part because the overextraction of groundwater has fundamentally altered the geology. Ducor is facing the double punch of a depleted aquifer and the localized issue of a deeper well extracting water away from a nearby shallower well.

Kyle Jones is the Policy and Legal Director at the Community Water Center, a community organization that works to end the Central Valley’s drinking water crisis. Jones says that when a well dries up, the only solution is to dig deeper. But installing a new well is expensive and even a small one can cost around $40,000. For the average resident in the communities dependent on well-water, that is an unobtainable sum of money. To put that amount in context, the median household income in Ducor is $27,000 as of the 2020 census.

When domestic wells dry up, the property value also dissipates – without water, there’s no value in the home.

When domestic wells dry up, the property value also dissipates – without water, there’s no value in the home. This means the resident can’t get a second mortgage or rely on their home’s equity, furthering their financial instability. On top of all that, they now don’t have access to water and must buy storage tanks to hold expensive, hauled-in water. By one estimate, over 1000 families in the Central Valley are now completely reliant on hauled water and at least another 800 domestic wells are predicted to go dry this year. The families that do manage to deepen their wells often find that it’s a short-term solution – sooner or later it will dry up too.

An East Porterville family was one of the first to receive water through a distribution system installed by Dept. of Water Resources in 2016 after many domestic wells went dry. Credit: California Department of Water Resources.

While the state will sometimes pay for a new well if a family’s income is low enough to qualify for state assistance or a town convinces them to, Jones says that the backlog in constructing these wells has left most people in limbo. The need for newer and deeper wells has recently exploded and there’s just not enough well drillers to go around. The drought and the ensuing restrictions on surface water have pushed farmers to draw more and more from groundwater to meet their needs. Corporate farms can afford to dig bigger and deeper, pumping even more water from the already depleted aquifer. This creates a cyclical problem: the new deep farm wells extract more water, leading to the drying up of shallower wells, leaving more communities in need of deeper wells again just to reach any water. When it comes to prioritizing which wells get drilled first, the large profit-generating agriculture companies are often first in line because their projects are bigger and more lucrative for drillers. The lower-cost, community and domestic wells have largely been left behind. In effect, the trees of wealthy farms have been prioritized over the survival of farmworker and Latinx communities.

In effect, the trees of wealthy farms have been prioritized over the survival of farmworker and Latinx communities.

