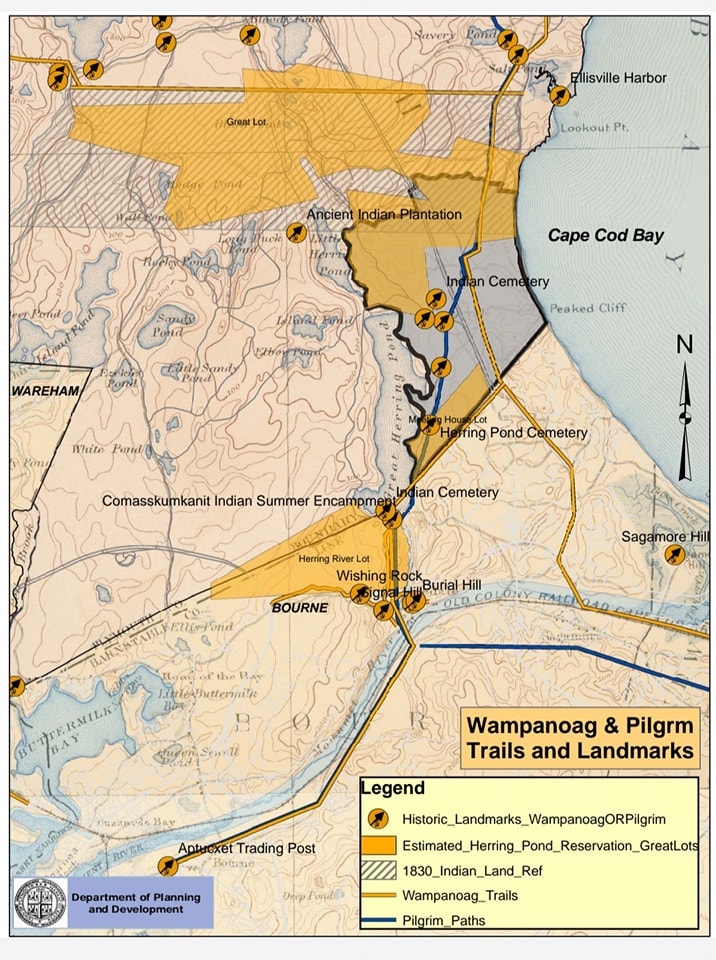

Map showing Wampanoag trails and historic landmarks.

Recently, she and the rest of the tribal council negotiated a land return with the Town of Plymouth. There, Plymouth returned a 6-acre parcel that contains a pond, pine woods, and an ancestral burial ground. Chairwoman Ferretti and the tribe plan to make the path that cuts through the woods more accessible and host educational and cultural events, like Pow Wows.

But many sacred sites remain on private property.

“This was my whole childhood–of my mom, taking me out and about in Massachusetts, and showing me different private property that was the location of very important, culturally significant sacred sites,” said Samantha Maltais.

Chairwoman Ferretti’s description of her tribe’s ancestral lands reinforced Maltais’ recollection. “The sacred sites are all through this region,” she explained. “A lot of these sites are Indian trails–the Megansestt Trail, the Agawam Trail–all of these trails had certain areas where there would be an encampment or there would be evidence found of aboriginal life.”

How do we navigate that, when people don’t even recognize that tribes exist here?”

For Maltais, this poses a problem: “How do we navigate that, when people don’t even recognize that tribes exist here?” she asked.

![scales - Logo for The [F]law](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/flaw_scale_divider.png)

Today, A.D. Makepeace occupies some of these ancestral lands. Founded by Abel D. Makepeace in 1854, A.D. Makepeace proclaims itself to be the largest private landowner in eastern Massachusetts. Historically, A.D. Makepeace farmed cranberries, eventually becoming the largest cranberry supplier for the popular juice brand Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc.

In fact, John Makepeace––a descendant of Abel D. Makepeace and CEO of A.D. Makepeace––co-founded Oceanspray in the 1930s. In 1995, John Makepeace’s grandson––Christopher Makepeace––helmed A.D. Makepeace and retained status as the largest shareholder for Oceanspray. The cultivation of cranberries on the ancestral lands of the Herring Pond Tribe enabled the Makepeace family to build and sustain generational wealth.

Then, in the 1990s, the cranberry market crashed. So Christopher Makepeace started to evaluate alternative avenues for the family business. Previously, Massachusetts had cornered the cranberry market and produced barrels that sold for $75–$80 per unit. But in 1996, Wisconsin cranberry growers entered the scene. The National Agriculture Statistics Reserve forecasted Wisconsin cranberry production to reach a “record high,” up 5% from 1995 and 15% from 1994. The result? The nation experienced a cranberry surplus, and profits for Massachusetts growers dropped to $16/barrel.

To restabilize profits from the company, Makepeace entered conversations with state and local authorities to obtain approval to develop 9500 acres of unfarmed land into residential and commercial buildings. These conversations launched A.D. Makepeace’s portfolio diversification into real estate development and management in the new millennium. Today, A.D. Makepeace owns and manages several properties, including the Rosewood Business Park, Rosewood Luxury Apartments, and several residential areas.

But demand for these commercial properties dropped again––and A.D. Makepeace changed gears. Jim Kane, the president and CEO of A.D. Makepeace, told Wareham Week journalist Chloe Shelford that a decade-long effort to market an additional site in the Rosewood Business Park received little interest. Additionally, he said, construction costs shot up and weakened the profitability of the real estate development projects. So plans for development of a technology park on Tihonet Road and for 1,856 residential units between Wareham, MA and Carver, MA were scrapped.