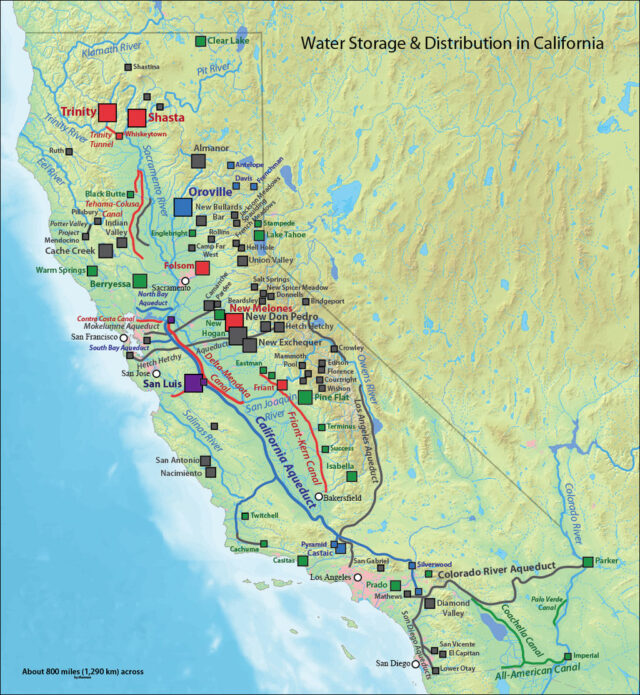

Historically, surface water has been the only regulated water source in California. Since the Central Valley is inherently arid, early on farmers primarily irrigated with well water. The introduction of the Central Valley Project, the system that distributes surface water across the state, induced farmers to switch to using mostly surface water. It relies on snow that falls in the Sierra Nevada mountains melting into various rivers (Sacramento, Stanislaus, Trinity, American and San Joaquin Rivers to name a few). Most of this water gets channeled into reservoirs and then into the Sacramento River before it empties into the Delta, where a series of aqueducts send it to the southern half of the state. This distribution is managed by either the Central Valley Project or the State Water Project; the former’s water is federally owned, and the latter is state owned. Both projects then distribute it to water districts, semi-public bodies that serve as water utilities for a given region. California has extreme variability in types of water districts – for starters, there are over 3,000 in the state – with some being governed by elected public officials and others by independent boards. Water districts then sell and distribute the federal and state water they’ve bought to their users.

In determining who gets what, California relies on a form of water rights allocation called prior appropriation. Put simply, it’s a “first come, first serve” system. Most real estate is tied to an associated water right, so owners are entitled to water in the order in which their property historically claimed it. Other entities can also have water rights, namely tribes, municipalities, and water districts. There are a few constraints, like a requirement to put it to “beneficial use” and to “use it or lose it,” but generally you can do whatever you want with your allotted water. Given the historical tendency to prioritize farmland, most of the Central Valley’s farms receive hefty quantities of water every year.

In a non-drought year, when water is plentiful, farms receive their allotted water provided by their local water district. This water is pretty cheap, so some farms will supplement it by buying additional water from other districts or farmers with surpluses. Depending on how much surface water they get, some farms will also pump groundwater. However, recent years have exposed the fragility of the Central Valley Project. California has been in its current drought since around 2011, with only brief periods of respite during the 11-year span. When water is in short supply, the “first come, first serve” system’s flaws are revealed. Firstly, the Central Valley Project is limited by how much snow and rainfall occurs in a given year. The Bureau of Reclamation must ensure that there’s enough water to go around and enough to stay in the rivers to protect the fish and wildlife populations. During such times, many users will have their apportionment of federal water cut. These curtailments are imposed in order from newest to oldest rights-holder, so those with senior water rights sometimes continue to receive far more water than makes sense.

Water districts are also part of this hierarchy and during droughts some districts get curtailed more than others. For example, in 2021 the LA Times reported that while some water districts got a mere 5% of their usual water allocation, others got enough water to supply all of Los Angeles for 4 years. The Imperial Irrigation District (IID), in the Imperial Valley, which lies outside the Central Valley but is similarly an agricultural hotspot subject to California’s arcane water laws, is another example of this contradiction. Salzman points out that because the IID has very senior water rights and is awash in Colorado River water, they are growing things like alfalfa and cotton – both extremely water intensive crops amid an extreme drought.

Map of the water storage and distribution systems in California. Squares indicate reservoirs (size of square correlates to capacity of reservoir), colored lines indicate canals and aqueducts, and light blue lines indicate rivers. Blue = State Water Project, Red = Central Valley Project, Purple = shared, Green = other federal infrastructure, Grey = state and private infrastructure. Credit: Shannon1 via Wikimedia Commons.

The curtailments of surface water delivered to farms leads to increased stress on the groundwater supply. When farmers don’t get enough water from their surface water rights, they turn to pumping well water. As groundwater extraction has historically been unregulated, landowners pump however much they want. The main limitation is the dropping water table which is pushing them to drill deeper wells – but this can only last so long.

At some point the water table will drop low enough that it becomes prohibitively expensive to drill deep enough to reach it.

At some point the water table will drop low enough that it becomes prohibitively expensive to drill deep enough to reach it. To stave off this fate, the state enacted the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) in 2014. The law requires the formation of localized Groundwater Sustainability Agencies which are mandated to create Groundwater Sustainability Plans and manage their local groundwater basins. So far, it has been a near failure and implementation has been delayed in almost all districts. The only ones benefitting from this failed attempt at regulation are the large growers with lots of land, who are just pumping, pumping, pumping while they still can, endangering the aquifer for everyone else.

Many argue that this system just doesn’t make sense anymore and something needs to change. The surface water rights were claimed as far back as the late 1800s, at a time when mostly only white, American men were legally entitled to own land. The result is an inherently racist system, where those whose ancestors were barred from acquiring land are the first to suffer today during water shortages. Jones points out that not only were people of color and women barred from securing water rights for generations, but they have also been kept out of wealthier communities that hold onto clean and secure water access. As a result, the Central Valley’s majority Latinx and farmworker communities don’t even get water from the state or federal government and are instead reliant on their own wells – which are proving insufficient as the agriculture industry depletes the aquifer at startling rates. Big farms almost always have a backup when water is restricted, but local communities who also rely on drinking water for their homes and schools are left empty-handed.

Big farms almost always have a backup when water is restricted, but local communities who also rely on drinking water for their homes and schools are left empty-handed.

It is no coincidence that farms of the Central Valley are continuing to operate at seemingly full capacity despite the state’s 11-year drought. These farms are large corporations with large amounts of capital and political power. The water districts, which are supposedly public entities, are completely dominated by members of the agriculture industry and spend millions of dollars every year lobbying in Sacramento and Washington, D.C. Together, they wield power over legislators to ensure that no laws get passed which might challenge their control or impose water conservation measures. When laws do make it past them, they are often toothless and ineffective – like SGMA. The end result is that the corporate farms keep taking water and earning profits, while 1 million Californians, like the residents of Ducor, go without a reliable source of water – and any attempts to rectify the problem or create a more sustainable system are hindered by the agriculture lobby. The agriculture industry has grown accustomed to getting all the water it wants, but decades of careless over-extraction combined with the effects of the drought have opened everyone’s eyes to see how unsustainable this is. The industry has resorted to manipulating all the levers of power to maintain the current, outdated system and even worse, to give themselves more water.

The industry has resorted to manipulating all the levers of power to maintain the current, outdated system and even worse, to give themselves more water.

What really frustrates advocates is that most Central Valley farms are incredibly inefficient when it comes to their water usage. Salzman says, “Central Valley farmers are in general, terrible at conservation.” The laws don’t incentivize farmers to enact more conservationist practices because of the “use it or lose it” principle of water law. If a farm were to put in place better irrigation canals on their property and reduce the amount of water lost during transport, they would end up needing less total water to irrigate the same fields. By needing less water, they run the risk of shrinking the amount of water they’re allocated, and no farmer wants that. Water is a scarce resource, so farmers would rather hoard water they don’t need right now in case they need it later. In the end, there’s little incentive to become more efficient today and risk losing your claim to some of your water tomorrow.

Fruit and nut trees are also a major issue when it comes to water conservation. Some “permanent” crops, like almond or pistachio trees and wine grapes, are very high value and many farms prioritize them for this reason. But they’re much less adaptable to drought than annual crops. In a dry year, with annual crops you can reduce your water needs by simply not planting in certain fields, a process known as fallowing. So, if you grow tomatoes, you can let a few fields fallow during a drought and the next year, when there’s more water available, simply resume planting. There’s certainly a loss of profits, but it doesn’t hurt the following year’s crop yields. If anything, fallowing is beneficial for farmland because it lets the soil rest and recoup its nutrients.

The corporate structure of these farms encourages maximizing profits in the near-term by planting lucrative tree crops, even if it means manipulating water policy into an unsustainable form that creates a long-term crisis.

In contrast, with trees, one dry year and they’re dead. If you have a grove of almond trees, not watering them for a season likely means they will die, and now you’ve lost the investment of the years it took for them to grow and the years it will take to restart the orchard. But as Salzman points out, corporate farms largely follow market trends and so when almonds and pistachios became a lucrative crop due to their popularity among consumers, farms prioritized planting them. It’s a risk worth taking for the farms that have enough wealth to know they can always buy water from someone else in a pinch and who have the political and regulatory power to ensure that they’ll keep getting enough water to irrigate their orchards. The corporate structure of these farms encourages maximizing profits in the near-term by planting lucrative tree crops, even if it means manipulating water policy into an unsustainable form that creates a long-term crisis.

![[F]law School Episode 14: Banking on Discrimination](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Babaian_FB3-640x427.jpg)