Instead, on March 15, 2021, Borrego Solar filed an Environmental Notification Form with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts that explained revised plans for A.D. Makepeace’s property: namely, replacing the proposed residential developments at 27 Charge Pond Road, 140 Tihonet Road, and 150 Tihonet Road with solar farms. This trajectory––A.D Makepeace’s transformation from a commercial cranberry grower to developer to solar project partner––showcases business acumen but also relentless pursuit of capital. Its land-use metamorphoses to serve its profit interests.

![scales - Logo for The [F]law](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/flaw_scale_divider.png)

A.D. Makepeace’s website attempts to reconcile its diverse, extractive land use with its brand as a local, environmentally-responsible corporation.

The visual features of the website accentuate A.D. Makepeace’s connection to nature. Light earth tones paint the homepage. The banner photo features an aerial shot of a cranberry bog, and the left side of the banner is stamped with A.D. Makepeace’s logo: a line-drawing of a cranberry branch on a yellow background, with the words “from nature” printed below. The pastoral palette, use of nature-based photography, and soft font choice all ground A.D. Makepeace in the local landscape.

Published news stories highlight its connection to the Plymouth and Wareham communities. The most recent post, published on November 28, 2022, reads: “ADM supports Old Colony YMCA.” The lede to the article celebrates a $137,000 donation that A.D. Makepeace made to the community organization. Other recent press releases include announcements about A.D. Makepeace’s donation of two all-terrain vehicles to the Carver Police Department, a $10,000 donation to the Wareham Library Foundation, and a $5,000 grant to the Wareham Tigers Cheer Team.

Taken together, the visual features and the presentation of local philanthropic efforts locate A.D. Makepeace as a homegrown enterprise that wields its influence to benefit both the community and the environment. But the website erases the complicated history of land ownership that underlies its property holdings on the Cape.

The page entitled cranberries on A.D. Makepeace’s website exemplifies the erasure. “Cranberries were first used by Native Americans, who discovered the berry’s versatility as a food, fabric dye, and healing agent,” the text on the page explains. The description goes on to discuss the methods that A.D. Makepeace cranberry growers today use to harvest cranberries, suggesting continuity between native traditional use and the modern agricultural practices employed by A.D. Makepeace.

But in reality, the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe rejects the extractive practices of colonizers and subsequent generations. “We have been at ground zero of colonial resource extraction for over 400 years,” Chairlady Harding-Ferretti said at the “Honoring the Land” rally. “Our fish, forests, and other wildlife in Plymouth, Cape Cod, were used to serve their interests as colonists.” Interests that include, for example, profiting off the cranberry cash-crop.

The real estate page advances the narrative of revisionist history. The description on the real estate webpage reads: “we purchased much of our land as many as 100 years ago. We are committed to development and agricultural practices that coexist in harmony with nature.” The page, notably, omits the complete history: that these lands belonged to the Wampanoag Nation for centuries before A.D. Makepeace acquired ownership.

Statements on its construction of solar farms further its narrative of its commitment to environmental, community, and social responsibility. Discussing another recent solar project constructed on A.D. Makepeace lands, Jim Kane said: “This is yet another example of our commitment to renewable energy.” He continued: “We see this project as a model in support of the Commonwealth’s climate change objectives.”

“This is yet another example of our commitment to renewable energy.” He continued: “We see this project as a model in support of the Commonwealth’s climate change objectives.”

A.D. Makepeace encapsulates the branding model used by many green capitalist corporations. Presenting as responsible environmental stewards, these firms engage with exploitative practices in the name of a clean-energy future. Meanwhile, the shareholders profit from the production of energy and associated green products––while continuing to inflict harm on ecosystems and perpetuating power dynamics rooted in colonialism.

![scales - Logo for The [F]law](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/flaw_scale_divider.png)

These dual and overlapping harms associated with A.D. Makepeace’s proposed solar farm developments in Wareham, MA, united a diverse coalition of activists.

Meg Sheehan, a local attorney and self-described environmentalist, represents another key actor in the campaign to stop the construction of solar projects on A.D. Makepeace property. After a stint as an Assistant Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the Environmental Protection Division, she joined the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority on the Boston Harbor clean up as a staff attorney.

During the 2010s, she became involved in the work to stop the construction of industrial-scale renewable energy projects on the Cape. “I started getting reports from people on the ground, in these communities, who have walked and hiked these trails for their entire lives,” she said during an interview this fall, explaining the genesis of her involvement. “They were sending me pictures and telling me about all of the clear-cutting of the forest and the sand-mining.”

In 2016, she represented Wareham resident Gene Lafond in a lawsuit against Renewable Energy Development Partners, a solar installation company that planned to build a solar panel next to his property. She lost on procedural grounds, and the project moved forward. But when A.D. Makepeace and Borrego Solar unmasked plans to build solar farms on Carver and Tihonet Roads, Sheehan entered the scene again.

She started to build a grassroots campaign against the developments, founding “Save the Pine Barrens”––statewide network of groups and individuals “taking action to protect our land and water and ensure a livable future for all life on earth.” The coalition centers its advocacy on protecting the rare ecological nature of the region. Wareham and Plymouth serve as the home to one of the last and largest remaining pine barren forests––called the “Atlantic Coastal Pine Barrens.”

![]()